Pakistan election credibility already marred by internet blackout and slow count amid anxious wait for results

Analysis: With results slowly trickling in, analysts say the past two years of political turmoil show the Pakistani military’s grip on power is as tight as ever. Shweta Sharma reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As of Friday morning, we still do not know the results of Pakistan’s contentious general election – an unusually long delay in a country where preliminary indications of who has won normally emerge within a few hours of the close of polling booths.

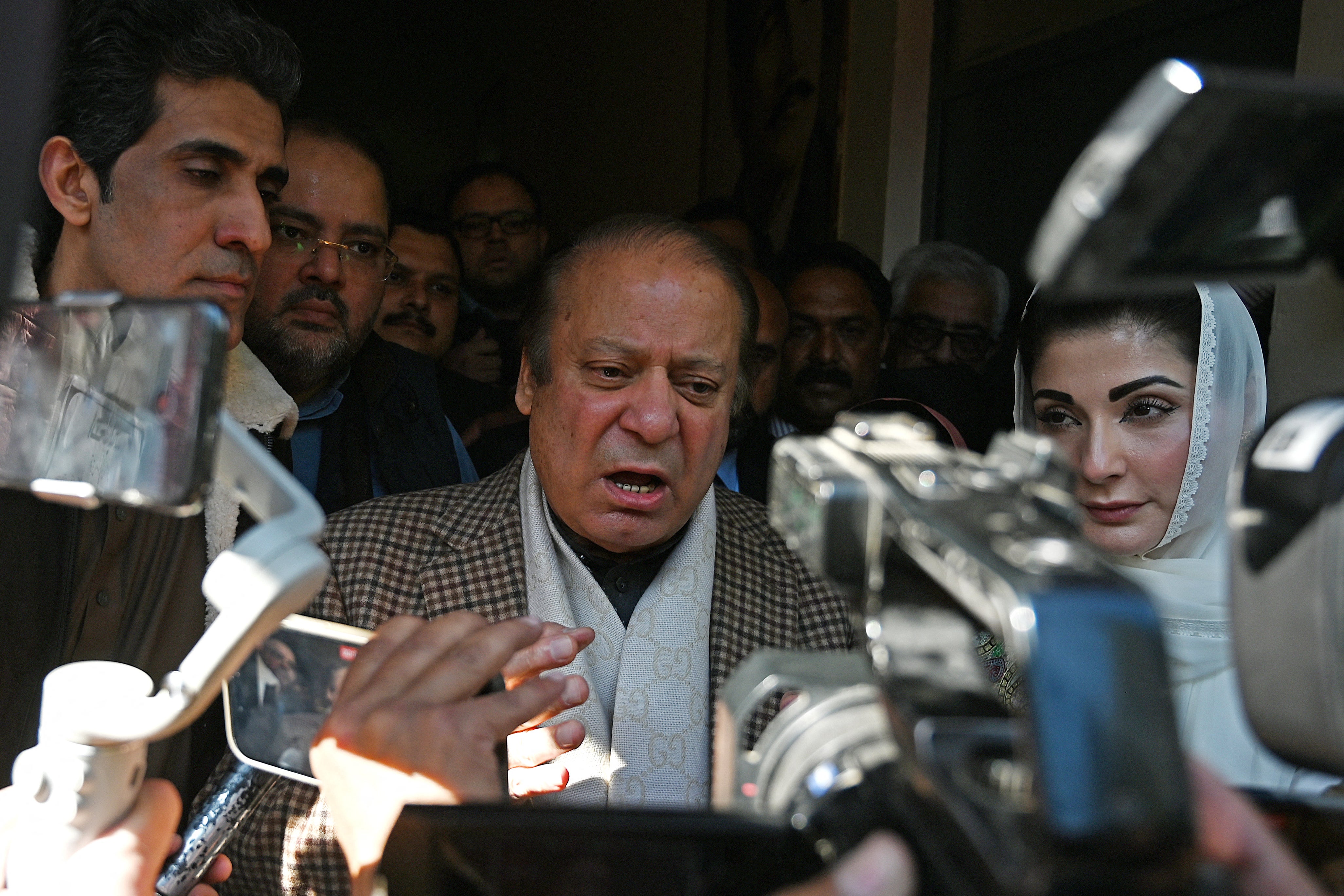

After the first few results were announced it was neck-and-neck between the pre-election favourites, Nawaz Sharif’s PML-(N) party, and a group of independents backed by former prime minister Imran Khan, with Bilawal Bhutto Zardari’s PPP party trailing in third.

But whoever ends up winning the election, the way it was conducted will guarantee recriminations over the validity of the result, and serves as a bleak reminder of the power still held by the country’s military establishment to try and interfere with its democratic processes.

Election day itself was significantly marred by unprecedented sweeping blackouts of mobile phone and internet services, long queues and reports of mismanagement at election booths, bloody violence in the form of deadly terrorist attacks against political offices and polling stations, and now delays in counting that have stretched well past 14 hours.

Even prior to the election, international observers including the UN had raised serious concerns about the treatment of Khan and his popular PTI opposition party, with the former prime minister jailed on a string of charges which he says are politically motivated, and thousands of party workers facing police action. In a final but significant blow, the party was banned from using its cricket bat election symbol on ballot papers, meaning its candidates had to contest as independents.

Analysts said that remarkably all this did not appear to have deterred voter enthusiasm, with anecdotal reports of large turnouts across the country. Official turnout figures have not yet been released.

The authorities said the suspension of internet and phone services across Pakistan was necessary in light of the threat of unrest and terror attacks, but it is likely to have disproportionately affected Khan’s PTI given the lists of its chosen independent candidates were largely available online. A lack of mobile internet also severely limited journalists’ ability to report on the election live, and of parties to coordinate their monitoring efforts.

“The mobile services suspension was a big blow to the credibility of the election,” Michael Kugelman, the Director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center, tells The Independent.

“It’s something that theoretically is illegal as multiple high courts have ruled it illegal and it will make it particularly difficult for voters to get more information about where to vote, and what their party of choice’s electoral symbol looks like.”

The internet suspension can hardly be claimed to have been an emergency or unexpected measure, given the country’s caretaker prime minister was asked about whether it would happen the day before the election. He and an aide off-camera told Sky News they had “no intention” to cut internet access on election day, hours before they did so.

“The elections have been anything but fair and credible,” columnist Mehr Tarar tells The Independent. “The situation here is bleak and the internet suspension is unprecedented as it did not happen during 2013 election when terrorism was at its peak.”

Tarar said she was nonetheless hopeful thanks to the apparently strong turnout as “they won’t really be able to do a lot of rigging in that case”.

Pakistan elections often involve flashpoints of violence for its people and political party workers. And this election has been no exception, with around 40 people killed across Wednesday and Thursday, including two bomb attacks that killed around 30 people in Balochistan province and nine deaths in a chain of bomb blasts and shootings at polling booths on election day.

Kugelman argues that the most significant developments occurred not on election day, but in the weeks leading up to it, during efforts to establish an electoral playing field that was not level.

“Whoever wins the election, and indeed it will likely be the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz of Nawaz Sharif, I think that it will be seen not necessarily as a reflection of the public mandate just because PTI enjoys significant levels of support and yet it was not able to mount a credible campaign just because it had been sidelined and weakened as a party,” he said.

But “most importantly it would be a victory for the military because it’s widely believed, and rightly so, that party is the preferred choice of the military to lead the next government,” he says.

Victory for Sharif would represent a remarkable turnaround since he was removed from office in 2017 due to a falling out with the military, subsequently paving the way for Khan, who is believed to have been supported by the military, to win elections a year later.

But their fortunes have since flipped, and now it is Khan who is behind the bars after a bitter split with the army.

Analysts say it appears improbable that any single party will secure an absolute majority, necessitating the incoming government to form a coalition led by the party with the highest number of seats.

If that can be achieved, it would be only the third instance of a democratic transition between civilian governments in Pakistan.

The military appears to have backed Sharif on the basis that, as a three-time former prime minister himself, he is arguably the only candidate with the experience and notoriety to counter Khan’s grassroots popularity.

“But that is going to backfire because they are not natural friends. Sharif and the army have sparred many times in the past and I don’t think that if Sharif comes back as minister again, he’s going to suddenly become more deferential and do whatever the military wants him to do,” says Kugelman.

“Imran Khan is popular,” notes Qamar Cheema, a political analyst in Pakistan. “The people are supporting him, the people want to vote for him. But at the same time, Nawaz Sharif is also very popular. He’s a three-time prime minister, he runs Punjab and his daughter Maryam Nawaz has been very active on the ground.”

As he cast his vote hours before polling ended on Thursday, Sharif appeared confident of winning not just the election, but an outright majority. “For God’s sake, don’t mention a coalition government,” he said after casting his vote in Lahore’s upscale Model Town neighbourhood.

He even suggested he was already thinking about which posts would go to his family members – including his younger brother and another former prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif.

“Once this election is over,” Sharif said, “we will sit down and decide who is PM (prime minister) and who is CM (chief minister)” of Punjab province, a job that is regarded as a stepping stone to becoming premier.

Given the assumed loyalties of the military to Sharif, it would take a massive and unquestionable public mandate for Khan to prevent PML-(N) from returning to power, analysts said.

“The deciding factor is which side the powerful military and its security agencies are on,” said Abbas Nasir, a columnist. “Only a huge turnout in favour of (Khan’s) PTI can change its fortunes.

“Economic challenges are so serious, grave, and the solutions so very painful that I am unsure how anyone who comes to power will steady the ship.”

Since he was ousted in a no-confidence vote in April 2022, Khan has been hit with more than 170 legal cases and a host of convictions with the longest jail term of up to 14 years.

But experts say Khan is not necessarily done yet, even if he loses out in this election.

“Pakistani politics has many stories of big comebacks and you’ve had so many political figures with nine lives and there have been 2nd and 3rd chances,” says Kugelman.

“I think that just because Khan is in jail now does not mean that he’s done. His desire and capacity to reconcile with the military and his recent messages from his jail cell suggest he’s in no mood for reconciliation, but that may change.”

“There could still be many more years of productive politics for him,” Kugelman adds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments