Radio review: Archive on 4 - now we know how to make a train robbery 'great'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

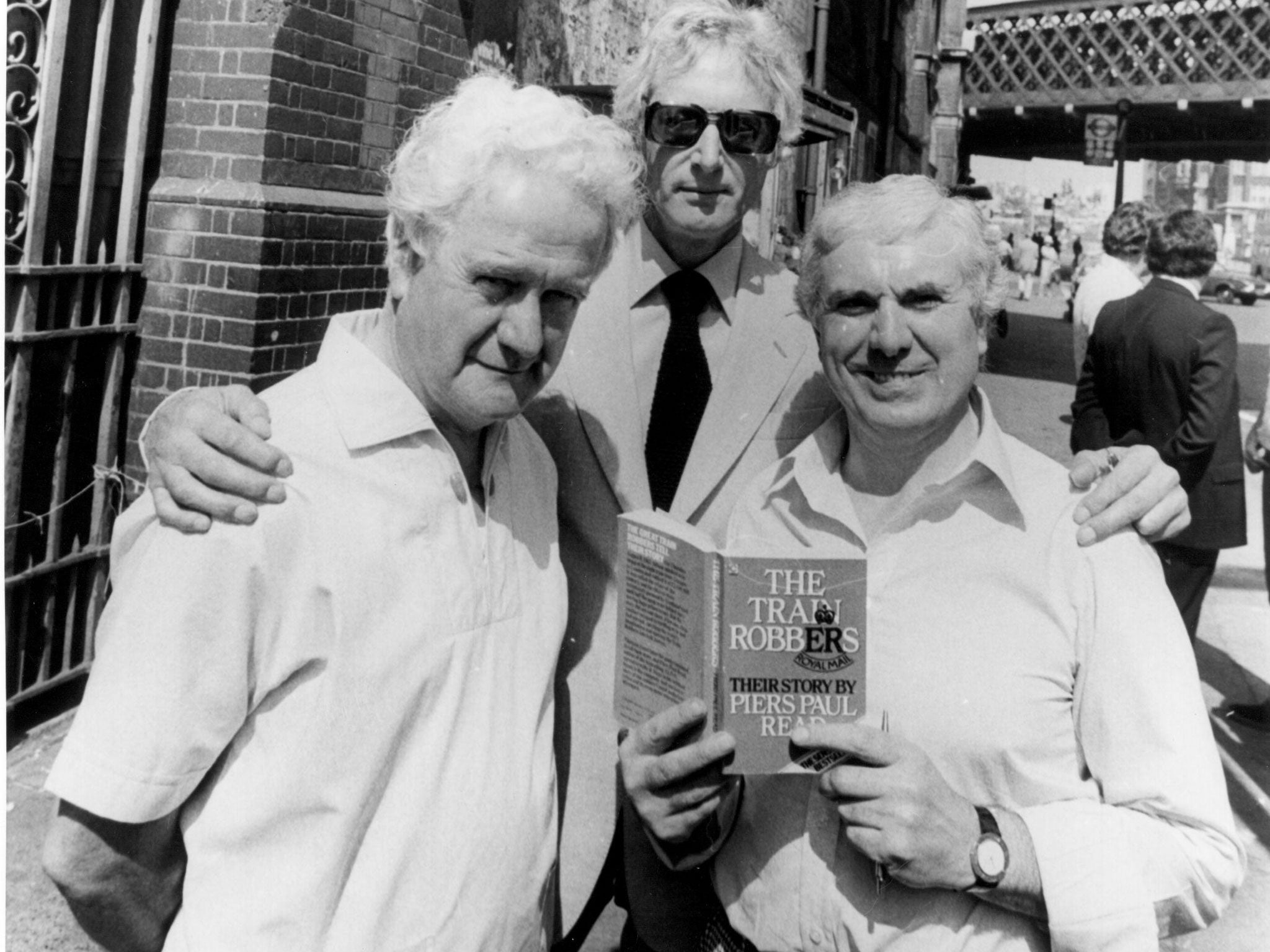

Your support makes all the difference.I wonder who first applied the adjective “great” to the term “train robbery”? A sub-editor on the Mirror or Express, I imagine. He or she might well have intended it to describe size rather than worth, but it’s a sign of how we remain titillated by the events of half a century ago.

Jake Arnott’s novel The Long Firm drew on the Krays, for whom we also retain a strange fascination. This made him the ideal person to explore why, as he put it, the Great Train Robbery “still occupies a significant place in the British psyche”, and it made The Crime of the Century a terrific contribution to Archive on 4.

Laurie Taylor, sociologist and Radio 4 stalwart, led the “lovable rogues” lobby. He’d taught robbery ringleader Bruce Reynolds at Durham nick, and rather liked him. “The governor said, ‘don’t be taken in by all that suave charm’ – I was a bit.” Arnott interviewed Reynolds before he died in February, and was struck by his “elegance and panache”.

John O’Connor, former head of the Sweeney (Flying Squad), got to the heart of why Reynolds and Co are part of folk history. “The mood was rebellious,” he said. “People were pleased when the establishment got a bloody nose, and that’s understandable. There was a lot of poverty about – I’m not surprised they were looking for working-class heroes.”

Whether hero or villain, Reynolds – as seemed fitting, as he was clearly intelligent and articulate – had the best line. “I wanted to live a life like Hemingway,” he said. And, in his own way, you could say that he did.

In The Unsent Letters of Erik Satie Alistair McGowan, a Satie obsessive, explored the composer’s singular private life (he had short, tempestuous affair with the artist Suzanne Valadon then was celibate for the rest of his life). The title was a bit of a tease, as the letters were sent to Valadon after he died. She read them then burned them. One survives, and awful, self-pitying guff it is, too.

When Satie died his tiny flat contained, apart from the letters, mounds of newspapers, two grand pianos, one on top of the other, every bill he’d ever been sent, unopened, six identical suits and 144 white shirt collars. He’d have been a shoo-in for one of those mad-hoarder shows.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments