Displacement utopia: How the Windrush generation revived Brixton’s cultural roots

In the aftermath of the Windrush scandal and ongoing gentrification, Genéa Saunders speaks to three generations of settlers who are united in keeping the area’s rich, vibrant culture alive

I have seen many changes around here throughout my time,” says Horace, known as Driver, 75. “The closing of shops, the changes to the market, the pubs – there’s no Blackman pub left, Atlantic Pub, George Berry, they’re all gone.”

Driver arrived from St Catherine, Jamaica, in 1961, to stay with his serviceman uncle who had returned to England in 1948 on HMT Empire Windrush after serving with the British forces in the Second World War. Living in Westbourne Park for a year, the then-17-year-old swapped the west London streets for Norwood, before settling in Brixton, which he has called home ever since.

In recent years, the terms gentrification and regeneration have become synonymous with south London suburbs such as Brixton. Known today for its farmers’ markets, pop-up restaurants, art galleries, delis, bars, cafes and vintage clothing stores, the area’s rich, cultural – and often chequered – history, has been all but forgotten. This is, after all, the hub of West Indian culture in the capital, with the Windrush generation right at its heart.

In the 1940s, this inner-city area, along with Peckham Rye, was once considered the shopping capital of south London, with three large department stores. Bombing during the Second World War lead to a mass housing clearance and the building of council houses. This would pave the way for the influx of Irish and West Indian immigrants, to call this area home.

Listening to Driver, it’s clear these independent pockets were the focal point for the black community to congregate, play dominoes and socialise with friends. He adds: “Everywhere you would go, you would know someone, there would be a face for you to speak with. Railton Road is what we call ‘front line’, it was like being back home. Music and chatter. You get all your hard food, you get your trunks, your material. It was nice.”

It’s clear that Driver holds on to the traditions from home. Perched in a corner of Windrush Square, he is smartly dressed, pleasantly enjoying the sun, music and vibrancy of the Windrush Day celebrations. “I’ve seen every single riot that’s taken place,” says Driver, “from Railton Road to Cherry Groce, but those days are done with – things have progressed since then.” While things have changed, Brixton still manages to keep hold of cultural roots.

In April 1981, Brixton was the scene of bloody violence and unrest following tension between the Metropolitan police and the black community, many of whom were now young second generation Windrush. Community anger came to a head when local Michael Bailey died in police custody having sustained a stab wounds prior to his arrest.

This, along with the increasing police presence and introduction of the “sus” law, where police could stop, search and potentially arrest on the basis of suspecting you were about to commit a crime, heightened tensions in the area. In early April, Operation Swamp saw more than 1,000 people arrested in six days. This was the final straw for residents. The media referred to the events that followed as “Bloody Saturday”, with nearly 300 police officers and over 60 residents injured.

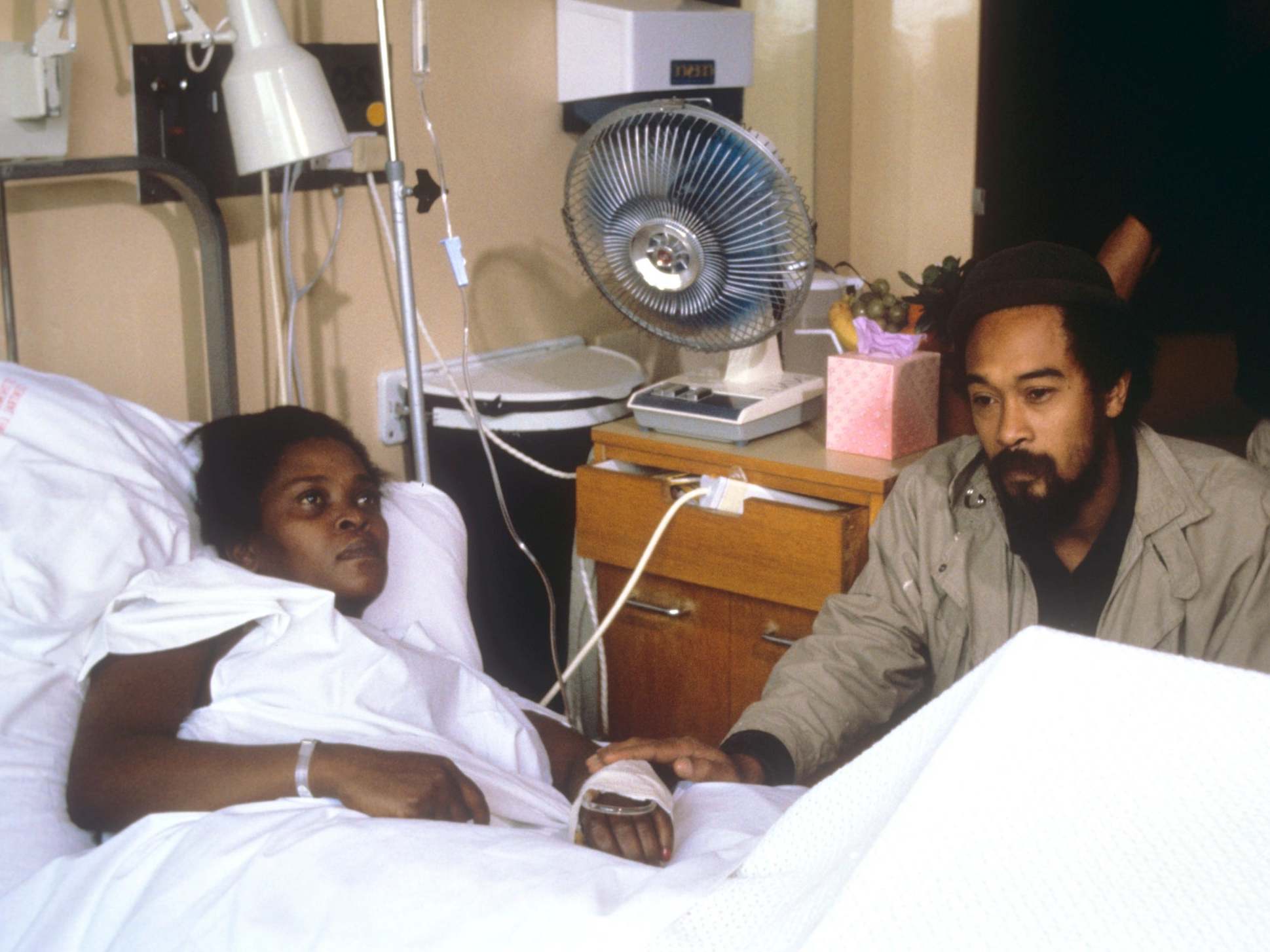

Four years later, in 1985, riots flared again when police shot Cherry Groce. Cherry was left paralysed from the waist down after police raided her home searching for her eldest son Michael in connection with an armed robbery. Inspector Douglas Lovelock shot Cherry after confusing the mother with her son, although Michael did not live there. This sparked the riots, during which photographer David Hodge killed by a brick to the head.

“Even though changes around here have pushed many black people out – the businesses at the side of the arches owned by Network Rail are gone, because of the increase in rent, they cannot afford it, and the same with the market on Electric Avenue, the people have gone – it has many different things now,” says Driver.

Although he believes that while the area will continue to change, the story of the Windrush will not be lost. “The third generation are not going to put up with what the first generation went through,” he adds. “So, things can’t get any worse. We have to live as one.”

Trevor, 36, from north London, knows all too well about the rapid changes that have forced many to embrace Brixton’s new image. “I’m not originally from Brixton, but I spent a lot of time down there as child,” he says. “My aunty lives here and as third generation Windrush I’ve witnessed the changes as a child and understand the implications as an adult.”

Trevor senses redevelopments in the area have become prohibitive for first and second West Indian generation residents, creating a barrier for togetherness. He says: “Things like Brixton Village, that’s not for your first or even second generation, as it was back then. The earlier generations now no longer have their spots, their hang out places, where they can frequent and come together.”

Market Row and Brixton Village (formerly Granville Arcade) were sold in 2007 to London & Associated Properties (LAP). The planned developments and changes to Granville row were considered to be the main arguments surrounding the gentrification debate within the area (this was cited as the start of residents feeling pushed out). However, LAP lost planning permission to remove existing buildings, including residential tower blocks and a private park.

In 2011 much of Brixton Village had been converted into cafes and restaurants, offering multicultural cuisines. Restaurant critic Jay Rayner listed it as “home to the most vibrant restaurant scene in London”.

Despite this, the market has not been without controversy. In 2015, more than 25,000 residents campaigned to save the closure of Brixton Arches, where more than 30 tenants and traders had been evicted after Network Rail increased the rent by 300 per cent to make way for new business services. The move was criticised by the SaveBrixton group as “destroying the markets that Brixton is known for”, adding “it’s pushing out local businesses and residents”.

In 2018, Brixton Blog reported that Brixton Market had been sold for £6,443,000 to American hedge fund firm Angelo Gordon. Referencing the changes in the social demography and the number of residents who had been “priced out”, Trevor says: “Brixton Village was put in place for what we see happening now.”

“Ten to 15 years ago it was easier to buy a house here, but now Brixton is diversified. If you haven’t been living here, you wouldn’t be able to,” he says. Having been fortunate enough to buy a property in the neighbouring area, Trevor says, “this is not the reality for many third generation Windrush people; house prices have tripled along with rent”, which makes the rapid changes a worrying prospect for the legacy of the West Indian community.

In 2016, Brixton Splash, a street festival that attracted tens of thousands of people, was cancelled after 10 years, with Lambeth council saying: “It costs too much to police and clear up afterwards.” While not an isolated issue – the trend has been popping up across many UK cities – Trevor insists that the arrival of new bars and “trendy hotspots” shouldn’t spell the end of community cultural events. “Brixton is a community with strong cultural ties and we as third generation have to ensure it continues alongside gentrification,” he adds.

However, not everyone agrees. Mavis, 87, who arrived in Brixton in 1955 from Barbados, believes Brixton’s transition is simply an urban regeneration no different to what was happening when she arrived.

“When we finally got to Brixton, it was horrible,” she says. “Buildings were in ruins, it was very dreary, but slowly you start to rebuild and revive the area.”

Mavis recalls how the increase in people migrating to the UK and settling in Brixton and its surrounding areas created an openness within the community. “Well, I’m a Bajan lady, you know. A big community from Barbados had made west London their home, but my husband was Jamaican, so we went to Brixton. But Brixton was becoming the place where even if you didn’t live there you travelled there for the community vibe, for all the things that you couldn’t get where you lived,” she says.

“Look, it’s no different today. People come here in search of that community spirit. The only difference is it’s people intrigued by West Indian culture, but they, too, just like us, want to put their stamp on things.”

The earlier generations now no longer have their spots, their hang out places, where they can frequent and come together

Since 2016, when nearly 17.5 million people voted for Brexit, change, migration, immigration, community and settlement have become big topics of discussion. There are clear parallels between Windrush, where thousands fell victim to Home Office rule changes that left them facing deportation, and concerns raised over today’s biggest influx of EU settlers, who could face a difficult road after Brexit to redeem a settled status.

Both groups have experienced growing concerns about change and belonging. Just like in the 1950s, where pockets of London became undeniably more West Indian, today pockets of London have become more European. The 2011 census revealed Haringey had the largest population of EU migrants, while a report by the Migration Advisory Committee in 2018 revealed no evidence that migration, despite all the concerns, was damaging people’s sense of belonging. Whether true or not, coexisting is something the Windrush generation seems to have personified.

In 2018, a political scandal hit the headlines when a Home Office review revealed thousands of Windrush children were denied legal rights and threatened with deportation. At least 164 people were wrongly deported or detained, who might have been made a resident before 1974, under the hostile environment policy. The anti-immigration policy introduced by Theresa May, then Home Secretary in 2012, was a bid to cut immigration numbers. But as a result more than 12,000 people found themselves affected by free movement, with many losing their jobs and homes.

Race and class inequality cannot be overlooked as one of the main drivers of discontent about gentrification. In the 1980s, Brixton was plagued by high unemployment, poor housing, police oppression and brutality towards young black men, which trickled into the 1990s. For long-term residents, these tales and scars are what make their area attractive to them, but it could once again be under threat unless they work together.

Steve Bentel, specialising in the cultural history of 20th-century London, says: “By the 1980s if you wanted to have a cool countercultural image of yourself and you lived in London, it helped to spend time in Brixton. Nightlife places, like the Fridge and the Academy drew people into Brixton for the night and exposed middle-class white residents to very limited glimpses of the West Indian community living there while at the same time. With some of the people becoming very interested in what they saw.”

Fast forward nearly 30 years, and not much has changed.

Joe Mckinnery, 36, moved to Brixton five years ago. “Chelsea was for the dickheads, Clapham was for the trendy, but Brixton had a cool, easy-going vibe, reflective of the people,” Mckinnery says, adding that while this influenced his decision, Brixton also provided the perfect commute. Located on the end of the Victoria line, it offers a good connection for hedge fund managers, investment bankers and financial officers working in Green Park and the surrounding areas. “Although I by no way have been here long in comparison to some of the community, I was here before Foxtons.” This, he says, was an indicator of “rising house prices” and the start of dispersal of West Indian families.

“Within three years I’ve seen house prices rocket from £365,000 to £700,000. This is attracting a certain individual, while allowing another individual to perhaps take advantage of a life-changing sum of money they would not have necessarily had before, which worryingly has the potential to change the essence and dynamic of what makes Brixton Brixton.”

Although data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) shows no change in the number of black residents between 2001 to 2011, it does reveal a rise in ethnic breakdown with mixed, Asian and other ethnic groups seeing a population rise – and “white British” bucking the trend, seeing a considerable decline.

Mckinnery and his neighbours have one common goal, which is to keep the area’s rich, vibrant culture alive – no matter the demographic changes to the area.

In 1998, the area in front of Brixton Tate library was renamed Windrush Square to recognise the important contribution of the African Caribbean community in Brixton, and marking the 50th anniversary of HMT Empire Windrush. Most recently, Windrush Square became the home to the UK’s new national memorial to African and Caribbean service personnel who fought in both the First and Second World Wars.

Prophet Slim, 40, who grew up in Camberwell, but spent much of his time in Brixton, is a true believer in preserving the legacy of Windrush and advocates for monuments like Windrush Square. At the Windrush: Looking Back, Moving Forward exhibition at the Black Cultural Archives (BCA), the UK’s only national heritage centre dedicated to the history of black people in Britain, Slim praises the work. He says: “It’s good to hold on to these types of things – it brings not only the teachings of the elderly to the next generation, but it’s the spirit of the people that brings this togetherness and unity.” He adds: “It doesn’t matter where they are, as long they’ve got spirit – their story will always be told.”

The notion of becoming and being one is apparent in everyone’s story, from Driver the West Indian settler, to Joe Mckinnery the gentrifier, to third-generation Trevor, to BCA, whose positioning statement states “we are one”.

In May it was revealed that architect David Adjaye would be designing a new building next to Brixton Market, which he describes as an “incredible opportunity to give back to the community”. The proposed design includes a new mixed-use building on Pope’s Road between the two railway lines by Brixton Station, which will provide community space on the ground floor and an opportunity to extend Brixton Market. Speaking about the plans, Adjaye told Architects’ Journal: “This project fits into a narrative that is incredibly important to me, making civic and social spaces that are about bringing in diverse constituents both locally and from the city and its visitors.’’

He said it would be “socially constructed architecture that can edify the community. When taking on this project, I could see the incredible opportunity it had to elevate the experience and give back to the community”.

You can only hope this is something that will truly capture the residents of Brixton, particularly the Windrush generation, who along with the Irish community, have helped to revive this area into the Brixton we know today, creating the foundations for displacement utopia.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments