Why the world’s most populous country is running low on bodies

Lack of systemic support for body donation, logistical hurdles, and cultural and religious sensitivities force medical students to rely on anatomical models or digital simulations for training. Namita Singh reports

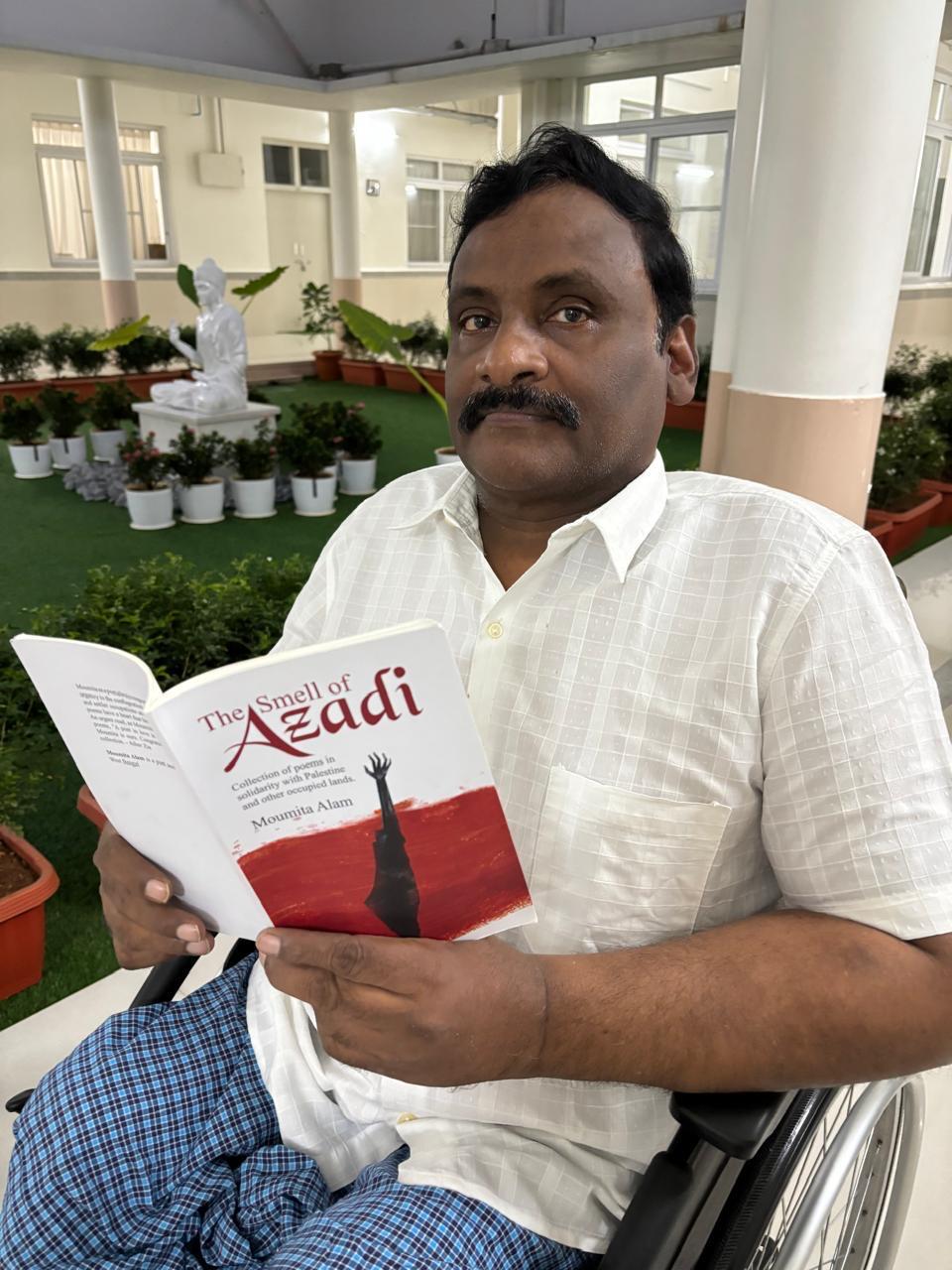

When GN Saibaba, a university professor who had spent years in prison for his impassioned activism in India, died last month, his final act of service was an unexpected one: his body became a teaching tool, donated by his family to the Gandhi Medical College in Hyderabad for academic and research purposes.

Saibaba’s wife Vasantha and their daughter Manjira had only a short window in the hours after his death to consider whether to go ahead with the donation, and decided it would be a fitting send-off, embodying the late teacher’s lifelong belief in “education as a tool for liberation”.

His was one of the most high-profile body donations in recent memory in a country where such sacrifices are rare. The previous month, the family of the veteran Communist Party leader Sitaram Yechury also made national headlines for donating his body for teaching and research purposes.

The donations, while primarily intended to honour the legacies of the two public figures, have also cast a spotlight on a wider and growing problem in the world’s most populous nation: an acute shortage of cadavers for medical education and research.

For a country with one of the largest healthcare systems and a rising number of medical students, the supply of cadavers is alarmingly low, and the situation risks harming the quality of medical training, professionals and activists tell The Independent.

The federal health ministry doesn’t keep a public database of body donations, but the seriousness of the problem can be gauged from an appeal it made to the health secretaries of states and union territories earlier this year.

The Hindu reported in July that the director general of health services, Atul Goel, had told the regional bureaucrats: “We have a shortage of human cadavers required for teaching in the country.” He urged them to encourage families to donate the bodies of their departed loved ones instead of just the organs. “This will go a long way in offsetting the shortage of human cadavers in medical institutions,” he said.

Dr Vaishaly Bharambe, anatomist and cadaver donation advocate, says that India needs people to come forward with bodies “more than ever to meet the growing demands of medical education”, but the donation system “has not kept pace”.

“The shortage means many students are forced to rely on anatomical models or digital simulations, which cannot fully replicate the experience of real dissections,” she says.

Instead of one cadaver for 10 medical students – the required rate, Bharambe says – India likely only has one for every 50 students in some colleges. This is leaving a generation of aspiring doctors without critical practical training, profoundly affecting the quality of care they can provide.

At the heart of the cadaver shortage is a lack of systemic support for body donation, compounded by cultural, religious and logistical hurdles and a lack of awareness, activists and doctors tell The Independent.

“Around 2017, we were receiving numerous calls asking how and where to donate,” says Sunayna Singh, chief executive of Organ India, an NGO supporting organ and cadaver donation, noting the absence of accessible information for potential donors and their families.

In response, her team undertook a year-long project to create an online directory. “We contacted medical colleges across India, so now, if, say, you are in Karnataka, you can visit our site, select your state and city, and see a list of colleges with their contact details. We wanted to simplify the process so people wouldn’t have to search endlessly for information.”

The NGO has a team of people to help donors and coordinate with medical colleges to ensure that the donation process goes smoothly. But sometimes, their best efforts aren’t enough.

Singh describes an incident that took place during the Hindu festival of Dussehra in October. “We got a call from Hyderabad, and they said a family member had died and they wanted to make the donation,” she recalls. “They were very specific about the college they wanted to donate to. I wanted to get it to the college, but it was the Dussehra weekend. Everyone had gone home.

“Basically, we tried – we really tried hard. We also tried to speak to other nearby colleges. But it did not happen, because it was, you know, a holiday weekend,” she adds, disappointment ringing in her voice, as she calls for better-organised support from hospitals and from state and federal governments.

“If the colleges could have somebody standing by 24/7, even during holidays, to make sure it’s coordinated and done efficiently; if the ambulance is sent to the person’s house. It is a big deal for people to donate their bodies. And death doesn’t come on weekdays and from 9 to 5,” she says.

For families like Akhil Wagh’s, body donation is a profound final act of giving. His father, Jayaprakash Wagh, wanted to donate his body when he died, and Akhil’s mother, Mamata Wagh, decided to do the same. “After all, what use is a body if it’s simply burned? This way, it lives on, helping students learn, maybe even saving lives one day,” Wagh, who lives in Chicago, recalls her saying.

The family initially registered for body donation at an ayurvedic hospital in Pune, the western Indian city where his parents lived. The hospital, however, made it the family’s responsibility to transport the bodies. So they approached a private hospital instead, which agreed to take care of transportation and documentation.

When Wagh’s father died last year, the family’s commitment was put to the test. He was expected to be discharged from a Pune hospital when he suffered a sudden heart attack. Wagh was away in the US, and it was left to his mother to ensure that her husband’s last wish was honoured.

“My mother handled it all,” Wagh says. “She had to manage the doctor’s certificate, the death certificate, and coordinate with the hospital. And she did it alone, with incredible strength.”

This is not easy for a family member to do in that moment. “We do not give credit that the moment they lose their family member, they have to make that call. Instead of grieving, they have to make that call to a medical college,” Bharambe says.

“They are looking at a six-hour window in which they have to complete all the paperwork and the body donation,” she adds. “For a country as warm as ours, one should make the donation within six hours of the person passing away. The idea is that the donor and his family should have minimum pain when the donor dies and his body begins to degenerate at the end of six hours.”

But the process is arduous.

“First, a family member needs to provide an Aadhaar card to identify the body and confirm the donor’s identity,” Bharambe says, referring to India’s national digital ID card system. “There is always a risk that someone might attempt to pass off a body as their relative’s to cover up a crime, so this verification step is crucial.”

Medical documentation is also required, including a certificate specifying the cause of death. “In some states, it’s also mandatory to register the death with the municipal corporation before moving forward with the donation,” she says.

Completing all this paperwork can take time, especially if the death occurs late at night.

“Imagine someone dies at midnight,” Bharambe says. “Finding a doctor to issue a death certificate in the next couple of hours is challenging, and that delay can make the entire process more difficult for the family.”

There are also legal restrictions that further narrow the pool of potential donors. Bodies that undergo post-mortem exams, belong to accident victims, or come from patients with diseases such as Aids or tuberculosis, cannot be used in educational dissections, says Bharambe.

She explains the procedure for handling and preserving a donated body on its arrival at a medical college. “Once the body reaches the college, it undergoes a wash and is then injected with embalming fluids. These fluids act as preservatives, preventing decomposition and allowing the body to be used for medical education. The body is placed in an embalming loop to ensure that it stays intact and suitable for use over time,” she says.

“Throughout the next year, students will dissect and study the body in stages, learning and understanding the intricacies of human anatomy. The medical student actually studies with the feel of a cadaver when it reaches the surgery department. He is much more aware of what a muscle feels like. He is not dependent on his imagination, because it comes to him naturally.”

Advances in technology mean that medical students can now use virtual human cadavers for their studies, but Bharambe says it isn’t the same.

“You wear your goggles, and what you see in front of you is a cadaver. You can remove muscles, put them back. It’s a study in three dimensions,” she says. “Will [virtual bodies] replace cadavers? It cannot ever replace the feel of a real human being.”

There is no technology, she says, “that will allow you to imagine what different organs inside a person feel like. You have to have a cadaver.”

Religious and cultural beliefs around death and the afterlife further complicate the picture. Many families like to perform religious rites soon after death, and they may hesitate to disrupt these rituals by donating the body to science, or fear being denied a moment of closure.

“People fear they won’t be able to complete these important ceremonies,” Bharambe says. “Sometimes families ask if they can receive any part of the body for closure, but the law in India strictly prohibits this,” she adds. “While there is ongoing research on ways to help families feel a sense of closure, current law provides no options for returning remains to loved ones.”

Once a donated cadaver has served its teaching purpose, government regulations require it to be incinerated. “Hospitals either have their own burial grounds or partner with biological incinerators, so religious rituals are not involved at this stage,” says Bharambe.

Saibaba’s wife is still grieving the loss of her “childhood friend, lover, and partner”, but she finds solace in the knowledge that his final act aligned with his belief system. “This is the least we could do to honour him,” she says. “He always wanted to teach, to impart knowledge.”

Reflecting on the emotional challenges of giving your loved one’s body away, Vasantha says: “The college said we could visit him any time. But he’s in my heart, in my eyes and in my thoughts. Seeing him again would change nothing. He’s already here with me. His body now serves students who can learn from it, just as he always wanted. I have given them the responsibility.”

A few weeks after his father’s death, Wagh returned to India and went to the private hospital the body had been donated to. He says he felt a sense of peace. “I didn’t need to see him one last time. I just needed to know that he was where he wanted to be, fulfilling his purpose. It’s comforting to know that his body will serve others, that his life continues in a way.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks