The inter-tribe couples trying to survive as their communities are ripped apart

In India’s Manipur relationships between Kukis and Meiteis were not that uncommon before violence erupted, bringing the state to the brink of civil war. Namita Singh meets families whose lives have been destroyed by the crisis

Joshua Hangsing was downstairs when he heard his seven-year-old son cry out in pain. The family were living in an army relief camp after fleeing their home as India’s Manipur state descended into a bloody tribal conflict.

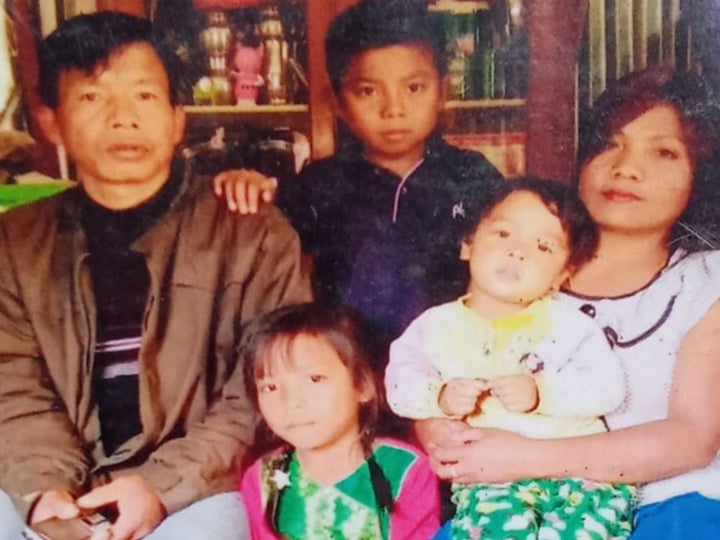

A 55-year-old from the Kuki tribal community, Hangsing didn’t stay in his Kuki-dominated village in Kangpokpi after the violence broke out because he needed to protect his wife – a Meitei woman named Meena.

Their story of love across tribal lines is rare but not unheard of in a state where the two communities lived mostly in harmony until around four months ago, when a political row over the expansion of quotas for jobs and university places exploded into a de facto civil war, with at least 50,000 people displaced and more than 200 killed.

It was around two months into the conflict, on 4 June, when Hangsing recalls going to the ground floor of their relief camp accommodation to get some water. “My seven-year-old son Tonsing was jumping on the first floor and calling after me,” he tells The Independent.

“‘He Pa! He Pa!’ (Papa, Papa) he was saying. After the third time, my wife called to me saying: ‘Something has happened to our son’.”

Tonsing had fallen on the floor, with his forehead bleeding profusely. “He had a bullet wound,” Hangsing says.

“We immediately took him to Assam Rifles’ MI (medical inspection) room [in the camp]. But there the doctors said it is too serious and needs to be treated in a hospital.”

The nearest hospital with the facilities to treat Tonsing was the RIMS hospital in the state capital Imphal, 42km away. With Imphal a Meitei-dominated area, it was not safe for Hangsing to go. Meena volunteered, he says. “She said it should be safe for her to travel, since she is a Meitei.”

One of Meena’s friends, another Meitei woman named Lydia Lourembam, volunteered to travel with her and the boy in the ambulance. “But on the way a mob of Meiteis burnt them alive, before they could even reach the hospital,” says Hangsing.

“My mother and her friend thought that because they are Meiteis they would be safe,” says his 14-year-old daughter, Nemvouvam. “[That] they will not attack them. But they burnt them alive.”

The family did not hear any news about what had happened to Tonsing, Meena and Lydia for the next two days, he says. “My father-in-law told us after it was published in some local newspaper. And after that all we got of my wife and son was a few burnt pieces of their bones.”

A month after the incident, his daughter says, Hangsing does not like to speak about them. “It only brings back the horror. He cries at the mention of my mother and my brother and all that we have lost in them.

“But you know they live with us forever. They will be with us forever.”

With Meiteis and Kukis now effectively segregated in Manipur and maintaining their own military-style bunkers and territorial borders, local police and authorities – bolstered by around 10,000 members of the federal armed forces – are still stretched just maintaining peace more than four months after the violence began on 3 May.

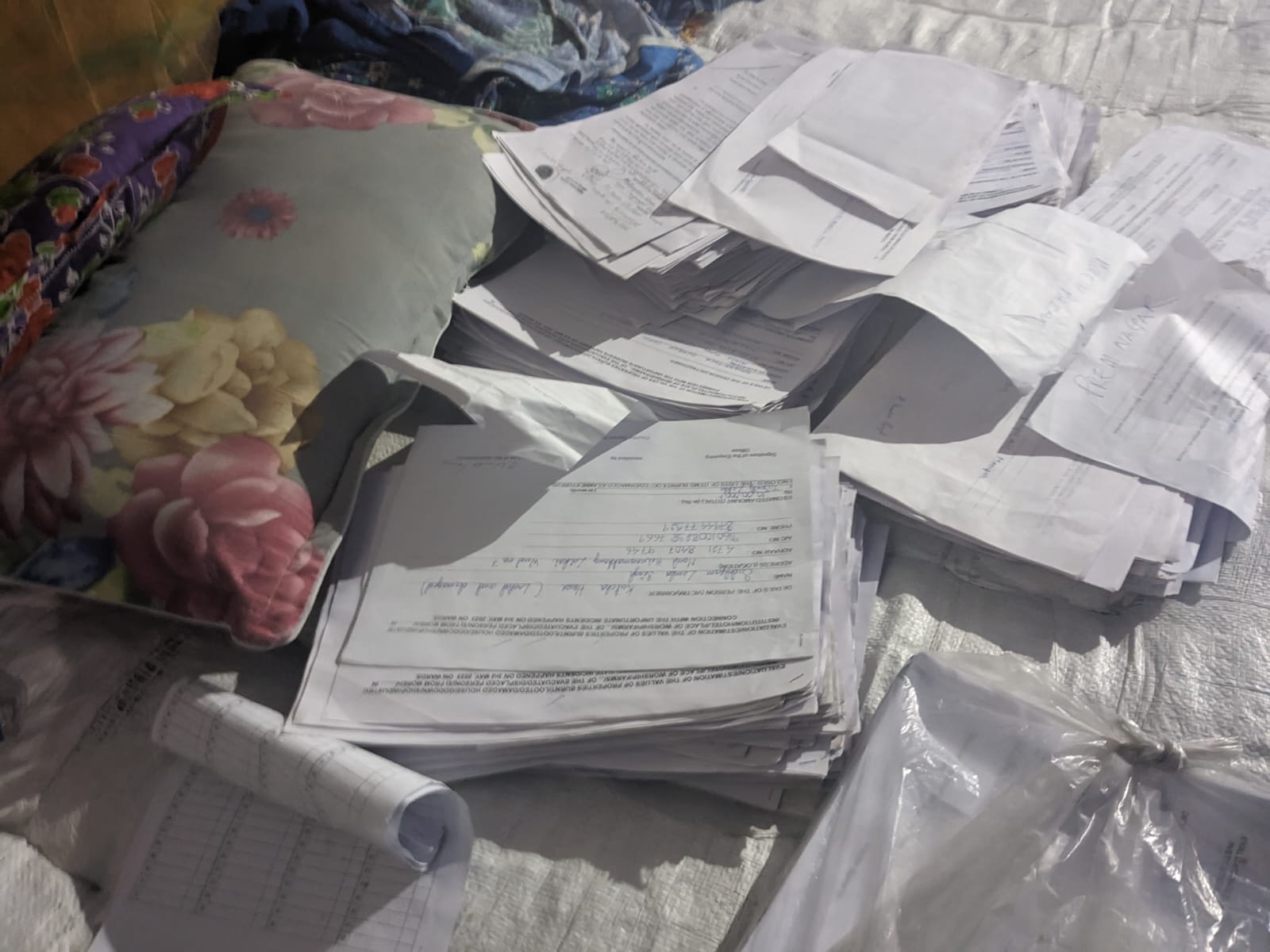

The Hangsing family have been given no information about an investigation into the deaths, or whether police have any suspects in the case. The family is calling for a federal probe to be opened by the National Investigation Agency (NIA).

“While [my father] had appealed to both the sides for peace, he also wants an NIA probe in all the crimes by both the groups,” says Nemvouvam. “We want peace and justice.”

Like the Hangsing family, 36-year-old Boisi fled her Kangkpopki home when the violence began in May. She now lives in a Kuki relief camp some 105km away in shared accommodation with 18 people.

Unlike the other 682 residents of the camp, however, Boisi is a Meitei woman. Her camp is located in the Kuki-dominated district of Churachandpur, where all the Meitei-owned houses have been burned to the ground and armed militia guard the “border” to prevent Meiteis from entering.

Boisi met her husband, a Kuki man, in a more peaceful time in Kangkpokpi. “Our villages were adjacent to each other,” she recalls. “And every year we used to have this folk dance called thabal chongba. In the dance, men and women joined hands and hopped to the rhythm of drums in a circle,” she says as she giggles, covering her face. “It was during one such dance in 2003 that my husband first saw me. And that’s how we met.”

For decades the two groups have lived peacefully in the area, she says. So, when the two decided to marry, despite her young age, it was not considered a particularly big deal.

That’s why the violence on 3 May was such a shock, she says. “We fled the village on 4 May itself. We had already heard about the violence in a neighbouring village a day earlier. About 30 or so houses were burnt down. We fled the village before Meitei miscreants reached our homes.”

Since then Boisi, her three children and her husband have been living in this makeshift camp on the site of a school. There are no actual beds, so layers of sheets cushion the floor, and benches and study desks have been arranged to divide what was a classroom up into a small area for each family.

Sheets have been hung up over the desks to give each family a semblance of privacy, and a makeshift kitchen in the corner is stocked with nothing more than a few bottles of water, an electric cooker and a handful of utensils.

It is a far cry from the life she had enjoyed with her husband for 20 years, a fragile existence that is shared by tens of thousands of others in Manipur who are waiting anxiously for peace talks between the two sides to bring some kind of resolution.

Prime minister Narendra Modi has spoken only a few times publicly about the situation in Manipur, which the opposition Congress party says represents a failure of his government to maintain law and order. The Manipur state government in also led by Modi’s BJP.

“Peace is slowly returning to Manipur,” Modi declared from the ramparts of the Red Fort in his mid-August Independence Day address, yet since then there have been several more high profile incidents of violence, with an Indian Army officer abducted and killed only last weekend.

At their camp, Boisi and her family just want to return to their former life, and in the playground outside the classroom there are glimpses of normalcy as a few children play with a ball.

But she is clearly aware of the dangers she faces. Asked if she has her own thoughts on the cause of the state’s conflict, she looks out to the field. After a long silence she politely says “no”, and asks not to be questioned further. As a Meitei woman living among Kukis, she knows that speaking her mind is a luxury she cannot afford.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments