Last Night's TV - Double Agent: the Eddie Chapman Story, BBC2; Imagine: Alan Ayckbourn – Greetings from Scarborough, BBC1

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Double Agent: the Eddie Chapman Story looked as if it had dramatically raised the bar with regard to what presenters are expected to do to bring a story to life.

Something of an inflationary spiral was already in place before this film. Whereas it was once felt enough to stick your man or woman in an appropriate geographical location and have them walk towards the camera waving their arms, viewers now expect more. We want to see our presenters in a yacht, or on horseback, or driving an open-top car as they deliver their lines. Double Agent included at least two of those, but the producers of Ben Macintyre's very entertaining film about Agent Zigzag hadn't stopped there.

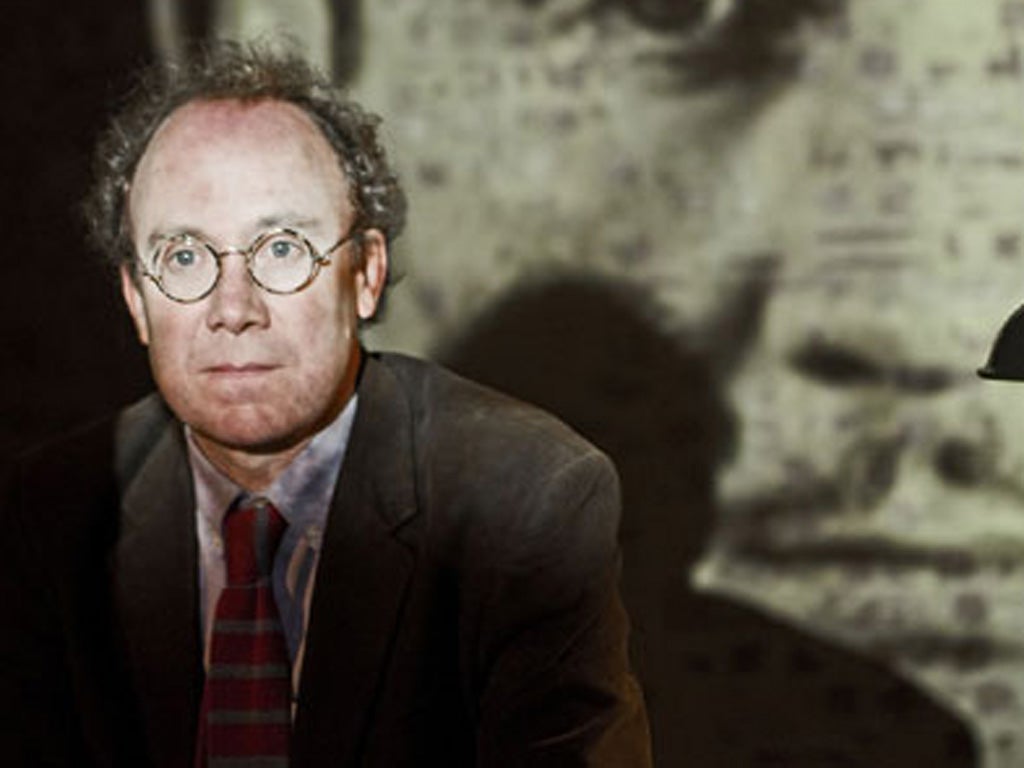

They'd gone on to introduce the novel idea of the stunt presenter. In the interests of his story, Macintyre crouched next to a safe as its door was blown off (he looked genuinely apprehensive at that point), did a parachute jump from a wartime transport plane and leapt through a glass window. Or at least he appeared to, since he makes a slightly unlikely action hero – a bespectacled man with scholar's hair and a genial expression. If he were ever to sustain an injury in the course of his work, you feel, it would more likely involve a dropped book in the London Library than a night drop over enemy territory.

He does tell a good yarn, though, and this one was excellent, the story of a pre-war safe-cracker with an eye for the main chance. In the spring of 1939, Eddie Chapman was wanted on more than 40 charges of robbery, having made it his business to spare Odeon cinemas from the job of carrying the box-office take to the bank. After a robbery went wrong and Chapman was arrested, he jumped bail and fled to the Channel Islands, where he was recaptured. When the Germans invaded he was locked in the island jail and promptly offered to spy for them as a way of getting out. Since the Germans weren't having a lot of luck with their British agents at the time, they took him up on his offer, and released him for training at a spy school in Nantes. What Eddie lacked in moral rigour he more than made up in flair and cheekiness. He purchased a pet pig, called Bobby, and took him for walks in the local woods, a fact that led to some puzzlement back in England, where the code-breakers were regularly deciphering Chapman's test transmissions. Even Bletchley Park's finest brains were stumped by, "Your friend Bobby is growing fatter every day. He's gorging like a king, roars like a lion and shits like an elephant."

Chapman's first call after landing in a Norfolk field was to the police, and, after interrogation by a monocled intelligence officer called "Tin Eye" Stephens (it's a feature of this tale that you wouldn't dare make up most of the details), an elaborate deception operation was set up so that Chapman would appear to have sabotaged a Hendon aircraft factory. Then, astonishingly, he agreed to go back to Europe, where he was awarded an Iron Cross and lived the high life in occupied Norway, before returning to England to help deceive the Germans about the targeting of V-1 bombs. He can't have been entirely a scoundrel, because he was revealed by an archive interview to have been an early reader of this newspaper, but if he was ever motivated by anything other than greed and self-interest no compelling evidence for it was supplied here. Terrific tale, though, and very amusing action scenes from its presenter.

Alan Ayckbourn voiced a heresy in Imagine's profile of the playwright. He was imagining his response to Scarborough day-trippers who feared that the theatre might be beyond them. "You watch much more difficult things on television every day of your life," he countered. Not every day perhaps, but more often than most theatre types would be prepared to admit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments