A late learner’s insights into splendours of China

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

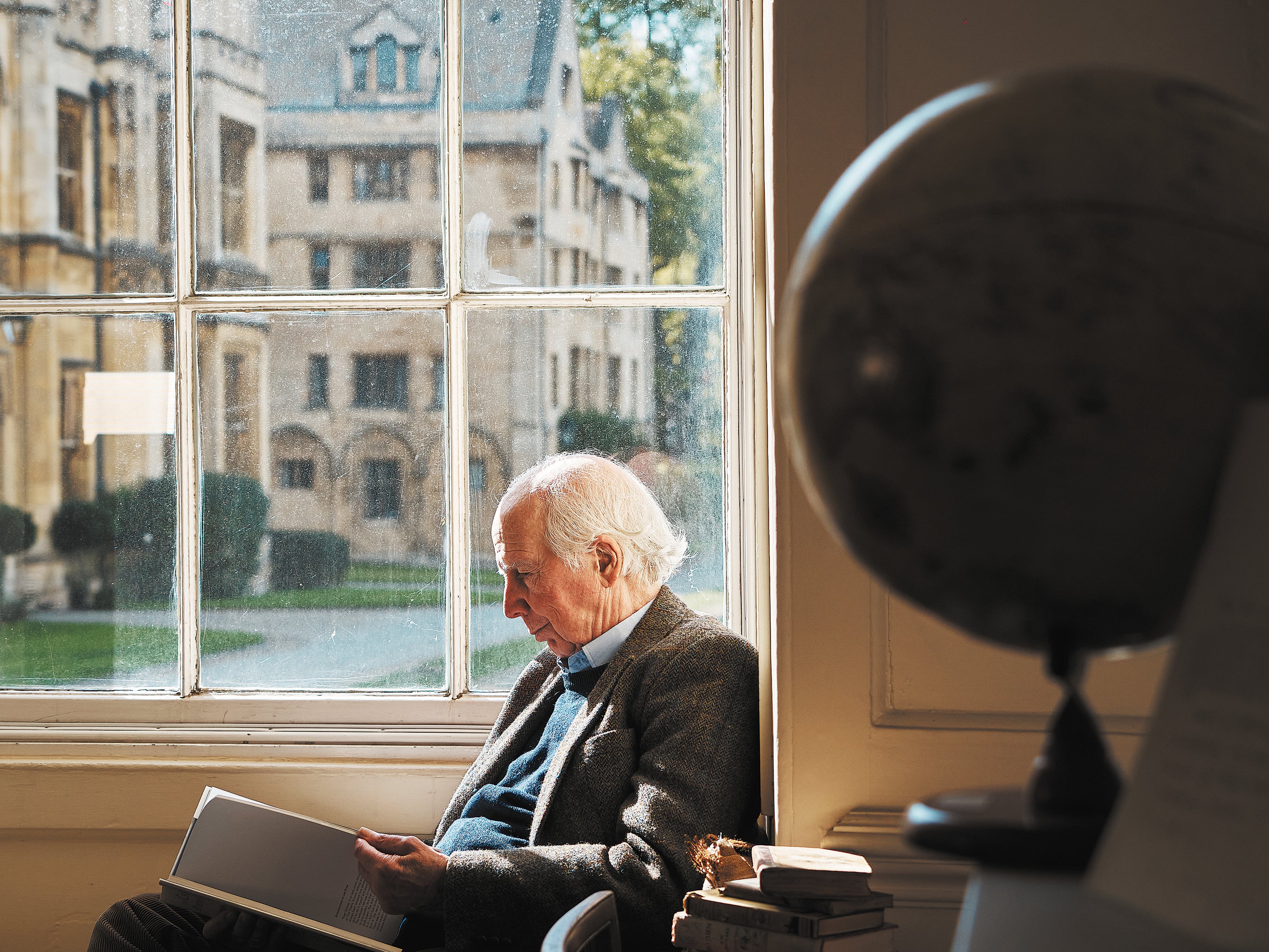

“I’d been totally ignorant of China, more or less, through my education,” Alan Macfarlane says.

Yet the 83-year-old anthropologist is now committed to building a cultural bridge between China and the West, through the exchange of shared enjoyment of culture.

An example of his commitment is the fact that, in addition to his titles of emeritus professor of anthropological science at the University of Cambridge and life fellow of King’s College, he is guardian of a granite stone standing on the bank of the River Cam that commemorates the Chinese poet Xu Zhimo.

Xu, who lived from 1897 to 1931, was an associate member of King’s College for 18 months in the early 1920s. In 1928, he wrote his most famous poem, Saying Goodbye to Cambridge Again, which has been learned by millions of schoolchildren in China.

It was Macfarlane who set the stage for the installation of the stone, and who founded a poetry and art festival in the name of Xu that has brought together poets, literati, artists and scholars from around the world each year for the past 10 years, with the aim of promoting exchanges between East and West.

The festival is by no means Macfarlane’s only project aimed at increasing understanding.

Cam Rivers Publishing, a company in Cambridge that Macfarlane co-founded with one of his Chinese students nine years ago, has been translating and publishing books by Chinese scholars in the United Kingdom and organising exhibitions that feature influential local figures who have been deeply engaged with Chinese art, as well as hosting tea-tasting ceremonies that feature selections of fine Chinese teas.

Contemplating his journey, Macfarlane now realises that one-third of his life has centred on China, and he says he knew little about the country before he turned 50.

His first visit to the country in 1996 was essentially as a tourist, but as an anthropologist who had been preoccupied with England, Nepal and Japan, his curiosity was aroused by wanting to compare the models of different civilisations and observe the contrast between East and West, as well as similarities caused largely by China’s heavy historical influence in eastern and southern Asia and the commonalities of mankind.

“I suddenly realised that the later part of my life would perhaps be devoted to understanding China,” Macfarlane says.

When he returned in 2002 the country’s transformation amazed him.

The reform and opening-up, which jump-started China becoming an economic powerhouse, had entered its 25th year of implementation. And in 2001 the country being granted admission to the World Trade Organisation and Beijing being granted the right to host the 2008 Olympic Summer Games had brought the country forward, into the limelight.

“From then on our love of China and interest in it… blossomed.”

The great changes were appealing to Macfarlane, drawing him back to further explore the land, and the following 17 years gave him and his wife, Sarah Harrison, opportunities to visit China nearly every year until COVID-19 interrupted things.

To make sense of China based on his extensive tours, Macfarlane wrote the book Understanding the Chinese: A personal A-Z, which provides vignettes that explain more than 120 concepts of Chinese characteristics, including ancestors, Confucius, eating, education, law and justice, love and marriage, and more, including how people are presented in Chinese societies, how Chinese look at certain ideas, and how those perceptions have formed.

The task that Macfarlane sets for himself is to lessen fear or discrimination by explaining a little of how China works, so that the invisible barriers, which are built from taken-for-granted assumptions, can be visible.

“It’s really about knowledge and communication. Once you get to know the other, you know why they’re doing things, why things are different, and you begin to lose that fear. And the more communication, the more people visit China, the more the West appreciates its greatness, and the Chinese already, obviously, appreciate and have imported much from the West.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks