The art sleuths tracking down India’s stolen artefacts

Gerry Shih spoke to S Vijay Kumar about tracking down the thousands of items of art stolen from India and sold to museums on the grey market

On a cool night in February 2016, S Vijay Kumar, amateur art detective, got a hot tip from an informant.

A student in London reported that he had glimpsed a bronze statue in the backroom of an art gallery in Mayfair, partly visible behind a door that was left ajar. The tipster forwarded a smartphone photo: it was surreptitiously shot, but clear enough for Kumar to make out a 14th-century statue of the Hindu god Ram, its left arm gracefully bent skyward, the figure’s provenance almost certainly questionable.

So began one of the many cases that Kumar has taken on as part of a mission he has pursued for more than a decade: to track and recover the thousands of religious idols that have been looted from Indian temples and sold to museums and wealthy collectors via a flourishing international grey market.

Since 2008, Kumar has helped recover nearly 300 antiquities, from exquisite 10th-century bronzes of dancing Shivas to a hulking second-century BC Buddhist sculpture carved out of sandstone. He has reclaimed objects from art dealers in Amsterdam, private collectors in London, and institutions including the National Gallery of Australia and the Honolulu Museum of Art. He says he and Indian officials are working with the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum on returning a piece and have discussed with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to do the same for a half-dozen artefacts.

“Because of lax law enforcement, India was always considered fair game for trafficking antiquities compared to places like Italy,” says Kumar, who works in the shipping business by day but runs his side operation – his real passion – out of a tiny, rented office in Chennai, his hometown in southern India.

“The difference between India, Italy or Egypt,” he says, “is you’re stealing a god that somebody was literally worshipping the day before. These are living gods that we’re trying to bring home.”

India was one of more than 100 countries that ratified a 1970 United Nations convention that bans the trafficking of cultural heritage and requires the restitution of items that are provably stolen. That convention and other laws in various countries give Kumar the legal grounds to pursue items stolen from India since the 1970s, and they explain why he focuses less on large-scale looting that occurred during India’s colonial period.

When we hear about Indian cultural objects being returned by private and public collections, in fact Vijay’s often the one behind the scenes

Antiquities have been heavily trafficked in the modern era. The market is greased by the push-and-pull of thieves in poor villages who loot and sell their own communities’ prized idols – and by the continuous demand of wealthy collectors and museums half a world away.

In the 35 years before 2012, India recovered fewer than two dozen stolen pieces, according to a government audit. But the number of items recovered has soared in the past decade, thanks in part to Kumar’s volunteer group, called the India Pride Project, which scholars say is unique in the scale of its operation and in its track record.

“When we hear about Indian cultural objects being returned by private and public collections, in fact Vijay’s often the one behind the scenes,” says Emiline Smith, an expert at the University of Glasgow on art crime in south and southeast Asia. “The strength of his operation is that it’s secretive and it’s crowdsourced, so no one knows who his team really is. Is it one guy? Or is it a hundred?”

In reality, Kumar says, it’s about 40 people.

The India Pride Project has volunteers across the world who scour museums and galleries, collect and scan auction catalogues, and infiltrate private art showings and buy-and-sell groups on Facebook. “We’re lucky there are IT guys from India working in every city,” Kumar jokes.

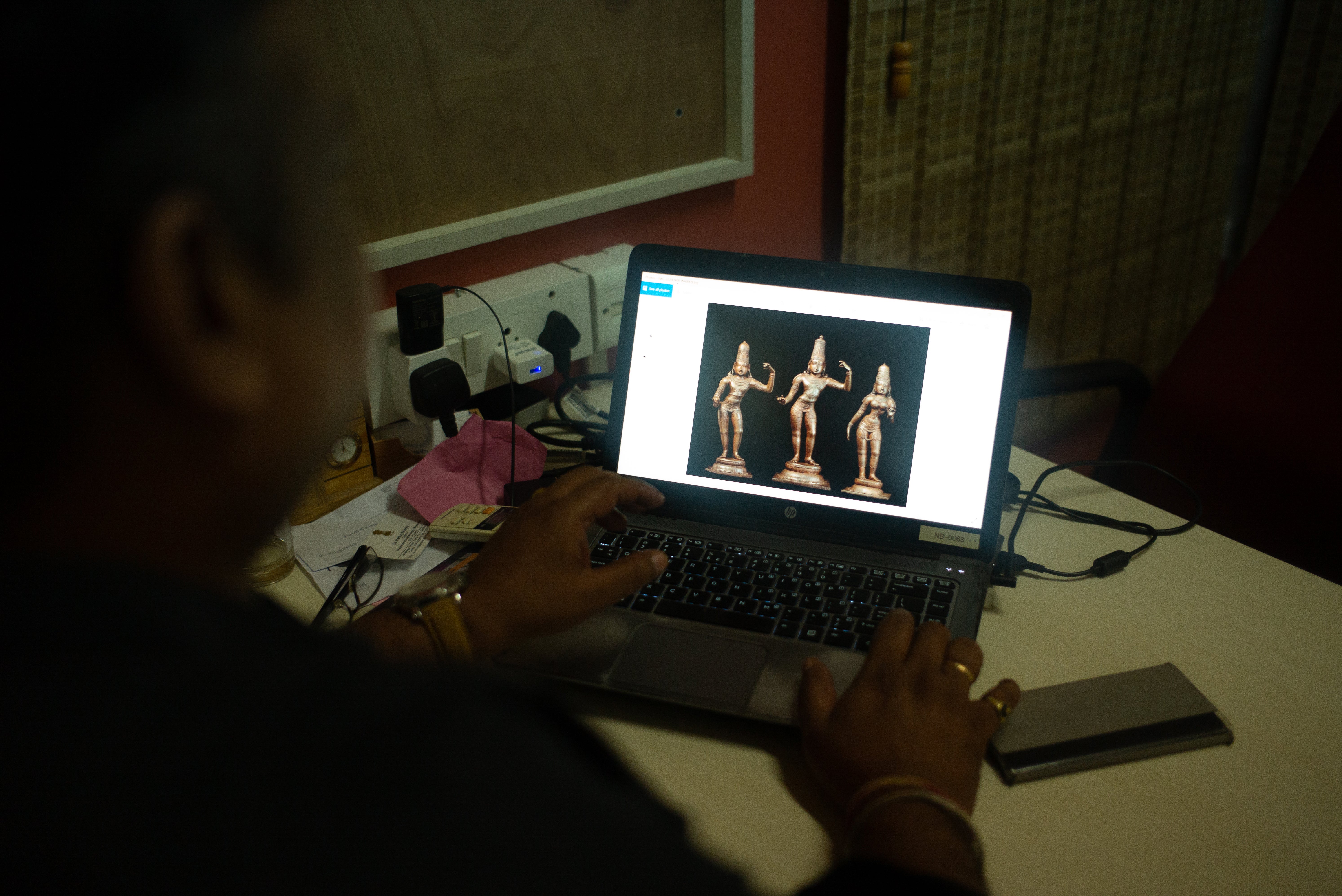

Whenever he receives new information about a piece of Indian art, whether it’s tucked in a dealer’s backroom or openly displayed in a museum, Kumar looks for distinguishing marks – metal casting imperfections, chipped bases, nicks and bruises. Then he runs them against his most prized tool, a database of about 10,000 pieces of temple art that he maintains on a laptop he carries everywhere. If there’s a match, and Kumar can prove that the item was initially stolen, he first informs law enforcement – most of the time.

In recent years, Kumar has become so active, and so well-known in south Asian art circles, that he is seen as both a blessing and a potential headache to some law enforcement officials.

Matthew Bogdanos, a veteran prosecutor who heads the antiquities trafficking unit in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office and has worked with Kumar on several cases, described him as an “extraordinarily valuable asset” who could also be overzealous with publicly shaming dealers and galleries.

“The bad guys definitely follow him,” Bogdanos says. “We’ve had investigations where the museum curator or auction house sits down and says, ‘Oh, this is coming from Vijay, right? We’ve already seen his tweet.’”

In the social media era, vigilantes like Kumar can “go public a little too fast”, Bogdanos says. “Information and evidence that might have been available disappears.”

As he was growing up in Tamil Nadu state, Kumar recalls, his grandmother nurtured an intense interest in Indian history after giving him a Tamil-language historical fiction series that narrated the imagined exploits of the Chola dynasty founder, Rajaraja the Great.

Kumar studied accounting in university, then launched into a career booking vessels for shipping companies in Singapore. But he spent most of his off-work hours in online forums, churning out essays on Indian antiquities. In 2006, he launched a blog called Poetry in Stone, likening it to a “dummy’s guide to temples”.

Soon, Kumar was accumulating a readership in India and abroad, and he would organise week-long tours around India to visit and document temple art. “I’m not a religious person,” he says. “I would show up just to look at the art but soon realised so much of it was missing. I said, ‘What’s going on?’”

Kumar had his first big break as an art sleuth in 2011, when he noticed that items being sold by the New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor had been documented, with photographs, in French studies of temples in Tamil Nadu in the 1950s. Kumar’s discovery, which was followed up by the Indian police, provided the final piece to a long-running investigation into Kapoor by Bogdanos’s office and the US Department of Homeland Security.

Kapoor was arrested on an Interpol warrant in 2011, accused of trafficking antiquities. Today, he is still on trial in India, while more than 1,000 pieces of south and southeast Asian art remain in the custody of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, which is seeking his extradition to the United States. Kapoor has pleaded not guilty.

Since 2011, Kumar has played a role in US authorities’ seizing a sandstone sculpture of the Jain spiritual figure Rishabhanatha from a Christie's auction. He has helped recover a Buddha statue looted from Nalanda, one of the oldest centres of Buddhist learning. In 2016, after his tipster told him about the bronze stashed in the London dealer’s backroom, Kumar launched into one of his most difficult cases.

He cracked it almost by happenstance. One day in 2018, Kumar was tracing the provenance of a figurine depicting the Hindu god Hanuman in a Singapore museum when he spotted in his database a 1956 photograph of the same statue taken by anthropologists in a Tamil Nadu village called Ananda Mangalam. Next to the Hanuman stood a Ram bronze that resembled the one stored in London, along with two other deities. They were part of a set, Kumar realised.

He tipped off the police, and investigators found local records showing villagers had indeed reported four statues pilfered from the same temple on 21 November 1978. Before long, police in Britain visited the London gallery, confirmed the match, and reached an agreement with the dealer to quietly surrender three out of the four pieces; the fourth idol remains in Singapore. The villagers welcomed the pieces back on 21 November, exactly 43 years after they disappeared.

That day, residents lit fireworks, carried the statues in a two-mile-long procession and immediately resumed worshipping them, recalled Madhavan Iyer, the temple’s head priest. “We celebrated grandly,” Iyer says. “But it’s not complete until the fourth deity returns. Kumar has promised it.”

These days, Kumar cannot sit for long before he is interrupted by messages and calls from his sprawling network. As Kumar plants himself in his cubbyhole, Madhu, a volunteer who addresses him as “boss,” calls for advice on whether a village temple should install surveillance cameras. Iyer wants a progress update on the sculpture in Singapore. Christopher Marinello, a London-based lawyer who specialises in recovering lost art, nudges Kumar over WhatsApp to discuss the matter of the dealer in Milan who wanted to return an ill-gotten bronze – quietly. Oh, Marinello adds, he had also tracked down another case in Brussels.

When he isn’t distracted by calls, Kumar scrolls through his laptop. There are ongoing cases and cracked cases. There are photos of bronzes and sandstone sculptures filed in folders upon folders. There are blurry photos sent in from tipsters who had attended private art sales in New York, showing women in black dresses and men in polo shirts clutching their wine glasses, beaming next to centuries-old objects of worship.

Kumar rubs his eyes in disbelief, or exhaustion.

For all his efforts, he says, antiquities trafficking is so pervasive that in absolute terms, he is not recovering even a significant fraction.

“But finding one out of 100 can still be a deterrent,” he says. “It’s akin to wildlife: when the buying stops, the looting stops.”

The Washington Post’s Kavitha Muralidharan contributed to this report.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks