Ancient grottoes show influences from far afield

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

Datong, in Shanxi province, North China, offers visitors a magnificent treat with special dances and music, both of which have been performed for more than 1,500 years and use some of the oldest musical instruments from East and West.

And yet the show is at times mute and still. To truly enjoy it, visitors need to make full use of their imaginations.

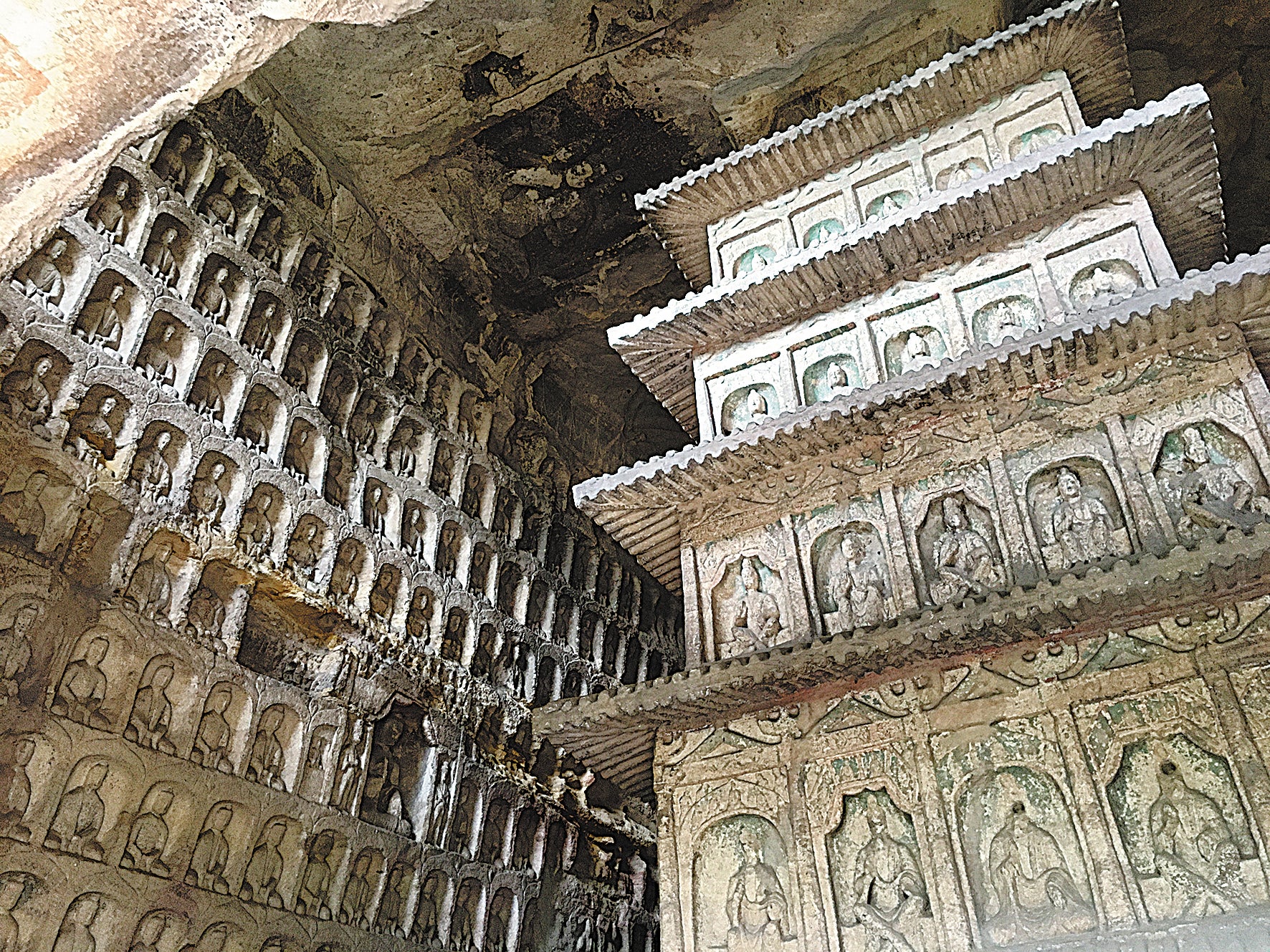

This show to celebrate artistic diversity is staged inside the renowned Cave 12 of the Yungang Grottoes, one of the most enthralling examples of Buddhist art in China.

With creativity and originality, artisans as far back as the late 5th century sculpted richly coloured, highly decorative motifs in Yungang’s dozens of grotto temples, hailing cultural exchanges in Datong, then called Pingcheng, a thriving city along the ancient Silk Road.

This vibrant musical scene is described as “the fine voices of China” by Hang Kan, dean of the Yungang Research Institute in Datong and an archaeology professor at Peking University. He says it brings together the majority of instruments that were in use in countries along the Silk Road at the time.

Yungang, stretching along a south-facing cliff, is among the country’s best-preserved Buddhist grotto temple complexes and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Between the mid-5th and early 6th centuries workers and artisans constructed dozens of cliffside caves and several hundred smaller niches. They then decorated those spaces with multi-coloured sculptures, patterns and architectural structures. Consequently, Yungang became an enduring legacy of history, art and culture.

Behind the construction of the Yungang Grottoes was the patronage of the ruling family of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534). It hoped to showcase imperial superiority and to unite different ethnic clans living in its territory in northern China.

“What makes Yungang a unique case is that, you can see it as a state project, backed by Northern Wei’s rulers and court elites,” Hang says.

Each of the first five grotto temples houses a colossal Buddha statue, at least 43 feet high, as the central icon for worship. They were built on the suggestion and under the supervision of Tanyao, a high-ranking monk cleric, and to commemorate Northern Wei’s first five emperors.

“Thereafter this massive project utilised as many resources of the dynasty as possible, in a way to produce a state prototype, or the Yungang format,” Hang says. “And it trained groups of skilful artisans who took with them the style of Yungang when moving to other parts of the country.”

The influence of Yungang is evident in the representations of Buddhist art across China, he says, including the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, Henan province, built after the Northern Wei court relocated its capital city there from Pingcheng. The model also shaped the styles of caves, statues and decorative motifs of grottoes created during the same period in Dunhuang, Gansu province, he says.

Each of the caves in Yungang sparkles with creativity as a result of encounters, exchanges and infusions of artistic styles from East and West. The introduction of Buddhist art from Central and South Asia, which also presented a strong ancient Greek and Roman influence, was merged with Chinese cultural traditions that were already well-established before Buddhism arrived, and during the process artisans developed new styles and artistic traits to express people’s outlook on life and death at the time.

The variety of sculptures also increased to include Buddha in meditation or teaching doctrines. There are also feitian (flying deities), jiyue (musicians and dancers), masculine warriors, monastics and Buddhist patrons.

More recent caves exhibit lavish patterns taken from the arts of different cultures, such as the dougong element of the interlocking wooden brackets in traditional Chinese architecture; the Pompey’s Pillar of ancient Rome; the mountain-shaped incense burners invented in China during the third century BC, and the celestial chintamani praying stones for well-wishers from ancient India.

Previously published on Chinadaily.com.cn