Amnesty’s India chief on Modi’s shrinking of space for activism and why he won’t abandon his post

Amnesty’s India operations have sparked a head-on clash with Narendra Modi’s administration, but Aakar Patel, the man at the helm, tells Arpan Rai he is not going down without a fight

For a man going toe-to-toe with the state in the shrinking battleground of human rights activism in India, Aakar Patel is surprisingly upbeat about dealing with the government agents who raid his office from time to time.

“Maybe I should make some money by starting a class teaching people how to handle investigative agencies and their officers,” jokes the chair of the board at Amnesty International India.

Plans for an interview with The Independent at Amnesty’s India office had to be hastily rearranged because “there’s not much space to sit amid [case] files”. Patel, a former journalist turned author and activist who operates out of the southern city of Bengaluru, isn’t exaggerating.

He and Amnesty are currently dealing with at least 11 separate defamation and criminal cases, translating into the mountains of paperwork that now dominate any functional space within the organisation’s premises that might have been used for day-to-day operations.

Amnesty’s persistent criticism of the government’s rights record since Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 has come at a high cost for the NGO – one of many in India to have had its operations curtailed by the authorities. In August 2020, its work came to a grinding halt when the government froze its bank accounts and raided this office in Bengaluru.

That was only one of a flurry of raids carried out by various authorities, with the government’s financial crimes agency eventually bringing charges of money laundering against the organisation. They accused Amnesty of restructuring its India operations in order to continue receiving foreign funding, after its permission to do so was revoked by the government.

In April 2022, when Patel was heading to the airport to deliver a series of guest lectures at American universities, the authorities stopped him at immigration and told him he would not be permitted to board his flight. That’s when he learnt that his passport had been impounded and he was on an “exit control list”.

No longer able to travel abroad, Patel now keeps a go-bag, containing a few changes of clothes and a toothbrush, at hand for a very different reason – the worst-case scenario of facing jail time. He divides his time between home, office, court hearings, and working on his book projects.

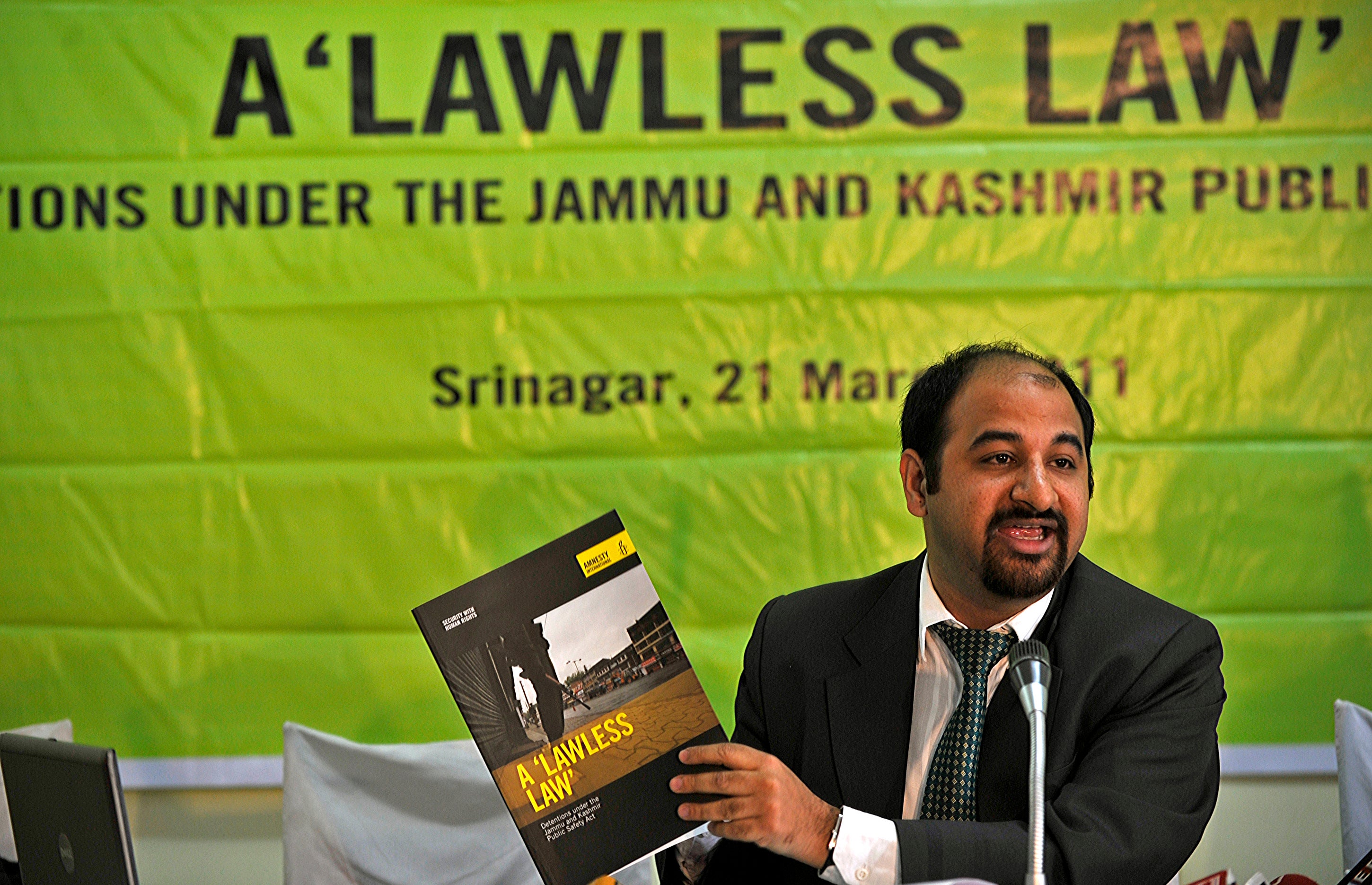

The 53-year-old was born and raised, like the prime minister himself, in the western state of Gujarat. He worked as a legal reporter in the 1990s before rising through the ranks to lead the newsroom a decade ago. He made the switch to full-time human rights activism not long after Modi came to power, heading Amnesty’s India operations from 2015 to 2019, at a time when the organisation was among a number of groups highlighting the government’s crackdown on political leaders, its jailing of activists, its attempts to constrain the media, and its human rights violations in sensitive areas, including in the highly militarised federal territory of Kashmir.

“These authorities were unnecessarily agitated about the work we did. They kept asking, ‘Why are we working on Kashmir’s human rights situation?’ I was like, ‘Why should we not work on this?’,” he says.

He laughs as he recalls the exchange. “They are not used to people who are not begging for mercy,” he adds.

“All the complaints, FIRs, and charge sheets Kashmir police filed against India’s armed forces for committing rapes and murders – not a single one has been responded to by Delhi’s Ministry of Home Affairs. Not even the Kashmir government has gotten a reply from New Delhi,” says Patel.

During a raid at the Amnesty office, Patel asked one of the officers whether the organisation’s Indian bank accounts had been frozen or would be frozen imminently. “He said in a somewhat aggressive response: ‘Sacrificial lambs are never told their throats will be slit the next morning.’

“There was absolutely no reason for him to show he was so tough,” says Patel.

The licences of more than 20,600 NGOs in India have been revoked in the past decade, with nearly 6,000 of these cancellations taking place since the beginning of 2022, according to data from Amnesty International. Most of the NGOs in India have reduced their staff by 50 to 80 per cent.

Indian officials have brought “terrorism-related charges, amongst other things, to prevent organisations and activists from accessing essential funds”, Amnesty says.

Patel says he has had to pay the salaries of staff out of his own pocket after their bank accounts were frozen in August 2020.

“I don’t find it depressing. One of the cruel things about writers is that you can detach from current affairs and look at it through a microscopic lens, which is something someone living it will not be able to,” he says.

“What that means is that, as an upper-caste or upper-class male, I can read or say whatever I want to do but I am not rotting in jail. Umar Khalid, had he been in my place, wouldn’t have been in jail,” says Patel, referring to an activist who was imprisoned after being charged under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act and has had several bail hearings postponed.

Indian police arrested Khalid, 36, a former student leader who had frequently criticised the Indian government, in 2020 and accused him of being a “conspirator” in religious riots in Delhi that left more than 50 people dead and thousands displaced.

“What is depressing is that we have a corrective in our hands to change the focus of discussions in India’s domestic affairs – and I am not talking about power. The BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] can be in power. We can shift the focus from a nation going after itself and after its own, and look to something more positive,” says the 52-year-old activist.

“I don’t disagree with someone who wants to see a strong India. That’s fine. You don’t want a large army, fine. You want to thumb your nose to China, fine. I don’t have a problem with any of that. I have a problem that India’s nationalism is inward-looking,” Patel tells The Independent.

Tensions between India’s majority Hindus and minority Muslims have risen since Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP government took power in 2014. The rate of hate crimes against Muslims has increased, and monitoring groups have documented hundreds of incidents of political hate speech, including by senior figures in the BJP.

“The attention and energy is focused on ‘what new mischief we can do to go after Muslims’. Beyond a point, it’s not only boring – which it is – but also destructive. No nation can succeed if it goes after a sixth of its population,” Patel says.

Hindu leaders, ministers and fringe groups can’t expend all of the national energy on going after minorities, he says. “It’s disgusting.”

Given the diminishing space for NGOs in India and the sustained pressure on Amnesty from the authorities, Patel might be forgiven for considering alternative employment. But he insists that is no longer an option.

“It would be dishonest of me if I were to look away from what is happening in the country and write about something else. As somebody who is in the human rights space, and I am observing current affairs – the logical thing for me will be to write on the subjects I know,” Patel says.

“This is what I really do: I think I identify with human rights globally, and what it stands for. I think, on the contrary, that is the only way we can engage with the country’s current climate in a meaningful way.

“I can’t be a politician, that’s a lot of hard work,” he jokes.

Amnesty’s India arm is one of just a handful of major human rights organisations still operating in India with some liberty, although legal proceedings and court hearings continue to be a significant distraction.

The challenge for Amnesty is not just to shine a spotlight on human rights issues in the country, but to persuade ordinary Indians to stand up and take notice. Modi remains hugely popular across the country, especially among his Hindu base, and is widely expected to win a rare third term in a general election beginning on 19 April.

“What the BJP has done, and I think successfully, is it has injected polarisation and hate into the society. You can have the most educated person be a bigot in society,” says Patel. Even if the BJP’s dominance of elections eventually fades, he says, “their polarising effect will take longer to wean off”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks