Much remains a mystery about the planet’s melting ice sheets. NASA hopes autonomous robots can help

Polar ice sheets are losing billions of tons of mass every year, and meltwater is responsible for about a third of the global average rise in sea level since 1993

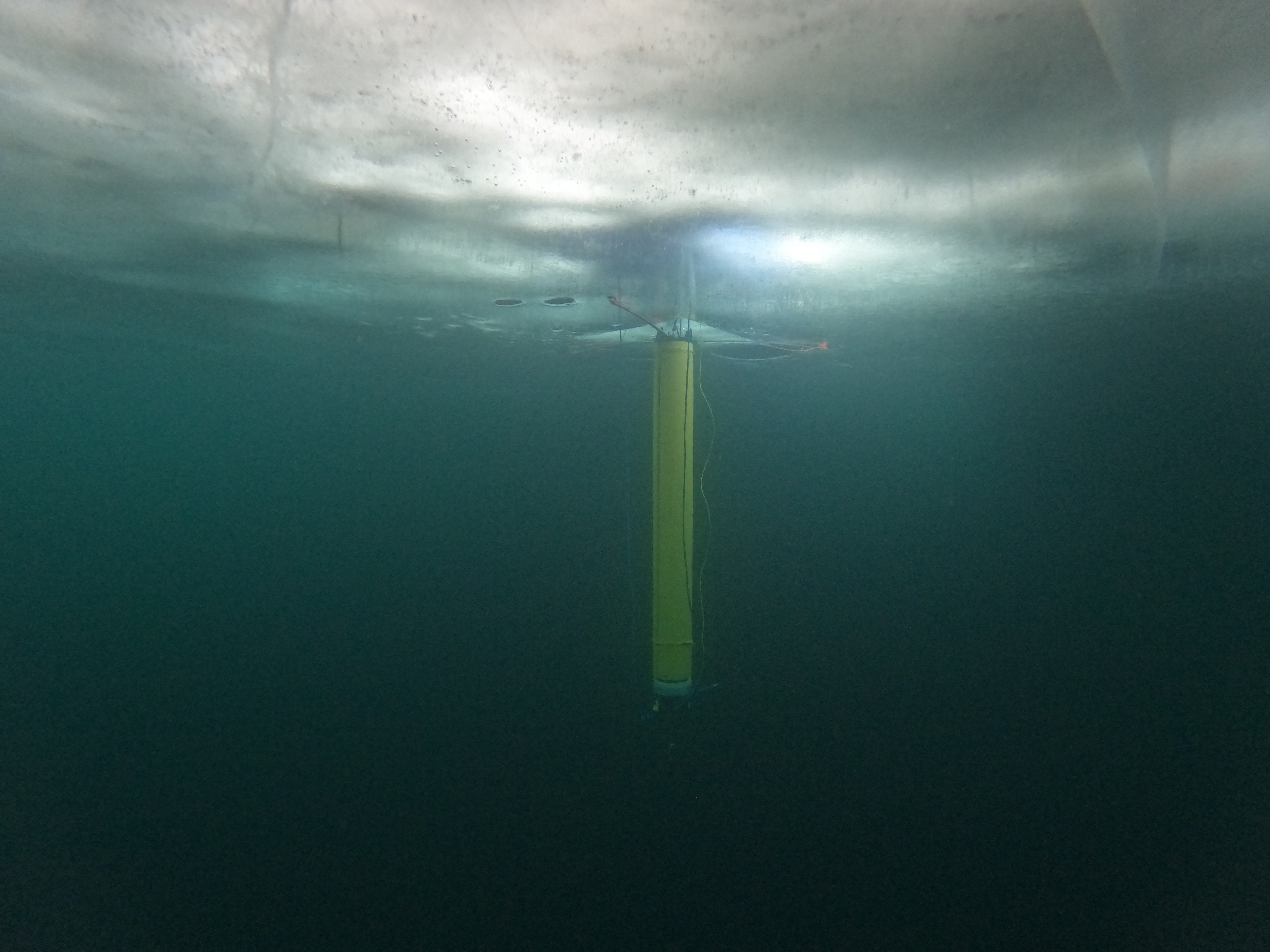

Just below the thick ice that covers Lake Superior, a three-legged, autonomous robot locked into position. In the frigid, dark water off Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, its spindly legs – extending out nearly ten feet when deployed – attached themselves to the icy crust.

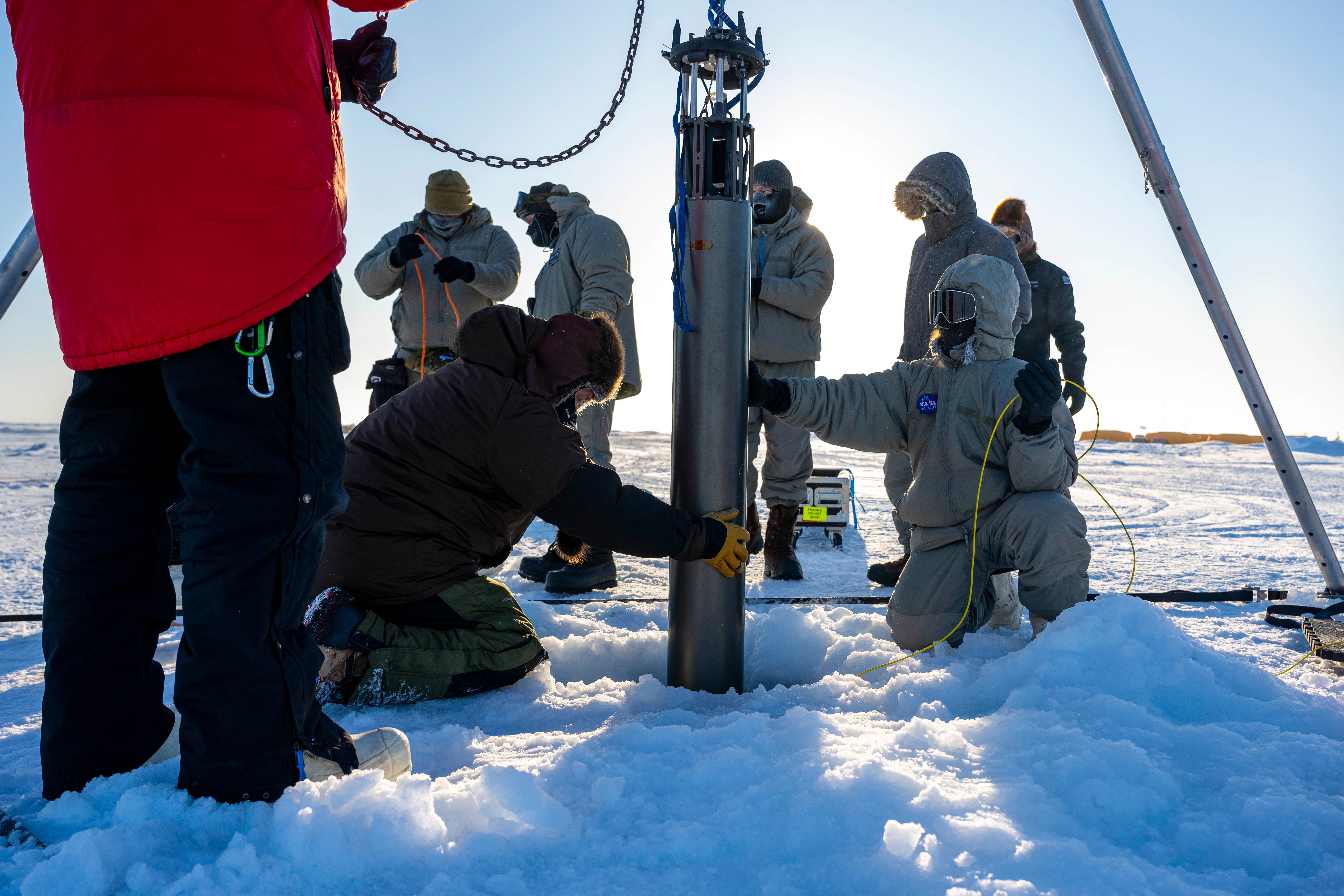

In newly-released photos this week, NASA shared the moment that the “Icenode” project, run by scientists at its Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), attached itself to the icy ceiling in winter 2022.

The project, running since 2019, is the agency’s answer to some urgent and difficult questions. While scientists have long known that the climate crisis is melting our polar ice sheets, much remains unknown about melt rates and timelines for potentially catastrophic tipping points.

Using this underwater robot, and eventually others, scientists aim to determine the rate of melting in ice shelves - the long, floating glaciers making up the outer edges of ice sheets - and improve computer models that predict sea level rise.

The Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets are losing billions of tons of mass every year, and meltwater is responsible for about a third of the global average rise in sea level since 1993.

Earlier this year, NASA brought the Icenode project tothe remote Beaufort Sea, just north of Alaska. The robot, about eight feet long and ten inches wide, was dropped through a drilled hole in the ice, into the sea. It can also be dropped into the sea from a boat.

The most recent test gave the engineers a chance to operate their prototype, although the robot was connected by a tether to the tripod that had lowered it through the hole.

The robot has the ability to float, and move itself higher or lower in the water.

From there, it will use novel software to determine the most ideal spot on the ice sheet to collect data. It might travel dozens of miles to reach its destination.

The robot will ride the sea’s current into the back of a cavity - a dangerous spot where the ice shelf meets the land and satellites can’t see - to attach itself to the shelf.

After that, the robot can rest - its next job is to sit and observe.

Its sensors measure how fast warm and salty ocean water circulates to melt the ice, and how colder and fresher meltwater sinks. The robot stays there for a year before detaching itself and using the same software to figure out how to reach a location where it can make satellite contact and transmit data back to Nasa.

In the future, Nasa hopes to deliver a fleet of the IceNode robots.

“These robots are a platform to bring science instruments to the hardest-to-reach locations on Earth,” Paul Glick, a JPL robotics engineer and IceNode’s principal investigator said. “It’s meant to be a safe, comparatively low-cost solution to a difficult problem.”

Glick told The Independent on Friday that more testing needs to be done and there’s currently no timeline for deployment “at scale.”

“But we’d ideally like it to be as soon as possible,” he said.

The Independent will be revealing its Climate100 List in September and hosting an event in New York, which can be attended online.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks