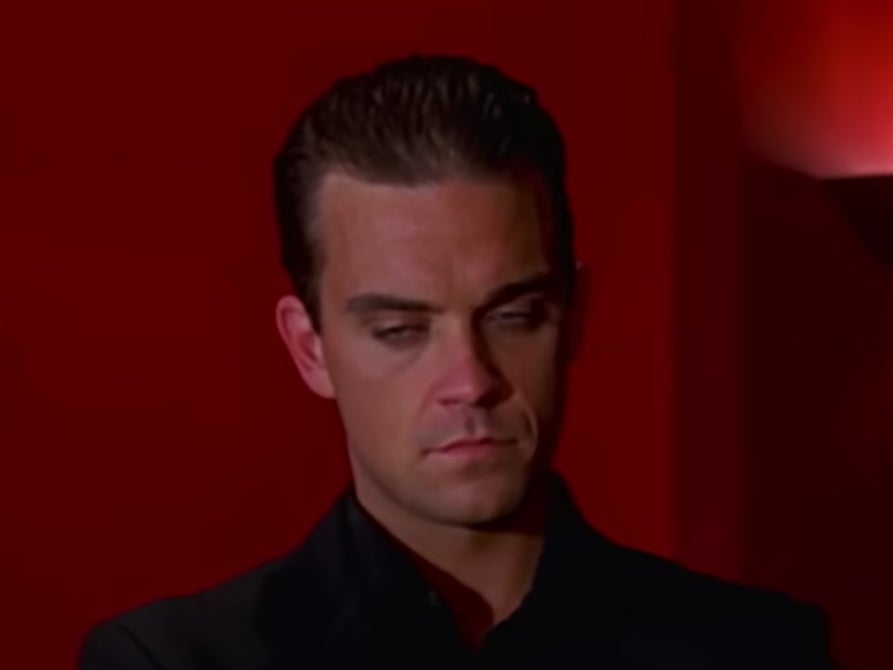

Robbie Williams opens up about his mental health struggles and ‘biggest career regret’

Exclusive: The singer discusses his new tell-all Netflix documentary, which chronicles his rise to fame and ensuing mental health struggles, and gets candid about his career

Robbie Williams has opened up about his history of mental illness and self-harming in a frank discussion ahead of a new documentary chronicling his life, along with sharing what he regrets most in his career.

The four-part series, simply titled Robbie Williams, sees the “Angels” and “Let Me Entertain You” singer provide commentary as he watches footage from the early 1990s right through to the 2010s, showcasing his stratospheric rise to fame and the numerous obstacles he faced as a result of his struggles with depression and addiction.

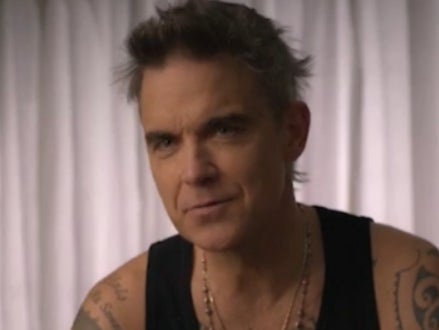

“As humans, nobody likes looking at photographs of themselves and no one likes hearing their own voice, so if you multiply that by watching yourself suffer with mental illness, breakdowns, alcoholism, depression, [and] agoraphobia, you’re in a tortuous headlock where you’re forced to watch the car crash in slo-mo,” the singer tells The Independent. He wryly adds: “It’s all right – it’s gonna work out for me.”

Williams, 49, describes making the documentary as “traumatic”, adding: “I hope it is for the viewer, too.” In fact, to psych himself up for the shoot, which took place in his bedroom, the singer came up with a new song, the lyrics of which go: “Trauma watch, trauma watch, come and watch me have a trauma watch.”

In the 1990s, Williams, who hails from Stoke-on-Trent, successfully embarked on a solo career after leaving boyband Take That. He achieved what, on paper, every musician would consider the pinnacle: record-breaking success that led to him matching UK chart records previously held by Elvis Presley, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. However, he was struggling internally and, because he was “box office” in the eyes of tabloids, what should have been occurring behind closed doors found its way onto the front pages.

“It’s very difficult for people to understand the psychology of this great gift that has been given to you but yet it’s breaking you,” Williams explains. “Up to now, mental health was talked about in a different way. It was very confusing for people who went, ‘All he’s gotta do is get up and sing another song. Give him a nudge or else we’ll lose all the money.’ What should have happened is, ‘Get in a car, we’ll just go get better.’ But it didn’t, and it’s OK ’cause I lived to tell the tale. It makes life’s tapestry richer, I suppose.”

One detail omitted from the documentary is an incident when Williams referred to an act of self-harm. He gets onto this subject following a question about whether he has contacted Lewis Capaldi in the wake of the singer’s decision to postpone all dates after becoming overcome by tics during a Glastonbury 2023 set. Williams says he has.

There’s nothing sexy about taking a knife and slashing your own wrists, which I did

“There’s nothing sexy about [self harm],” he says. “I remember in the Nineties, when I tried to talk about what was going on with me, I was berated and belittled and told to pull my socks up. What that does is isolate you even more. I know celebs are celebs, but they’re people, too.”

When asked to clarify the comments he had made about self-harming, Williams told reporters: “The reason I say that is to qualify that people are people. Whether they’re on MAFS [Married at First Sight] or in Martin Scorsese’s new film, we better be careful how and what we accuse people of, or say what we think of them when it comes to their own mental illnesses. I haven’t had a drink for 24 years and I haven’t done drugs for a decade or so. There’s a reason people stop: because they’re in hell.”

The documentary shines a spotlight on Williams’s fractured relationships with key figures from different chapters of his life: his former Take That bandmate Gary Barlow, his ex-girlfriend Geri Halliwell, and songwriter Guy Chambers, with whom he enjoyed huge success until they parted ways in 2002. I ask whether he consulted with any of them ahead of, during or after production.

“No, because legally I didn’t have to,” he replies. However, he says, “When it comes to the biopic [the forthcoming Better Man, directed by The Greatest Showman’s Michael Gracey], I’ve had to have chats there, yeah, and they are uncomfortable. The chats have been uncomfortable. Needless to say, when the biopic was being made, there were several c***s in that film. Now there’s only one – it’s me.”

In terms of regrets, there is one that rests at the forefront of Williams’s mind: the panned song “Rudebox”, which was the title track from his divisive 2006 album.

“I think what happened with that album is, for the first time, I was having real, proper fun making a record. There was no professional business about it and it was silly and full of humour and I thought, ‘People are going to love this ’cause I’m being me for the first time.’ I should have put it out third and explained properly: ‘It’s daft, I know! I’m not trying to be a grime artist – let’s all laugh together!’”

He says “the biggest cringe point” for him in the documentary “is when I explain to an audience that are about to listen to ‘Rudebox’ for the first time that this is going to be the biggest single since ‘Angels’.”

People started filming me when I was 16 and they never stopped – I don’t f***ing know why

Making the documentary has also been a time for Williams to be particularly introspective about his fame. “People started filming me when I was 16 and they never stopped,” he says, adding: “I don’t f***Ing know why; I didn’t ask them to.” He also says he’s “not a musician” but “an entertainer who writes some songs”, and believes that, if he was a teenager today, he’d probably have “become a content creator” instead of one of the country’s biggest pop stars.

Still, he’s happy with his lot, and is very much aware of the extent of his success. “What I’ve done is the equivalent of stretching an elastic band from Stoke to Mars, when it comes to my talents and where I’ve found myself. And I’ve sold the most No 1s in the UK ever: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Elvis and me – that wasn’t supposed to f***ing happen. And I say that in a way like I’m as dumbfounded as anybody else.”

Williams has also been happily married to Ayda Field since 2010, and the couple have four children, one of whom, 11-year-old daughter Teddy, appears in the documentary. But while he says his mental health is “better than it ever was”, he “refused” to give Netflix producers the catharsis they desired for the final episode.

“I think that was the narrative, and the last day was five hours of them trying to get that out of me. I was like, ‘That’s not how I f***ing feel!’ I know for the last four weeks, I’ve been out of the headlock and been having a really nice time, but who knows what happens. I’m not bipolar, but there is a sort of semi-bipolaresque element to my mental health. Some days good, some days bad – but it’s better than it ever was in the 1990s and at the start of this century.”

‘Robbie Williams’ will be released on Netflix on 8 November.

If you are experiencing feelings of distress and isolation, or are struggling to cope, The Samaritans offers support; you can speak to someone for free over the phone, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

You can also contact the following organisations for support: actiononaddiction.org.uk, mind.org.uk, nhs.uk/livewell/mentalhealth, mentalhealth.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks