Their homes were marked with black crosses. Now Muslims are leaving this Himalayan town in fear for their lives

As Muslims abandon their homes and jobs in a mass exodus, two idyllic Himalayan towns are in the grip of unprecedented religious tension, reports Namita Singh from Uttarakhand, India

When angry marchers filed past their Himalayan home, Naaz and her husband Irfan* were among the Muslims cowering in a back room, braced for violence.

Naaz sent Irfan and their children inside and readied herself to guard the front door should the mob try to barge in. When the protests had gone, they emerged to find their family business – a shop selling quilts and cushions, and one of the few Muslim properties in this corner of Uttarakhand – marked with a black “X”.

Ifran says the cross was daubed by young men during the 3 June procession, organised in the town of Barkot by a right-wing group in protest over the abduction of a local Hindu girl.

It branded him and his family as a potential target during religious tensions which has sent shockwaves through the region and prompted a number of Muslim families to flee.

“When the procession went past our house, we were just worried about if something unforeseen happens, or what if it rolls into something more than procession,” Irfan tells The Independent.

“There was a lot of noise,” says Naaz. “I was cooking in the kitchen when that happened. I screamed seeing the scale of the procession.

“I told my husband and children to sit in the inner room. I said I would stay in the outer room, next to the main gate. I don’t care if I die, in case the protesters barge into our house. But I was very scared for their safety.”

There were faces in the procession that Irfan recognised. “When I saw the mob through the window, it hit me terribly hard that the people... the friends with whom we spent time were now marking our homes, vandalising the shop. There was definitely a feeling of dismay.”

Irfan, rarely seen anywhere except his shop on a typical weekday, is now spending his days at home out of fear. He and his wife are facing the impossible decision: whether to stay, or pack up 40 years of their lives in Barkot and move elsewhere for their safety.

Irfan is not the only Muslim faced with this life-altering decision. Tension between the two religious communities began following the abduction of an underage girl by two men on 26 May in Purola, another hill town 12km from Barkot. Police took swift action and arrested two suspects, Ubed Khan and Jitendra Saini, filing charges under India’s stringent Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (Pocso) Act.

The aftermath of the incident has seen growing incidents of Islamophobia, with locals directing their outrage against resident Muslims.

Several right-wing groups, including the prominent Hindu organisation Vishwa Hindu Parishad, labelled the abduction a case of “love jihad” – a right-wing, Islamophobic conspiracy theory that claims Muslim fundamentalists are plotting to convert Hindu and Christian women to Islam through trickery or even forced marriage.

This is despite the girl’s family saying the incident should not be seen through a religious lens. “There were attempts from the first hour to make this a communal issue. Right-wing activists even prepared a police complaint for us on their own, but the police didn’t accept it,” the girl’s uncle, who was not identified due to legal reasons, told the Hindustan Times.

“It was never a love jihad case, but a regular crime. The judiciary will now decide.”

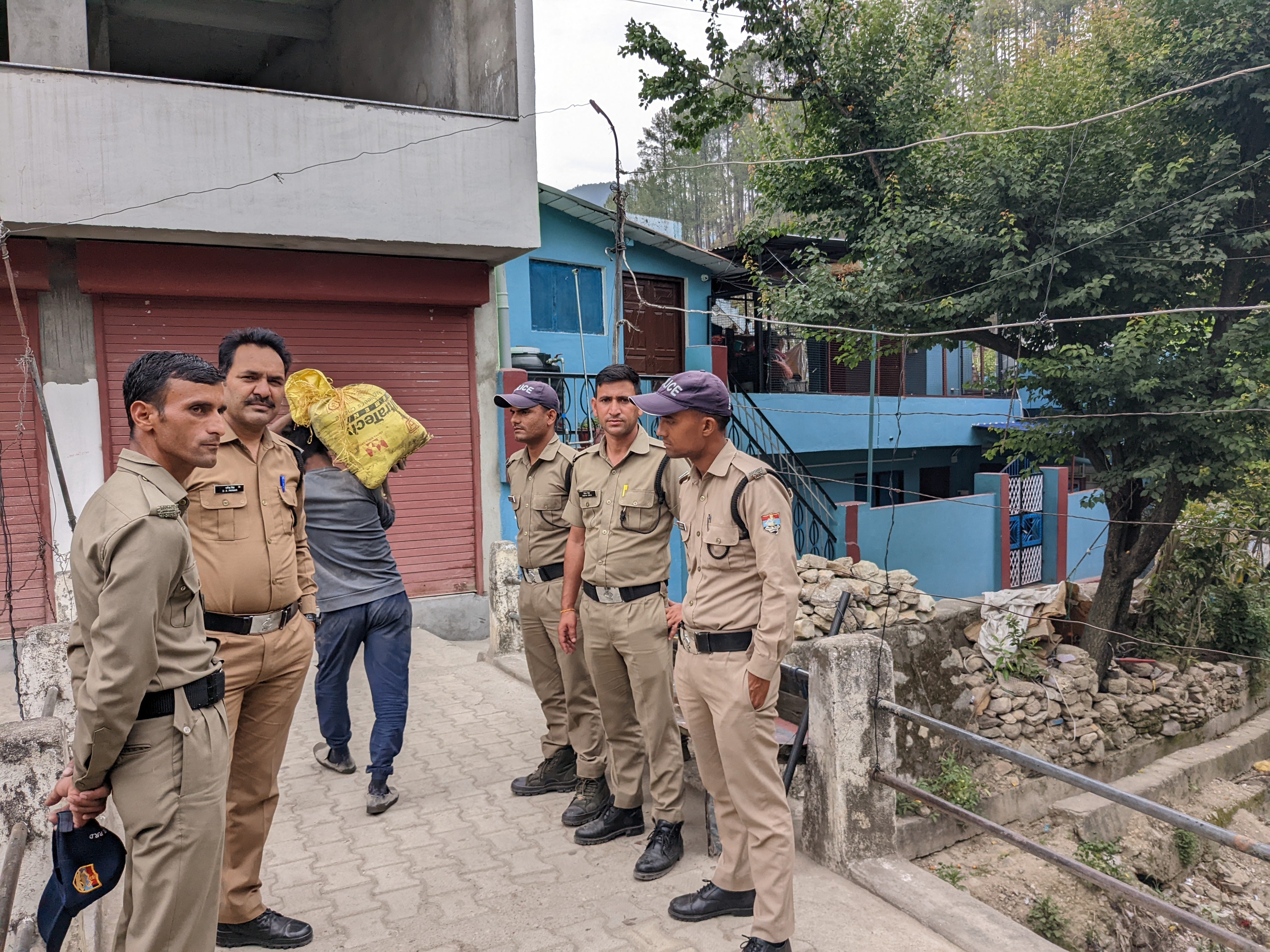

The incident has been followed by a series of protests and processions in both Purola and Barkot. A heavy police presence was visible on the streets in both towns when visited by The Independent last week.

A statement by Uttarakhand’s chief minister, Pushkar Singh Dhami, has done little to calm the situation. “People of different faiths co-exist peacefully in Uttarakhand but things like love jihad will not be tolerated,” said the politician after a 9 June meeting with senior police officers.

“Crimes like these were being committed as part of a conspiracy,” he claimed. “But people are coming out openly against them now. Awareness about love jihad is growing. That is why more such incidents have come to the fore over the past two-three months. One reason for this is the introduction of a severe anti-conversion law.

“Instructions have been given to the police to deal sternly with the guilty in love jihad cases. They have also been asked to conduct verification drives from time to time to look into the antecedents of people coming from outside and settling here,” he added.

Prior to this, Dhami declared that illegal encroachments in the name of “land jihad” would not be tolerated.

Irfan says his landlord is now being coerced into asking him to leave.

“There has been pressure on our landlord to ensure that we move out of the house. We have not been told anything directly. We heard through others that a few people went to our landlord, pressuring him into ensuring that we leave this house.”

“We don’t have anywhere to go. We do not know what to do,” he says.

A 42-year-old Muslim neighbour, who requested anonymity, also had a cross daubed on the shutter of his clothing shop and his name covered by black paint. Since the incident, income from his clothes shop has dropped to zero. Irfan says this was true for him as well, with customers staying away from the marked shops.

In Purola, posters bearing ominous messages such as “Love Jihadis are warned that you vacate the shop before the mahapanchayat on 15 June 2023” appeared, referring to a grand assembly of people from various villages. “If you do not do this, then you will have to just await the outcome.”

The open threat ahead of the mahapanchayat assembly is seen as being the primary trigger for an exodus of Muslim families from the town. In a town with a population of roughly 20,000 individuals, there were only 35 to 40 Muslim families before these tensions began – comprising 0.1 per cent of the total population – council chair Hari Mohan Singh Negi says.

Of these, at least 12 families shuttered their shops and fled the town permanently, said locals, while not a single Muslim family stayed in the town on 15 June itself due to fear of violence, a senior police inspector tells The Independent.

Among those fleeing Purola is Mohammad Zahid, himself a member of the ruling BJP. He served as district president of the BJP’s minorities group for the area. “I felt scared for my family, so we left,” he told the Quint. “If a BJP post holder is feeling threatened, who is safe then?

“There was also a Hindu boy [arrested for the abduction],” he said. “If you want us to leave, they should as well. Treat all criminals the same.”

Due to the fear of violence, all shops in both towns were closed last week, while a heavy police deployment of up to 200 officers provided protection to shops and residences belonging to Muslims.

The mahapanchayat was cancelled due to the imposition of strict security measures, including an order limiting public assembly in the region, effective until Monday. It did not prevent Hindu right-wing groups from gathering and attempting to push past the police barricades.

The only road connecting Purola to Barkot was blocked, with protesters demanding they be allowed to continue. “We are here to wake the Hindus for the mahapanchayat,” saffron-clad Mahant Keshavgiri Maharaj tells The Independent, while he and his supporters continue to blockade the road for three hours, before being taken away by the police.

“By stopping us, the administration is trying to suppress our voice,” he says. “If we were allowed to continue with the protest, we would have demanded all the Hindus to unite against love jihad and land jihad.”

Angry at being stopped by the police, another protester, Manmohan Rawat, says: “We are Hindus. We are the majority, so why are they being given so much protection.

“If they are being given such importance despite being in small numbers, imagine what will happen if their population grows further.”

Mohammad Ashraf, from Purola, expressed his disappointment with the escalating tensions and the discrimination faced by the Muslim community. “One person is making the mistake, but the entire community is being blamed. The person who committed the crime is being punished. Then why are we the casualty?" he asks.

“Tell me the section of the law under which a person of one community will make a mistake and all the people belonging to that community are forced to migrate. Is there any such law?” he asks.

“It would not have spiralled into such a big thing if the administration had taken cognisance of the matter right at the beginning,” says Ashraf.

“I have been living here since 1978. I was born here. My children were also born here. My whole life is here. My home is here, my work is here. You tell me, where should I go?”

(*Names changed to protect identities)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks