Cheetahs to arrive in India for historic reintroduction project – but can they survive battle of the big cats?

Close to a hundred more powerful leopards will be waiting on the other side of the fence for the eight cheetahs arriving in India on Saturday, reports Arpan Rai. And that’s not to mention the wolves, hyenas, village dogs... and tigers

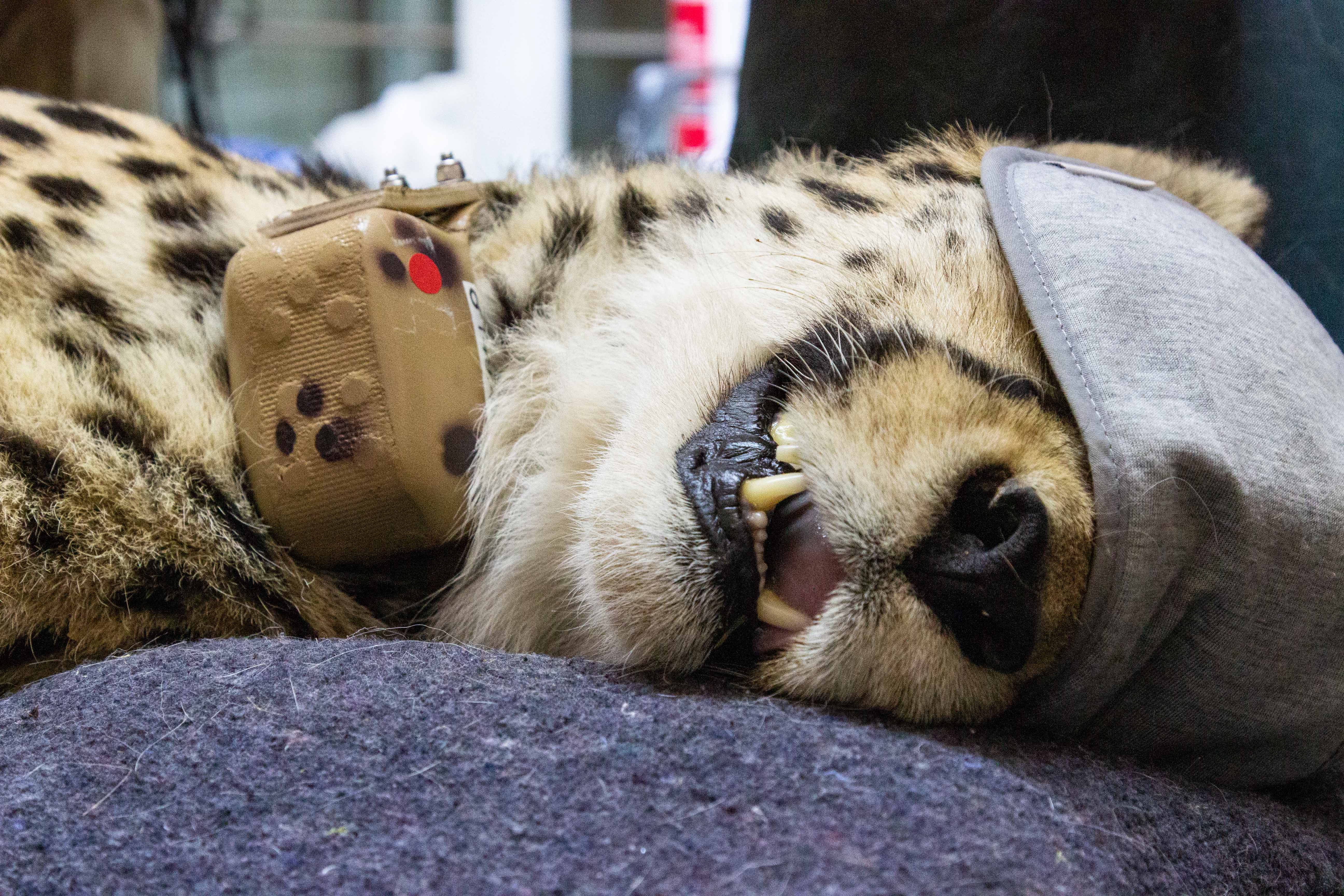

Eight Namibian cheetahs are travelling across continents in a drugged state of slumber, heading for an uncertain future as part of an historic and controversial attempt to reintroduce them to India.

When they finally wake up on Saturday after an 11-hour journey including a private jet and helicopter, they will be greeted by none other than the prime minister of India himself, Narendra Modi, whose birthday celebrations include the honour of releasing the animals into their bespoke enclosure.

Their new home is in India’s Kuno National Park, a protected area spanning around 750 sq kms (289 sq miles) in Madhya Pradesh, although they will not have access to the whole park just yet. First, the chosen cheetahs – five females and three males – will step out into a restricted paddock 5 sq kilometres (1.3 sq miles) in size where they will begin adapting to the water and air, flora and fauna of India.

The authorities managing the project in India and Namibia are giving the spotted big cats around a month to acclimatise in the smaller enclosure, after which they will be set free to explore their new home and hunt for their most likely prey of spotted deer.

But in that moment a new and very real threat will emerge, and one which will most likely dictate the success or failure of this project to reintroduce cheetahs to India for the first time since they went extinct in the late 1940s.

Close to 100 leopards – a much larger and more muscular species – will be waiting on the other side of the cage, setting the stage for an almost inevitable territorial battle of the big cats.

In any head to head in Kuno, the leopards would tear the cheetahs apart, one of India’s top wildlife conservationists Valmik Thapar tells The Independent.

The cheetah, he explains, is a delicate predator unlike any other member of the big cat family, using its unrivalled speed and stealth to catch its prey. Never mind leopards – hyenas, wolves and even village dogs all pose a potentially lethal threat.

Indian officials have installed electrical fencing 3.2 metres high around the whole of the cheetah enclosure, hoping this is enough to deter other wild animals from getting inside. Already this is raising alarm bells among independent experts, who argue a minimum fence height of 4.5 metres is required.

“Hyenas, which are found in Kuno by the dozens, will eat the cheetahs alive. Hyenas, leopards and lions are the enemies of the cheetahs in Africa. In India, it will be tigers, leopards and hyenas. There is a constant risk to cheetahs from village dogs who roam wild on the edge of these areas,” says Thapar, adding that the park has more than one hundred villages on its periphery and at least 2,000 village dogs roam these areas.

It is likely that cheetahs will also eventually encounter tigers in India, warns Thapar, saying the latter utilise a corridor stretching from Rajasthan to Madhya Pradesh.

“Tigers from Ranthambore (one of India’s most famous national parks in Rajasthan) move in the corridor to Kuno. In the last six months, one of our tigers from Ranthambore returned to the national park from Kuno,” he adds.

Even the Namibia-based Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), which has been heavily involved in the relocation project, is cautiously optimistic but has said there will a host of challenges.

Leopards are “sneaky” creatures, says Dr Laurie Marker, CCF’s founder and executive director, acknowledging that these tree-climbing ambush pretadors are likely the biggest challenge the eight cheetahs will be up against.

Despite the fact that the species is rated vulnerable with fewer than 7,500 remaining on the planet, the authorities in India are prepared to lose a cheetah or two if it comes down to a fight.

“We are prepared to take the losses of cheetahs. Even though we don’t want to lose a single cheetah, and the authorities in this project will go out of their way to save the cheetahs, they must be prepared for certain casualties,” says Dr MK Ranjitsihn, India’s veteran conservationist and wildlife expert and the original architect of the cheetahs’ introduction in India.

Cheetahs, Dr Ranjitsihn insists, can look after and defend themselves. And ultimately, park rangers will not seek to intervene too much.

“If a tiger walks in [to Kuno], we won’t drive him away. We are not going to throw them out,” the conservationist says.

Experts working on boosting cheetah populations in Namibia are concerned about the idea of turning the Indian national park into a wrestling ring for clashes between the two cats.

“In Namibia, among all the large carnivores like lions, spotted hyenas, leopards, wild dogs and cheetahs – cheetahs are always the weakest one,” Dr Bettina Wachter, head of the Cheetah Research Project, tells The Independent from Namibia.

Visibly concerned as she expresses her scepticism about the project as a whole, the researcher says it is not fair on the cheetahs to treat their reintroduction as a case of trial and error.

“As conservationists, we have a responsibility towards vulnerable, threatened and endangered species,” the scientist says.

Thapar resonates this concern in Delhi, saying that “any cheetah lost in this process will be a disaster, because it is one of the most beautiful endangered animals on our planet”.

“You’re going to bring an exotic species here which is going to face a tremendous threat in any case,” he says. In his view, it is unrealistic to hope – as the Indian government does – for African cheetahs never before seen on this continent to simply slot into the ecological balance of the Asian landscape.

He says that in the last 300 years, since the British started keeping written records of their hunting and wildlife-spotting exploits in India, there is not a single record of any natural, healthy population of cheetahs in the wild in the country. “Nobody can claim that record – there are only instances of cheetahs being killed over the last 300 years in India.”

Contrast this with the cheetah kingdom in east Africa’s Tanzania, he says.

“If today you go to Serengeti, you’ll run into a cheetah mother with her cubs, another set of three mother cheetahs, you run into male cubs and their coalitions. There is no such record of cheetahs thriving in India,” the Indian naturalist says.

Some critics have also argued that this project does not truly represent reintroduction, as the cheetahs found today in Namibia are a distinct subspecies to those that once roamed India. There are in fact five subspecies of cheetahs in total, with two – the Asiatic cheetah that is now only found in Iran, and the northwest African cheetah – listed as critically endangered. The cheetahs involved in the project are of the Southern African subspecies [Acinonyx jubatus jubatus], listed as vulnerable.

But for the CCF chief, the distinction evaporates in the face of the animal’s adaptability. “They’re all the same. Cheetahs are cheetahs, very adaptable. And I’ve seen them in every area they live in and they’re all pretty much the same,” Dr Marker tells The Independent, the day before the cheetahs’ take-off from Namibia.

To bring a wild animal to another landscape is always an uphill task, and the officials bringing the cheetahs from Namibia are aware of this.

Dr Ranjitsihn argues that the possibility of conflict should not preclude such projects from being attempted. “Look in the wild, there will [always] be conflict. There are a number of options – shy away and say we are scared of losing a single cheetah, and we will not do it.

“The second option is to expel leopards from the region... and the third option is to take the chance,” he says.

Dr Marker, who has been canvassing Kuno for a decade for this project, says that the potential upsides far outweigh the risks: “When you talk about getting an animal back from the point of extinction, you pretty much have to give it everything you’ve got.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks