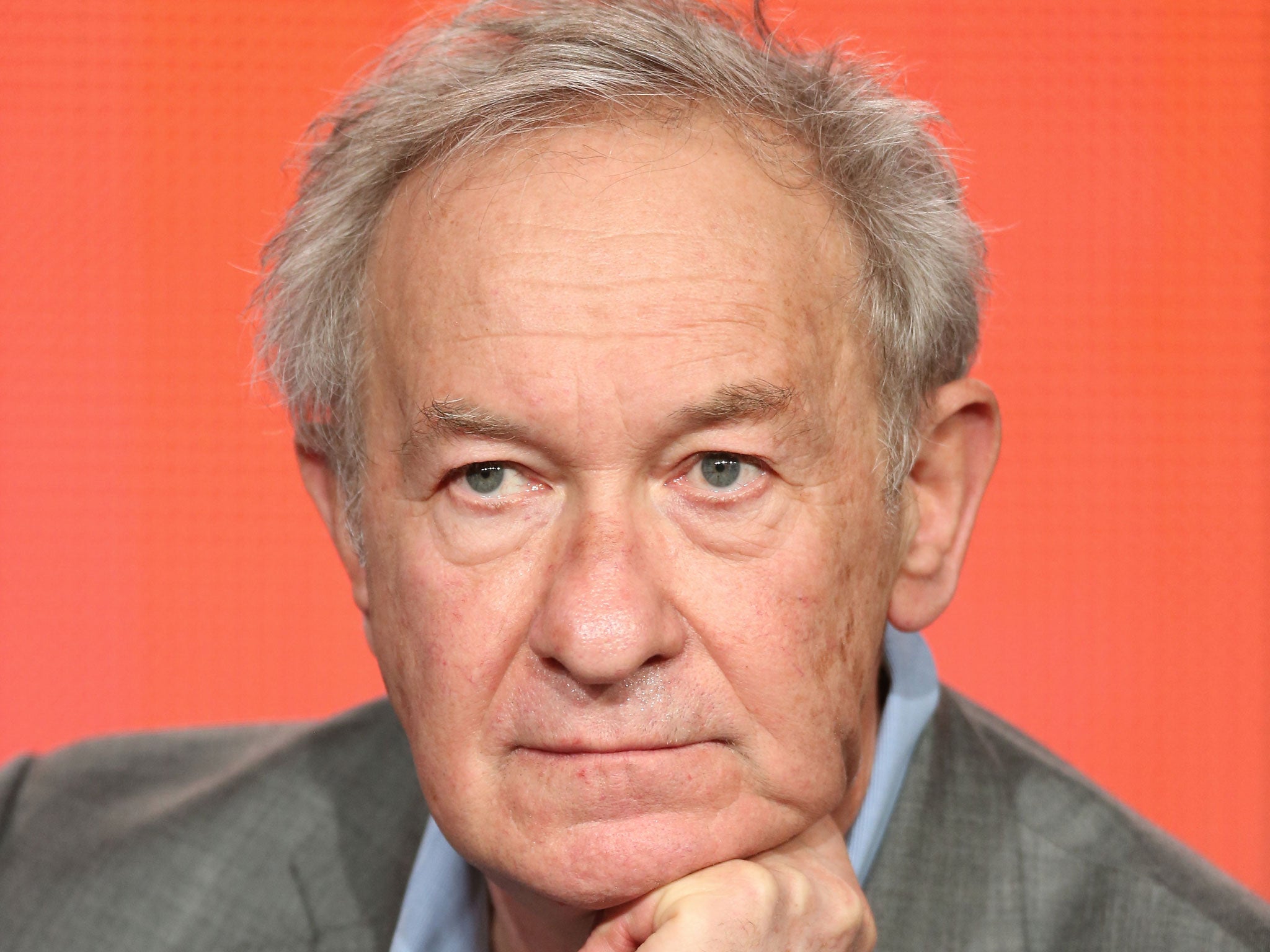

The Obliterators, review: Simon Schama gives the horror of war a human face

In the Radio 4 documentary about iconoclasm in Syria and Iraq, Schama's anger was directed at the smashing, bulldozing and looting of precious antiquities

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."It's been a bad year in that part of the Middle East we refer to, without irony, as the Cradle of Civilisation," said Simon Schama in Radio 4's The Obliterators, to the sound of exploding masonry and shattering glass.

There was nothing casual or objective about the historian's introduction to this documentary about iconoclasm in Syria and Iraq, and nor did you expect there to be. Schama is best known for gliding around draughty castles and historic houses dishing the dirt on dead aristos on television. But lately he's been more concerned about contemporary events.

Here his anger was directed at the smashing, bulldozing and looting of precious antiquities "on a scale unprecedented in modern times, and certainly the largest mass destruction of cultural heritage since the Second World War".

It's hard, right now, to feel much more than a defeated sadness at the seemingly petulant actions of Isis militants towards Middle Eastern treasures when one looks at aerial shots of the war-ravaged Aleppo, or hears about the starving residents of the besieged town of Madaya, or the scores of refugees still drowning at sea.

But Schama was careful to acknowledge the terrible human toll of the Syrian conflict. He also pointed to the heartbreak felt by local people at the destruction of their heritage, and those who have risked their lives trying to remove what they can before the arrival of Islamic State.

Among those trying to salvage smaller, more mobile items was 82-year-old Khaled al-Asaad, a scholar in Islamic art and the former director of antiquities in Palmyra. Last summer, refusing to reveal where the rescued antiquities had been hidden, he was beheaded outside the town's museum.

Schama was keen to get into the mindset of a jihadi who wilfully demolishes his own history. He spoke to Dr Usama Hasan, a part-time imam and senior researcher in Islamic Studies at the Quilliam Foundation, who observed the "puritanical fringe insistent on wiping out what they see as idolatry, even if ancient statues and idols are not being worshipped any more. They haven't realised that such ancient sites are of immense historical and spiritual education. There's really no need to get iconoclastic about it."

Schama also drew parallels with the Protestant Reformation in England in the 16th and 17th centuries, a period of "state-sponsored assault" on images that were equated with idolatry. He looked at historical precedent, changing belief systems, the nature of theological radicalism and the human desire to replace old with new, and in some cases to dispense with the past entirely.

None of this was meant to excuse the actions of Isis, merely to put them into broader context. This was Schama at his best: assertive, reflective, utterly righteous, and able to make you look differently, if not sympathetically, at the folly of humankind.

Over the past few days, Today has run a series of extraordinary audio diaries from a Syrian activist about life under Isis in the city of Raqqa.

Here his name was changed and the voice of an actor used to protect his identity. His testimony, in which he recounted being flogged for cursing in the street, watching neighbours being robbed at gunpoint by soldiers, and witnessing public executions for the smallest of infractions, was chilling, vital listening.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments