Is this $6.6 billion flying car startup the future of green transit, or just another rich guy fantasy?

Electric ‘flying cars’ could deliver low-carbon air travel — or another exclusive mode of transit that leaves the public behind

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When he was a child, JoeBen Bevirt, the founder of the flying electric taxi company Joby Aviation, had to take two city buses and walk 5 miles up a dirt road to get home from school. That home was a commune in the redwoods of Santa Cruz, California, which didn’t have electricity. It’s safe to say, then, that he has an acute understanding of how space, transportation, and resources combine to impact people’s lives.

Now, he’s at the helm of a company that could’ve changed his world and that of many more people if he accomplishes his ambitious goals. Founded in 2009, Joby is part of a group of red-hot startups putting billions of dollars into what was once a Jetsons-like dream: fully electric helicopters and flying cars that could radically alter the transportation system and make it less reliant on fossil fuels.

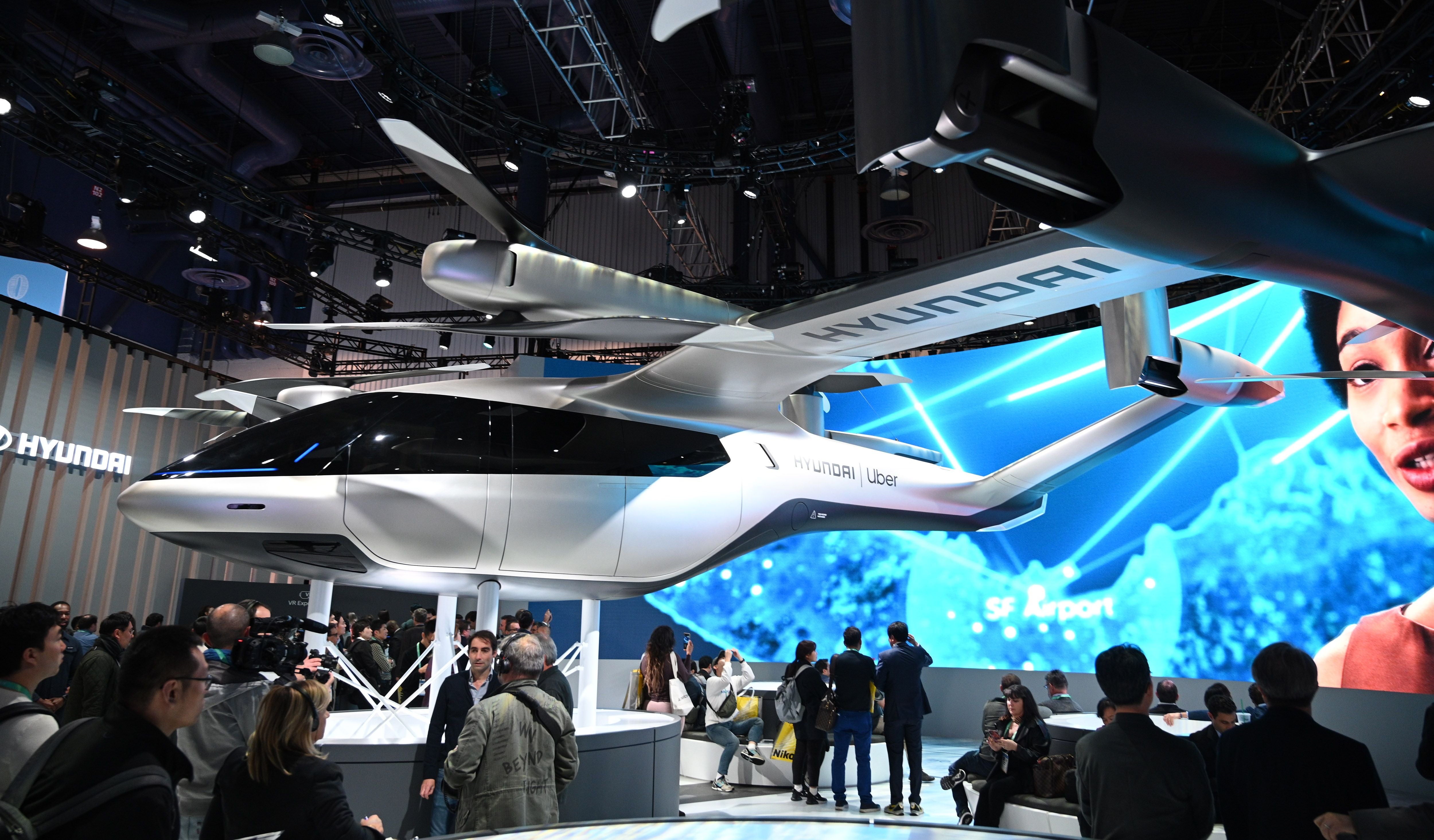

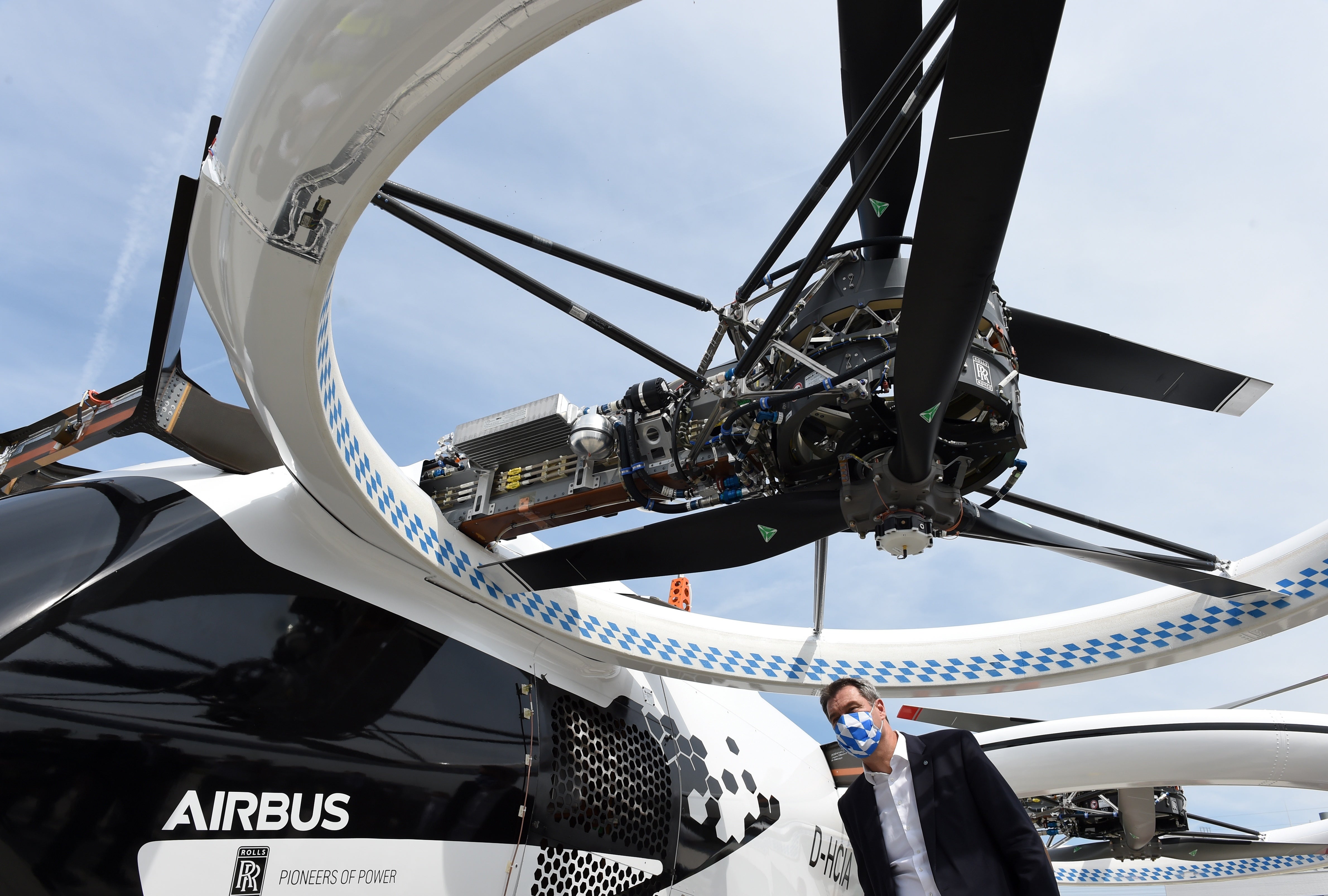

Though none of these companies — including firms like Archer, Kitty Hawk, Sunum, Lilium, and others — are yet operating commercially on a large scale in the United States, some have already gone public, wracking up billions in new capital. They’ve attracted high-profile investments from blue-chip companies like Toyota, Boeing, Lockheed, and Airbus. Demand for these craft, many of which are Osprey-style vertical takeoff-and-landing vehicles with electric power (eVTOLs), is projected to be $850 billion by 2040, according to Morgan Stanley. When Joby went public in August, Mr Bevirt became the industry’s first billionaire.

Boosters of eVTOL technology, as with many of the previous endeavours that were the Next Big Thing in Silicon Valley, speak of these aircraft with an evangelical zeal. They’re pitched as a utopian solution to the problems of urban gridlock and global climate disaster, all delivered in high sci-fi style.

“On the macro level, ever-growing cities create a growing mobility need from the citizens in those cities,” Fabien Nestmann, vice president of public affairs at Germany’s Volocopter, told the BBC. “That leads to a rethinking of the city, because building everything around the car doesn’t improve life quality.” Sebastian Thrun of Kitty Hawk told The New York Times, “Our dream is to free the world from traffic.” Joby’s tagline is to “save a billion people an hour, every day.”

These flying machines, with their sleek designs and panoply of rotors, are undoubtedly futuristic. But just what kind of future they herald is open to debate: one where we’ve managed to innovate new tech that solves global problems, or merely created another round of gadgets for the ultra-rich to avoid interacting with them.

Joby’s flagship craft, like many throughout the industry, is an aircraft that can take off vertically like a helicopter, then fly laterally like a plane. Its six propellers send it zipping across the sky at a top speed of about 200mph, faster than most commercial helicopters, and it has a range of about 150 miles, with enough room inside for four people plus a pilot.

Commercial air travel contributes between 3 and 4 per cent of US carbon emissions, and Joby hopes its electric craft, which create zero emissions while in use, will usher in a low carbon “age of electric aviation.” Until now, even the most carbon-conscious airlines could only go carbon-neutral by buying carbon offsets. Now, airlines like JetBlue and United are investing in electric planes, and flying car startups promise to make this technology accessible to regular people.

“Historically solving emissions in aviation has been a very big challenge. Electric aviation is really the first time there has been an opportunity for no tailpipe emissions,” Greg Bowles, Joby’s head of government relations, told The Independent. “That is critically important to the planet.”

Joby envisions offering Uber-style flights on demand by 2023, which they argue will help Americans get back some of the more than 4.5 billion hours they spend in traffic each year, while finding new ways to access under-used infrastructure like roofs and regional airports as landing pads.

More than that though, other electric aviation companies pitched their products as a deeper, society-wide innovation. They argue that these eVTOLs will open new pathways, flying routes longer than a traditional taxi but shorter than a plane, and radically change the world itself in the process. eVTOL maker Archer claims it could become “one of the most significant businesses in the world.” As Mr Bevirt once put it, technology like Joby’s copter would help people “work at their dream job while living where they want to live.”

“The opportunity of this technology introducing new degrees of freedom to solve mobility problems is remarkable,” Eric Allison, Joby’s head of product, said. “We’ve seen it happen a few times throughout the last 100 years, 150 years.”

The business and political elite have certainly bought into this vision. Toyota has invested $394 million in Joby, and Uber has put in more than $100 million. Joby’s backers include Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn, and the company partnered with federal agencies like NASA, and the Air Force, with which Joby has paid contracts. Other flying car startups and concepts have investments from one of Google’s founders and auto giants like Audi.

All of that begs the question, given that the most powerful institutions in America and beyond are betting on the promise of flying cars, and betting big: will these companies actually benefit the American public?

The first major question is price. Most of the flying car companies claim that, once they hit economies of scale, the price of a trip will be comparable to a luxury rideshare like Uber Black, or even cheaper.

It’s unclear, however, how companies like Joby and Volocopter will meet their goals of “democratising” aviation, as Mr Bowles of Joby put it. Even their hypothetical customer sounds more like a well-heeled venture capitalist or lobbyist than a workaday commuter.

“Well just think about, a couple years from now, when I want to have dinner, and I think, ‘It would be really nice to go out to dinner this weekend. Would you want to drive to the vineyard or something, maybe an hour, hour and a half?’” Mr Bowles said, imagining an ideal trip. “It’s a five-minute trip [in a Joby aircraft], do you guys want to go do that really quickly?’ Your 30-minute circle moves from 15 miles to 80 miles.” Another Joby executive described a hypothetical jaunt from Los Angeles to the desert resort destination of Palm Springs.

But taking a hard look at the economics of such flights starts to raise doubts about how cheap, mass electric flight could ever be a sustainable industry in a business sense. Joby has claimed that after its services roll out in a few cities, it could start bringing in $1bn in gross profits after two years. Right now, however, it could lose up to $150m a year, according to one of its investor presentations. Even ride-hailing giants with worldwide footprints like Uber don’t turn a profit, losing billions of dollars a year — and they’re not operating a vertically integrated helicopter fleet.

Joby declined to disclose how much its planes cost to build, but each one will be manned by a professional pilot, and smaller craft from its competitors costs hundreds of thousands of dollars each. In a few years, customers of flying cars may be able to call a flight like they call a Lyft, and indeed Joby purchased Uber’s flying taxi division Uber Elevate in 2020, but the economics of a shared car and a shared plane couldn’t be more different. Initial flights in a Geman Volocopter, which is now accepting reservations for 2022 trial trips, cost around $350.

Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy at the Center for American Progress (CAP), a liberal think tank, says he’s highly doubtful companies like Joby will ever be able to live up to their easy-access promise without loads of investor cash or public subsidies. He argues that electric buses, for example, are a far more efficient way to move people around a congested city than a small electric aircraft with a few seats, which shouldn’t really be thought of as public transportation at all.

“It’s affordable. It’s radically efficient. It’s clean. A 40ft bus can carry roughly 50 to 60 people in the space that’s normally taken up by two passenger cars being driven by a single person,” he said. “The benefit of flying cars is going to accrue to the users alone.”

For some, the bigger issue with how flying cars are portrayed, however, comes to environmental sustainability. These craft still require an enormous amount of carbon to manufacture, and people are likely to use them for non-essential trips at first, since comprehensive flying car infrastructure and coverage will take years to build out.

“There is less pollution at the point of use than a helicopter that has an internal combustion engine. That doesn’t make it sustainable,” Mr DeGood said. “The trips that people will take in the flying car are fundamentally additive. They are not substitutes.”

There’s also the matter of how often these craft will have customers inside in the first place. Flying cars use a disproportionate amount of energy taking off and landing, so longer trips are more resource efficient, yet those longer trips could also mean empty flying cars as they head back to the next group of waiting customers. Research suggests Uber and Lyft cars are empty nearly half the time.

“We’re not talking about taking a flying car or an eVTOL to take you from home to go to the cinema,” said Panagiotis Anastasopoulos, a professor of structural and environmental engineering at the State University of New York Buffalo, who has researched flying cars. “It would be far more reasonable to take it if you live, let’s say, in the suburbs to go 100 miles away to the airport.”

And if future developments were built with flying cars in mind, that could exacerbate the exclusion and waste inherent in suburban sprawl, one analysis from CAP found.

There are also reasons to be wary about the flying car industry’s claims, given that autonomous cars and ride-hailing companies, the previous Next Big Things in Silicon Valley-backed transit, have both failed to deliver on key promises. Some of the same executives from the major players in those previous industries — Uber, Google, Toyota — are now involved in the eVTOL world.

In the mid-2010s, companies like General Motors, Google, Toyota, and Honda predicted we would have millions of self-driving cars on the road by now, when in reality there are only a few sporadic pilot projects across the US and a handful of automakers like Tesla with some driverless features embedded.

“We’ve been talking about them for the last 20 years,” Professor Anastasopoulos said. “Still we haven’t seen significant progress in the actual penetration to the market.”

Major players in the space like Uber and Lyft have sold off or dropped out of their own self-driving car efforts, and a Pitchbook analysis suggests major automakers will need to pour tens of billions more dollars into development to ever make this technology reach the public. In the meantime, the industry has been dogged by ugly intellectual property lawsuits and accidents, such as when a self-driving Uber struck and killed a pedestrian in Arizona in 2018. The nascent flying car industry has seen its own share of IP lawsuits, reorganisations, and prototype crashes.

Ride-sharing, meanwhile, provides an even more direct comparison, since top flying car companies are explicitly emulating the Uber model or working with the company itself.

A major promise of ride-hailing companies was that they would reduce urban congestion, promote sustainable car-sharing, and drive the use of public transportation. Research suggests none of that has come to pass, and that companies like Uber and Lyft have actually made congestion worse while draining riders from public transportation, though both companies dispute this.

Over-promising and under-delivering on societal benefits is a hallmark of Silicon Valley culture, according to Stanford professor Fred Turner, author of From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism.

“It’s very much part of the water,” Mr Turner told The Wall Street Journal.

Joby Aviation recently purchased a large plot at a municipal airport in Marina, California, not far from the dunes of the Monterey Bay. The area once boasted a robust middle class economy, thanks to its proximity to Fort Ord, one of the largest military bases in the country, before the region began to struggle when the installation closed in 1994.

It’s a fitting home for a captivating industry, one that contains within it the promise of dazzling technical achievements and economic dynamism, as well as the potential to boom then bust. Flying car markers have figured out how to make jets once deemed impossible. Now they have the even more difficult task of living up to their own hype.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments