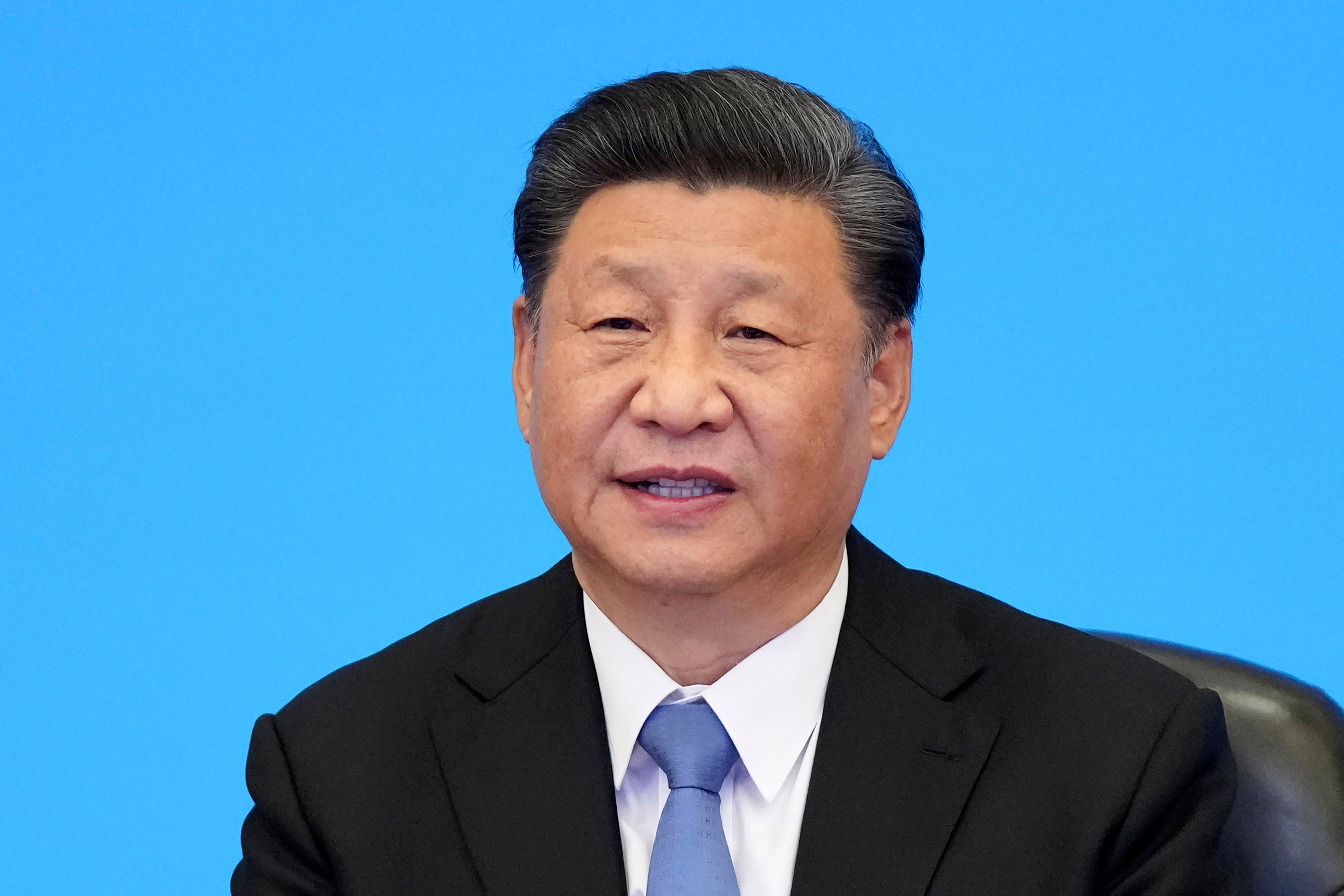

Xi takes aim at China’s wealthiest to address income inequality, but the answer may lie with local government

President Xi has focused on halting the wealth expansion of Chinese tech giants, but some analysts say local government retain too large a share of national income, writes William Yang

Xi has made poverty alleviation one of the central missions of his regime since he came to power in 2012 and China does have a serious problem with income inequality. According to Bloomberg, the richest 20 percent in China earn 10 times more than the poorest 20 percent.

Over recent days, President Xi has called for high salaries to be regulated at an economic meeting.

Speaking at the Chinese Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, Mr Xi reportedly called on ministers to “regulate excessively high incomes and encourage high-income groups and enterprises to return more to society”.

Xi’s government has tried different ways of bridging the income gap by focusing on poverty reduction in rural areas while halting the wealth expansion of Chinese tech giants as well as criticizing celebrity culture.

China’s richest entrepreneurs have come under increasing pressure, such as the cancellation of internet tycoon Jack Ma’s initial public offering (IPO) of his Ant group, which was set to be the biggest ever, after he criticised financial regulators, and new regulations targeting China’s booming tutor industry.

Mr Xi has also recently highlighted efforts to forestall major financial risks as a flurry of regulatory crackdowns roil China’s equity markets.

One of the area that has been identified as the pilot zone for the new initiative of wealth redistribution is Zhejiang Province, as it boasts a vibrant private sector and is home to Chinese tech giant Alibaba’s headquarter.

Some economists point out that China’s wealth inequality has reached a serious level that forces policymakers to give it all the attention it deserves. Larry Hu, the head of Greater China economics at Macquarie Group in Hong Kong, told Bloomberg that Xi’s meeting brought the issue of wealth inequality to the highest level and his comments will be the important factors that guide the direction of policymaking in the future.

Other possible measures mentioned by Pimco Asia’s China economist Carol Liao in her interview with Bloomberg include applying capital gains taxes, enhancing social security initiatives, providing incentives for charity or facilitating more government transfers to less developed regions.

Yuen Yuen Ang, author of the award-winning book China’s political economy and the global implication of its rise, wrote on Twitter that after recognizing the danger of capitalism, Xi Jinping is trying to “summon China’s own progressive era,” which she describes as “an age of less corruption and more equality,” through brute force.

Other experts point out that China’s stagnation in consumption shows that it urgently needs to increase people’s income and focus on fairer distribution. However, the move to redistribute income from rich households to ordinary households only solve one of the smaller problems with income redistribution.

Michael Pettis, a finance professor at China’s Peking University, wrote in a Twitter thread that China’s real problem with income imbalance isn’t caused by the phenomenon of the rich retaining too large a share of household income. Rather, it’s caused by the fact that local governments retain too large a share of national income, which makes households have too small a share of national income.

“For China to have a more balanced distribution of income that will allow it to rely less on trade surpluses and public-sector investment to maintain growth, Beijing must engineer a transfer from local governments to households of at least 10-15 percentage points of GDP,” he wrote.

However, Pettis also points out that some may view the suggestion as potentially destabilizing as it might require big transformation of domestic political institutions and their relationships with households.

If China hopes to maintain high growth rates over the next decade while reducing its reliance on non-productive investment, he said there are only three ways to do it: grow the trade surplus by 10-15 percentage points of GDP; discover huge new areas of productive investment equal to roughly 15-20 percentage points of GDP into which they can transfer current non-productive investment; or raise the consumption share of GDP by at least 10-15 percentage points.

“If they cannot achieve one of these three, either they should hope that there is no limit to a country’s ability to borrow and malinvest, or they should expect GDP growth to slow sharply once they decide – or are forced – to rein in debt,” he predicts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments