Artful dodger: the man who stole The Scream

A professional footballer playing at the top club in his country had everything money could buy... but it’s what he couldn’t own – a priceless work of art – that made him attempt the heist of the century, writes James Rampton

Pal Enger enjoyed a double life of which Superman would be proud. As he explains, “By day, I was a professional footballer at the best club in Norway. By night, I was the best criminal in Norway.”

Enger underscored his credentials as an underworld genius by pulling off the crime of the century. The equivalent in this country would be David Beckham stealing the crown jewels.

On 12 February 1994, as the entire police force was preoccupied with the opening of the Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Enger masterminded the most outrageous robbery in Norwegian history.

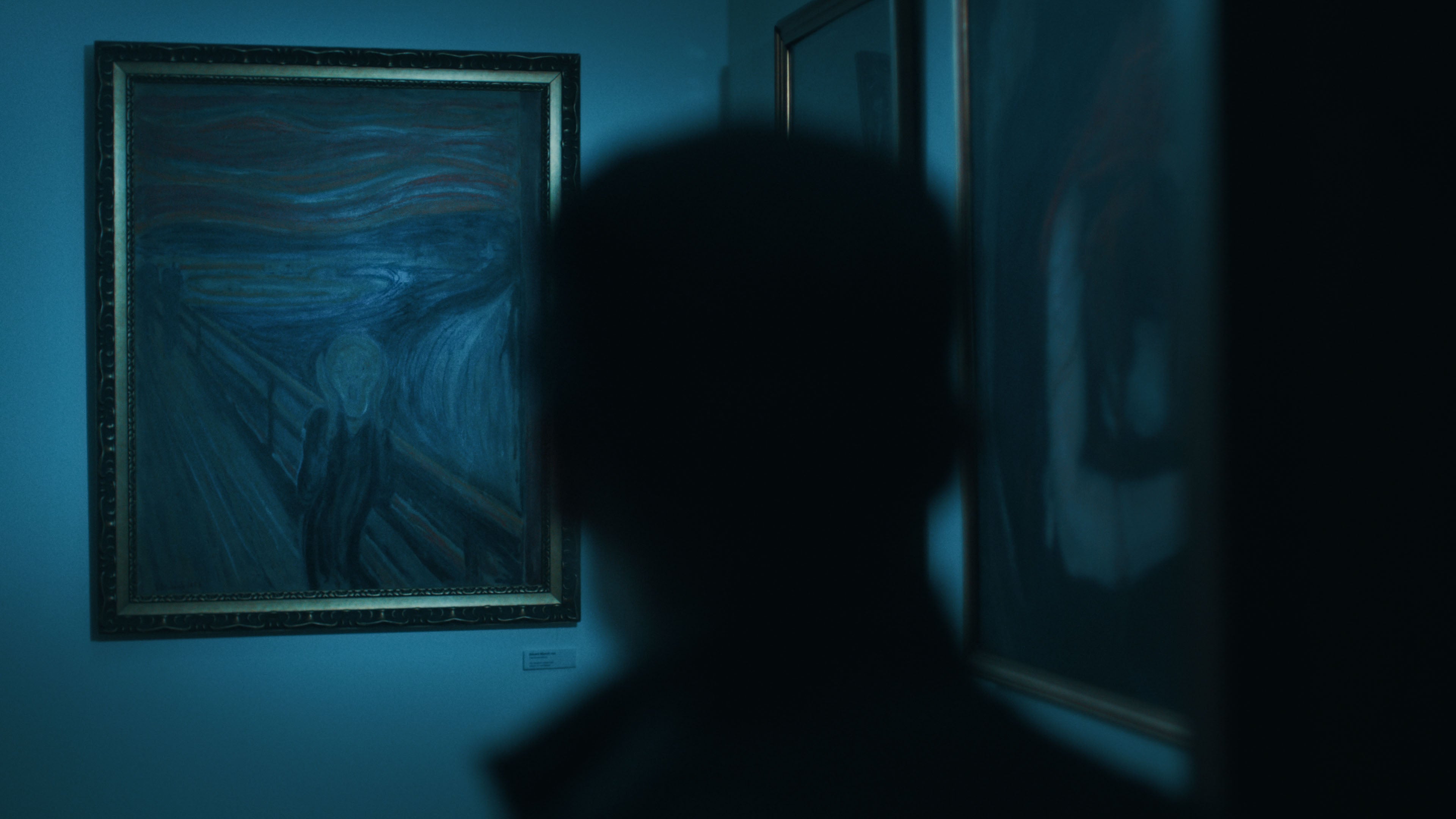

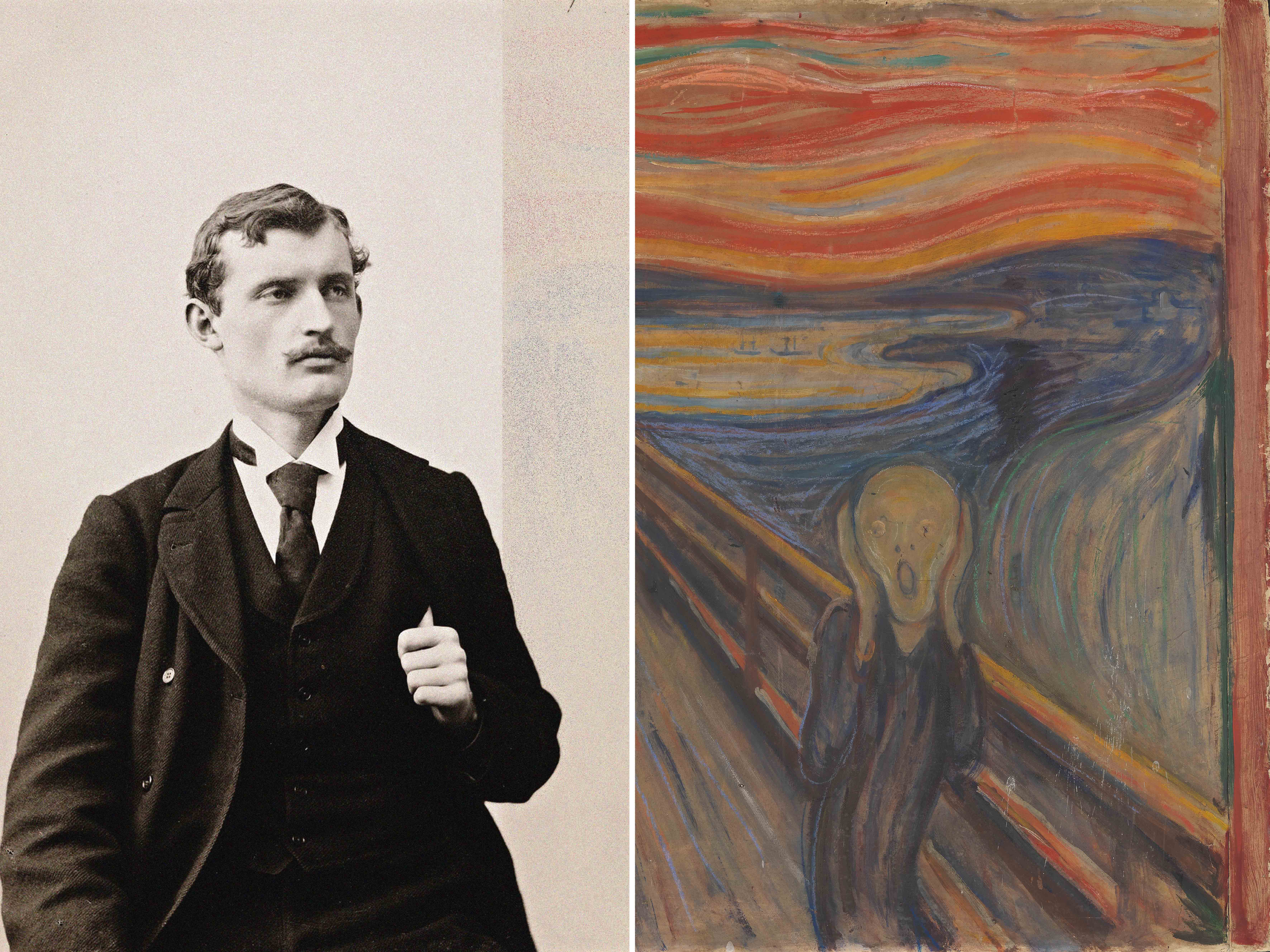

After tiring of playing football for Valerenga, the top club in Norway, he turned to crime, planning an apparently foolproof heist. He hired two homeless men to break into the National Gallery in Oslo and steal one of the most famous artworks in the world: The Scream by Edvard Munch.

The painting, whose iconic image of primal horror adorns millions of T-shirts across the planet, is so important, it is known as “Norway’s Mona Lisa”.

In just 90 seconds, the two thieves climbed a ladder, smashed through a first-floor window and took the world-famous picture with laughable ease. All the while, Enger stayed at home, ensuring he had a cast-iron alibi.

This has a good claim to being the most audacious heist of the last hundred years. The story has an almost unbelievable quality to it. If it were to be suggested at a Hollywood script conference, it would be laughed out of the room as utterly implausible.

This ludicrously flamboyant theft caused worldwide uproar and grabbed headlines all over the globe. Enger, who in 1988 had been jailed for stealing another Munch painting, The Vampire, which he had mistaken for The Scream, was the prime suspect. But he revelled in the global spotlight.

The boldness of his blag was only underlined by the fact that the day before it took place, Enger went out of his way to be filmed on the National Gallery CCTV so that, he says, “They would understand it was me, but couldn’t prove it.”

Enger exhibited even greater arrogance by leaving a note for the management at the scene of the crime. Scrawled on the back of a postcard depicting three people drinking beer that Enger had shamelessly purchased in the gallery shop were the simple words: “Thanks for the poor security.”

Nils Messel, the then curator of the National Gallery remembers that when he saw the postcard on the floor covered in broken glass, “My blood went cold.” Job done, then, as far as the master criminal was concerned.

Enger, who gives his own perhaps not always entirely reliable version of events in a gripping new documentary entitled The Man Who Stole The Scream, says, “The most important thing was to leave the card. That was my idea of fun.”

Now 56, Enger continues that he felt, “Untouchable. I was so sure of things. I had everything under control.” Brazen doesn’t even begin to cover it.

What motivated Enger to undertake this flashiest of crimes, then? The criminal, whom some might view as a fantasist, claims it was never about financial gain. “P. Enger means money in Norwegian, but money isn’t what drives me.”

Rather, he was propelled by an urge to say to the world, “Look at me!” He was determined to demonstrate to everyone that he was simply the best.

Enger says that even though by his mid-twenties he had enough money to buy two snooker halls and as many “blingy” cars and boats as he desired, “I wanted more. I always liked attention. I wanted fame. I most wanted to show the world I could pull off something huge. ‘Nice stunt’. That’s what I wanted.”

A natural showman, Enger was also pushed by a desire to outshine the competition. Clare Beavis, the producer of The Man Who Stole The Scream, says, “Pal was the Beckham of his time. He was the only footballer with a Porsche in the whole of Norway. Kids used to line up to watch him wash it. He was from the wrong side of the tracks, but he was a boy done good.

“His footballing idol was Diego Maradona, but when Pal felt that he couldn't play as well as Maradona, he went and did something else. His other idol was The Godfather – he loved all the mafia films. And so he thought he could be the Don Corleone of Norway.”

This most driven of men was also fuelled by a burning need to show off and emphasise that he was cleverer than everyone else. He very much enjoyed taunting the police and showing them up in public. He was eager to prove that he could easily outsmart them. “I always love to play games,” he confirms. "The stronger the opposition, the better I play.”

As an example, when he stole The Vampire, which was then worth £3.5 million, he concealed the picture in the ceiling of one of his snooker halls. Amazingly, the police would come in there every week to play pool, completely unaware of their proximity to this artistic gem.

Enger smiles as he recalls, “They didn’t know it was hanging one metre from them. They were so close, but they didn’t know it. That was the best feeling. We let them play for free just to have them there.”

After the police left, Enger would hang the painting on the wall and play pool next to it, chuckling to himself as he gloried in his superior intelligence.

Later, following the theft of The Scream, a painting that is literally priceless as it could never be sold on the open market, he would repeatedly phone the police. Masquerading as an anonymous caller, he would inform them that he had seen Enger driving around in a car full of stolen goods.

The police were so embarrassed about stopping him so often when he had nothing illicit on board that they left him alone, thereby allowing Enger subsequently to swan around unimpeded in a car stashed with contraband.

Enger even had the impudence to invite Gunnar Hultgreen, a crime reporter with Norway's leading newspaper Dagbladet, to take a photograph of him at the National Gallery in front of the space where the missing painting should have been. It appeared on the front page, heaping further ridicule on the police.

As Hultgreen puts it, “It was a way for him to say ‘ha ha ha’ to the police.”

Enger relished these taunts. “I felt I was taking it too far, but at the same time it was exactly what I wanted to do.”

When Enger had a son, Dagbladet announced that the baby had, “Arrived with a scream.”

“The police didn’t like it,” Hultgreen recollects. “He was saying, ‘I know that you know, but you can’t catch me’.”

Beavis observes, “Pal is the only criminal I've ever come across who wanted everyone to know that it was him who committed the crime. He wanted to show everyone that he was so clever that the police couldn't get him, even though they knew he had done it.”

So where did this desperate desire for recognition stem from? Sunshine Jackson, the director of The Man Who Stole The Scream, puts it down to Enger’s extremely troubled childhood; he was raised by an alcoholic single mother on a crime-ridden Oslo estate. “In common with so many people who did not get what they needed as children, Pal needed to be seen.

“His need to feel seen was really profound. He needed to be seen as the best footballer or the best criminal. He also needed to be seen by the police. He wanted them to say, ‘It was definitely him, but we can't get him.’ That's really common in people who were not the centre of their parents’ world and didn't have that loving home.”

The director adds, “He was obviously an incredibly challenging child. He used to climb up the outside of their 12-storey building. He really needed to fill that hole, but it’s a very big hole, and it has led him to do some very extreme things.”

Another element behind Enger’s craving to execute this most showy of crimes was his lifelong fixation with The Scream. “My obsession with this picture started the first time I saw it at the age of seven. We went on a school trip. As soon as I got close to the picture, I got an extraordinary feeling of anxiety and strange things happened in my head.

“I had such an intense connection with The Scream right away, and it’s never left me. I was obsessed with that painting long before I ever thought of stealing it.” From that moment, he would go to see it on his own three times a week for many years.

Enger goes on to outline why Munch’s howl of existential angst struck such a particular chord with him. “My stepfather was a wild guy. He hit me and my mother. He screamed so much at my mother all the time, I really wanted to... [He clasps his hands to the sides of his head]. I didn’t want to listen to that. I really wanted to hold my ears. It was myself I saw in the painting. I maybe felt other people have that, too.”

The abuse that he experienced at home clearly had an enormous impact on Enger. According to Jackson, “There is no child who has endured and witnessed domestic violence who is not profoundly affected by it. Pal was an extremely sensitive child. Inevitably, domestic violence exacts from the children who witness it a really, really terrible cost, no question.”

Beavis agrees that domestic violence helped to steer Enger down the road towards crime. When he was growing up, “Crime was never too far away. When you need that dopamine rush because you've not had that attention and that love from your family, crime provides a really powerful hit.”

Perhaps inevitably, even though he had run rings around the police for many months, Enger could not get away with the “perfect crime” indefinitely.

Under intense political pressure to recover Norway’s most renowned artwork and feeling humiliated by Enger’s very public derision, detectives encouraged gangland bosses to put the squeeze on him to confess to the theft of The Scream. Oslo criminals even went so far as to slash the throat of one of his best friends to force Enger to talk. But still he refused to spill the beans.

Eventually, though, the cat and mouse game came to an end when the Norwegian police recruited Scotland Yard’s fabled Art and Antiques squad to orchestrate an elaborate sting operation to catch the robber.

Charley Hill, an American Vietnam veteran working for Scotland Yard, was brought in as an undercover agent. He posed as an expert from the Getty, the richest art museum on the planet, looking to take the painting off Enger’s hands.

Hill knew that “You have to suck people into the trap. ‘Welcome to my parlour, said the spider to the fly’.” He soon succeeded in persuading Enger to hand over the painting in exchange for the promise of several thousand dollars, which obviously never materialised.

Himself a passionate art lover, Hill was able to verify the picture from the wax deposited on it when Munch had blown out a candle beside the painting.

At the subsequent trial in January 1996, Enger was found guilty and given a jail term of six years and three months – the longest ever sentence for theft handed down in Norway.

His trickery did not end there, however. He managed to flee from custody on a field trip in 1999. Enger was apprehended 12 days later wearing a blonde wig and dark sunglasses as he attempted to purchase a train ticket to Copenhagen.

Jackson reflects on what audiences might take away from The Man Who Stole The Scream. “I hope that they feel for Pal, as they are drawn into a world that they wouldn't normally inhabit. In our very polarised, black or white, right or wrong world, I hope people will understand why this crime was not as simple as it first appears.

“It wasn't committed because he wanted the money; it was a much more nuanced and complicated picture than that. I hope sitting in that grey area and empathising with somebody who is perhaps a challenge to our preconceived notions of what life should be like will help people take away from the documentary some of the complexity of the story.”

But in spite of his many setbacks, Enger’s bulletproof egotism appears undiminished. Referring to the theft of The Scream, he maintains, “One thing I like is that no one else gets sentenced for it and no one else gets credit for it. It’s my story, and that’s good.”

Other actors in this drama do not pass such a favourable judgement on him. Hill is especially harsh, asserting: “Forget what that self-serving son of a bitch thinks about himself. He stole the painting. He doesn’t deserve to have it. It deserves to be back where it is, where the people of Oslo and Norway and the rest of the world can appreciate it. Screw his sensitivities!”

Messel, who had to endure the indignity of finding Enger’s mocking postcard on the floor of the National Gallery, is equally damning. “Pal has no excuses at all. He was a hooligan and a thief. We can all be very obsessed with pictures, but we don’t go and steal them.”

There is one positive outcome for Enger, though. In prison, he learnt how to paint and has become a successful artist in Norway.

Beavis muses that, “Pal has used his art as a way of expressing himself. He’s had exhibitions, and he's sold paintings.”

What is the influence behind his art, then? “His paintings are, of course, all inspired by The Scream.”

‘The Man Who Stole The Scream’ premieres on Sky Documentaries on 19 August at 9pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments