TV Review, The Rise and Fall of Nokia Mobile (BBC4): How the Finnish firm called it

Before Apple there was only one mobile phone connecting people: this is how they did it. Plus, out of Africa... the story of the continent’s great civilisations before Europe started meddling

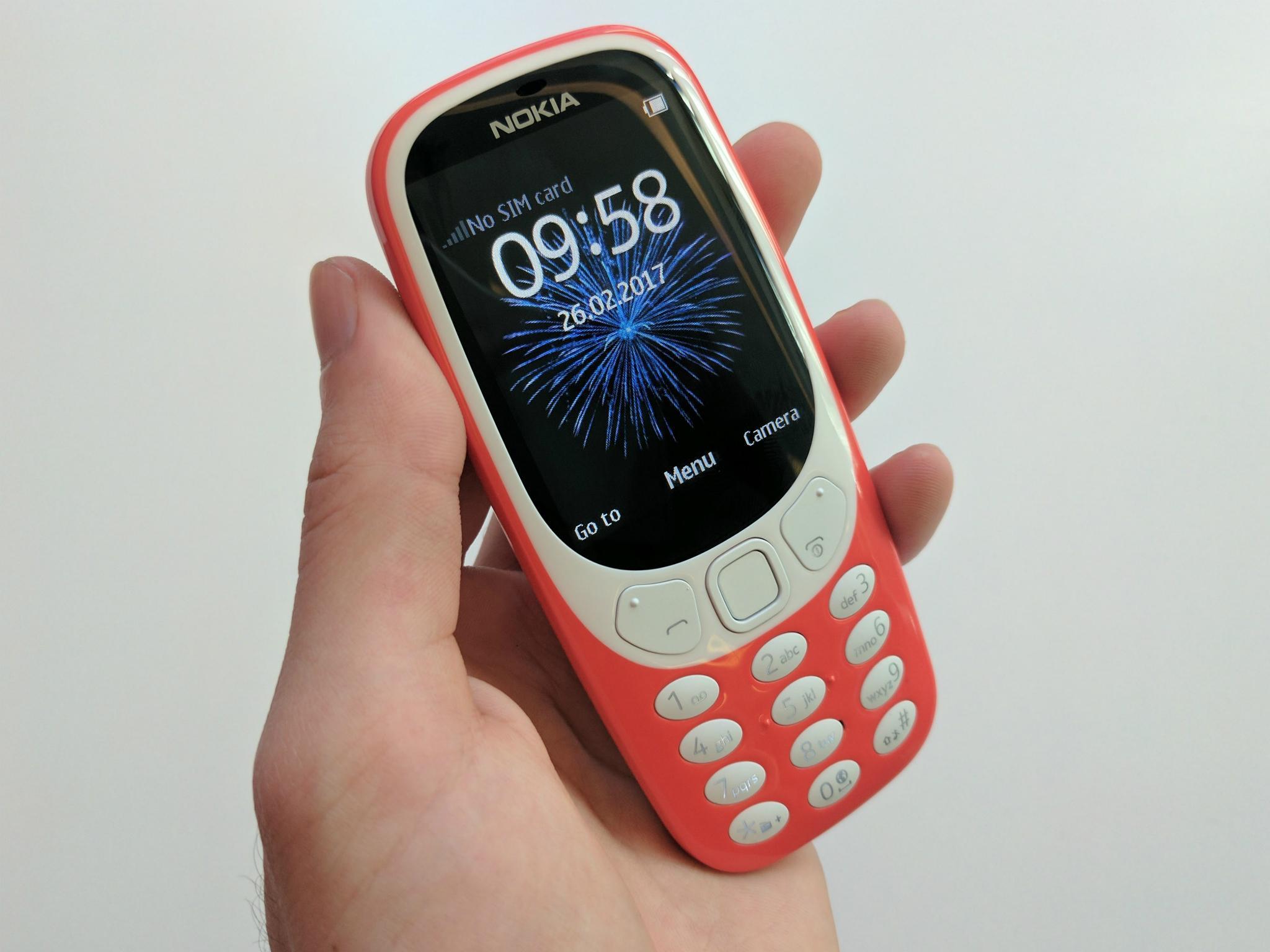

What went wrong for Nokia? Nokia Mobile was for 14 years the world’s largest manufacturer of mobile phones, a pioneer of the technology that has transformed the world. Now, if anything, it is a mere badge on other people’s operating systems and products, often now relegated to ironic retro designs.

The prior question, answered equally satisfactorily in BBC4’s The Rise and Fall of Nokia, would be: what went right for Nokia?

A pulp mill founded in Finland in 1865, the company wasn’t an obvious contender for global leadership. Its pre-eminence derived partly from one of its hobbyist bosses, Jorma Nieminen, the “father” of the Finnish mobile phone industry, extending his boyhood interest in radios. In Finland there was also a ready demand for this nascent technology, being a sparsely populated nation with relatively few fixed lines. People wanted to make calls when they went to the lake on their boat or stayed in their holiday cottage – or if there were some emergency on the move in their beautiful but inhospitable land. Serendipity.

By 1972 some 1,600 mobile phones had been manufactured, and 20 employees made these exotic behemoths. These promising machines started to generate interest. The story was told of a chap, rather ahead of his time, who took his family to the zoo for the day but could not bear to be out of contact. So he carried his “phone” – a suitcase with 13kg of primitive electronics – all day around the ape house, through the aquarium, to meet the tapirs … No one rang.

No matter for Nokia. They pressed on. They were the first to offer a commercial handset for text messages; the first to offer, albeit crude, web access; the first to allow users to download ringtones (Crazy Frog); first to make a phone a calendar and a calculator; and the first to fit a game (Snake – remember that?), thus turning the mobile phone from a device to raise productivity into one that lowers it.

Like Lego, Ikea and Volvo, Nokia was infused with a proud and distinct Nordic business culture – open, cooperative, creative and technically driven. But that culture did not survive the growth of Nokia into a vast multinational company; one that even had a phone factory in China that made not a single phone, forgotten by HQ back in Finland, built just to keep the local provincial Chinese authorities happy.

Like an old mobile with a dodgy keypad, the culture had malfunctioned. According to insiders, people were recruited who “cared only about the money, [share] options, company cars and wages”. Teams no longer collaborated instinctively. One phone had buttons that didn’t do anything because the designers hadn’t spoken to the marketeers. Nokia’s slogan of “Connecting People” turned ironic.

None of that would have mattered so much if the Apple iPhone hadn’t arrived on 9 January 2007. But it did; computing and phone techs converging. Terrified, Nokia ordered dozens in. One exec took his iPhone home. When his five-year-old daughter asked daddy, “Can I keep the magic phone under the pillow?” he knew they’d had it.

Was that inevitable? There was an intriguing interview with a Finnish inventor named Johannes Vaananen who said that his “MyDevice” had the first finger swipe function, a full-on web browser and autocorrect – years before Apple. When he took his prototype to Nokia they called it a “gimmick”. In due course Apple acquired some of the patents.

He himself thinks it would actually have been unbelievable if Nokia has just gone ahead and made his proto-smartphone on his say-so, and Nokia were not the only firm who turned him down. Nor was Nokia entirely mad to believe that people would not tolerate a phone, such as Apple’s, where the battery only lasts a day and which will shatter if dropped on the road.

So there was nothing predetermined about the fall, nor the ascent, of Nokia. There were known external forces as well as a varying quality of management at work – but also sheer luck, on the way up and on the way down. In other words, just as mafia bosses are said to apologise before they “whack” a competitor, Nokia’s decline at the hands of Apple was “just business”. A shame, all the same.

I was sad to watch the sun set on Henry Louis Gates’s Africa’s Great Civilisations, an imperial grade television history show. He finished up with the “scramble for Africa”, whereby the European colonial powers carved up the continent for their own purposes, so that by 1900 only a proud Ethiopia was left independent. They, alone, had seen off the Europeans (Italians as it happens) and showed, at Adowa in 1896, they could be beaten – provided you, like they, had machine guns.

We were also taken through the cruelties imposed by King Leopold II of the Belgians on what was for a long time his personal property – today’s Congo, a territory rich in natural resources such as copper, rubber and ivory. Leopold’s rule was so brutal that his agents would amputate the limbs of children who failed to fulfil their quota for rubber production. It rendered grotesque, even at the time, the Europeans’ claim that they had turned up to “civilise” Africa. So did the blatant exploitation by the likes of Cecil Rhodes in the diamond and gold belts of southern Africa. All of these episodes sowed the seeds of later liberation struggles, and post-liberation troubles. We need more of Gates’s insights into yesterday’s (which is to say today’s) world. Maybe he could “do” the Americas?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks