Jiang Zemin: China’s former president dies, aged 96

Jiang led his country after pro-democracy protests were brutally crushed in Tiananmen Square in 1989

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The former Chinese president Jiang Zemin, who led the country through a decade of rapid economic growth after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, has died aged 96.

He died of leukaemia, Xinhua news agency said, publishing a letter to the Chinese people by the ruling Communist Party.

"Comrade Jiang Zemin's death is an incalculable loss to our party and our military and our people of all ethnic groups," the letter read.

His death comes at a tumultuous time in China, where authorities are trying to suppress widespread protests against heavy-handed Covid laws and other restrictions to social freedom, while the economy is in the midst of a sharp slowdown.

Even though Jiang put down the pro-democracy demonstrations that culminated in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, some in China yesterday expressed nostalgia for Jiang's era as a time of optimism as well as hope for economic liberalisation and political freedom.

Jiang, though he could have a fierce temper, also had an informal and even quirky side, sometimes bursting into song, reciting poems or playing musical instruments – in contrast to his buttoned-up successor Hu, as well as to Xi.

Jiang had faded from public sight and last appeared publicly alongside current and former leaders atop Beijing’s Tiananmen Gate at a 2019 military parade celebrating the party’s 70th anniversary in power.

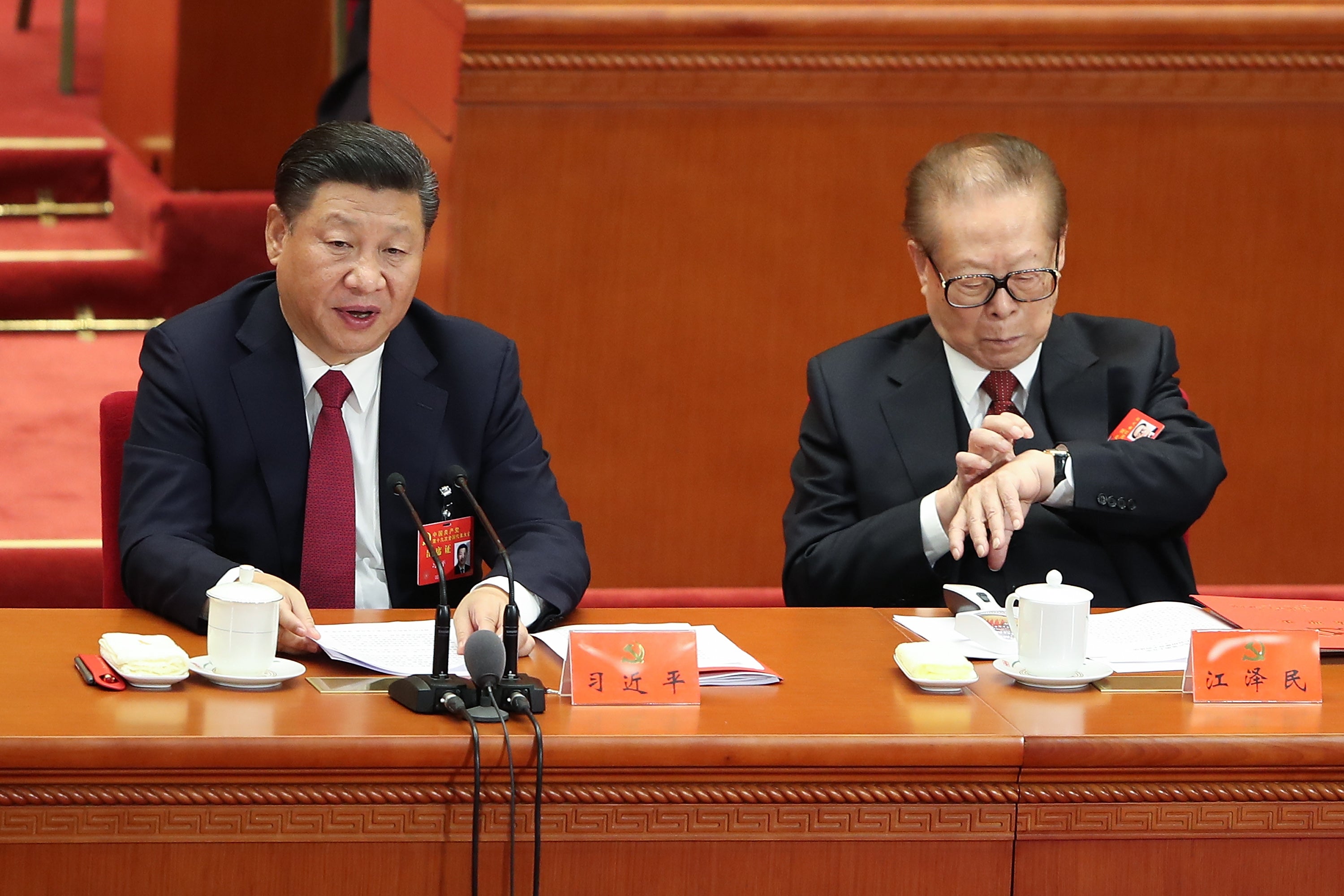

Rumors that Jiang might be in declining health spread after he missed a ruling party congress in October at which Xi Jinping, China‘s most powerful figure since at least the 1980s, broke with tradition and awarded himself a third five-year term as leader.

Jiang was born on 17 August 1926, in the affluent eastern city of Yangzhou. Official biographies downplay his family’s middle-class background, emphasising instead his uncle and adoptive father, Jiang Shangqing, an early revolutionary who was killed in battle in 1939.

After graduating from the electrical machinery department of Jiaotong University in Shanghai in 1947, Jiang advanced through the ranks of state-controlled industries, working in a food factory, then soap-making and China’s biggest automobile plant.

Like many technocratic officials, Jiang spent part of the ultra-radical 1966-76 cultural revolution as a farm labourer. His career rise resumed, and in 1983 he was named minister of the electronics industry, then a key but backward sector the government hoped to revive by inviting foreign investment.

Initially seen as a transitional leader, Jiang was drafted on the verge of retirement with a mandate from then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping to pull together the party and nation.

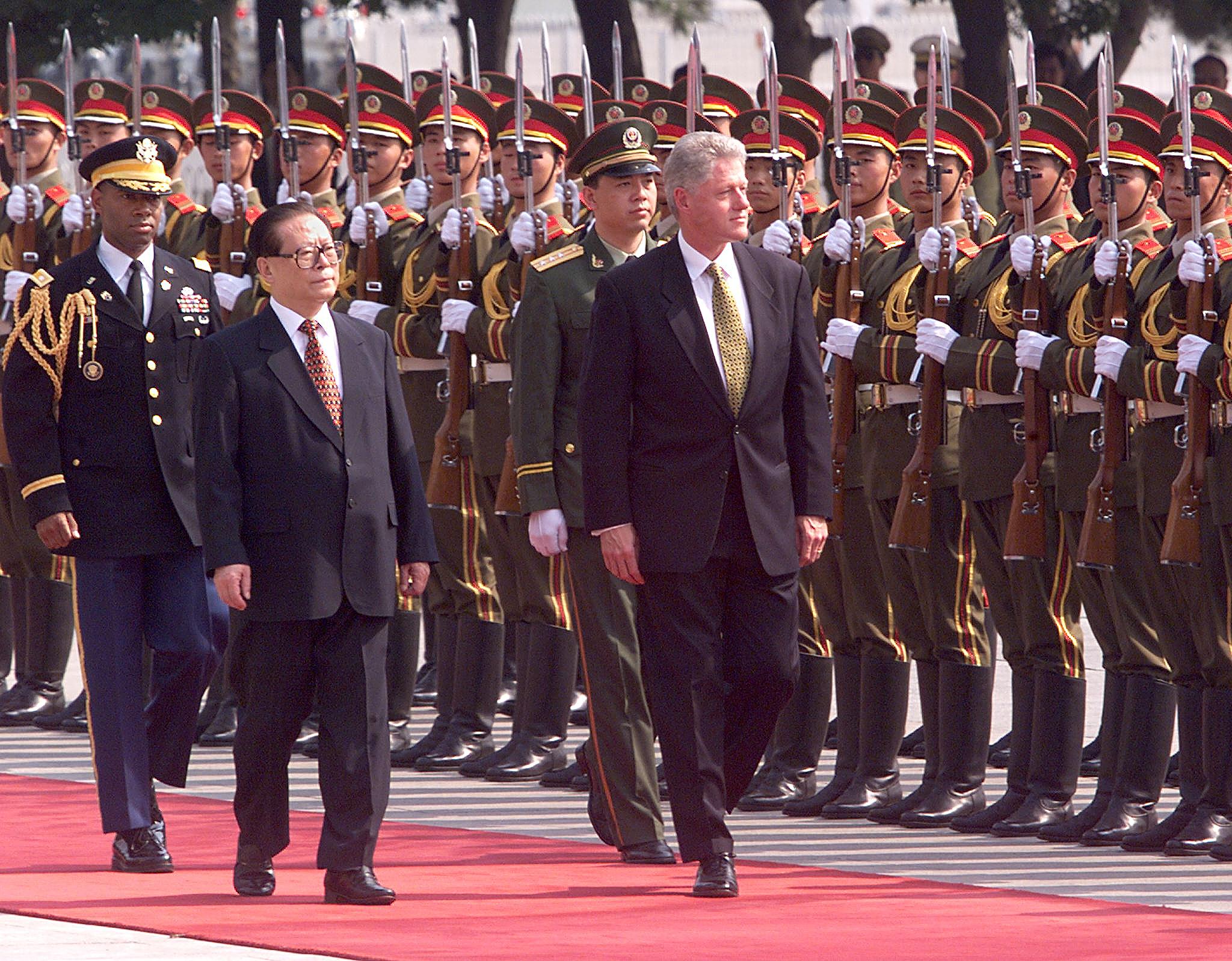

But instead he proved transformative. In 13 years as Communist Party general secretary, the top position in China, he guided China‘s rise to global economic power by welcoming capitalists into the party and pulling in foreign investment after Beijing’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001.

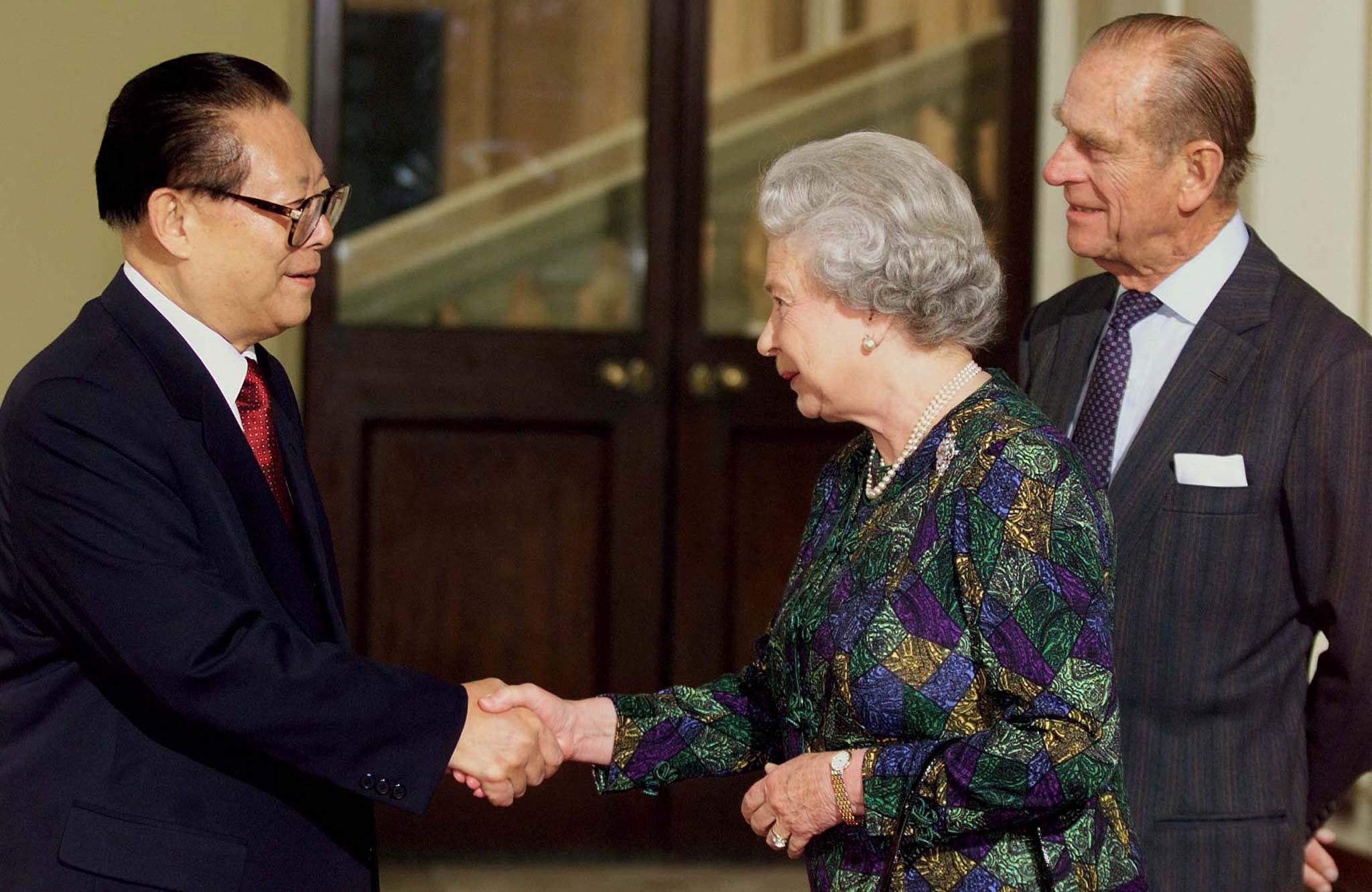

He saw China through a number of history-making changes including a revival of market-oriented reforms and the return of Hong Kong from British rule in 1997.

Yet even as the country opened up to the world, his government continued to stamp out dissent at home.

It jailed human rights, labour and pro-democracy activists and banned the Falun Gong spiritual movement, which it viewed as a threat to the Communist Party’s monopoly on power.

Jiang gave up his last official title in 2004 but remained a force behind the scenes in the wrangling that led to the rise of current president Xi Jinping, who took power in 2012. Mr Xi has stuck to Mr Jiang’s mix of economic liberalisation and strict political controls.

Jiang presided over the nation’s rise as a global manufacturer, the return of Hong Kong and Macao from Britain and Portugal and the achievement of a long-cherished dream: winning the competition to host the Olympic Games after an earlier rejection.

Jiang capped his career with the communist era’s first orderly succession, handing over his post as party leader in 2002 to Hu Jintao, who assumed the presidency in 2003.

He was an ebullient figure who played the piano and enjoyed singing, in contrast to his more reserved successors. He attempted English and would recite the Gettysburg Address for foreign visitors. On a visit to Britain, he tried to coax Queen Elizabeth II into singing karaoke.

Additional reporting from the wires

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments