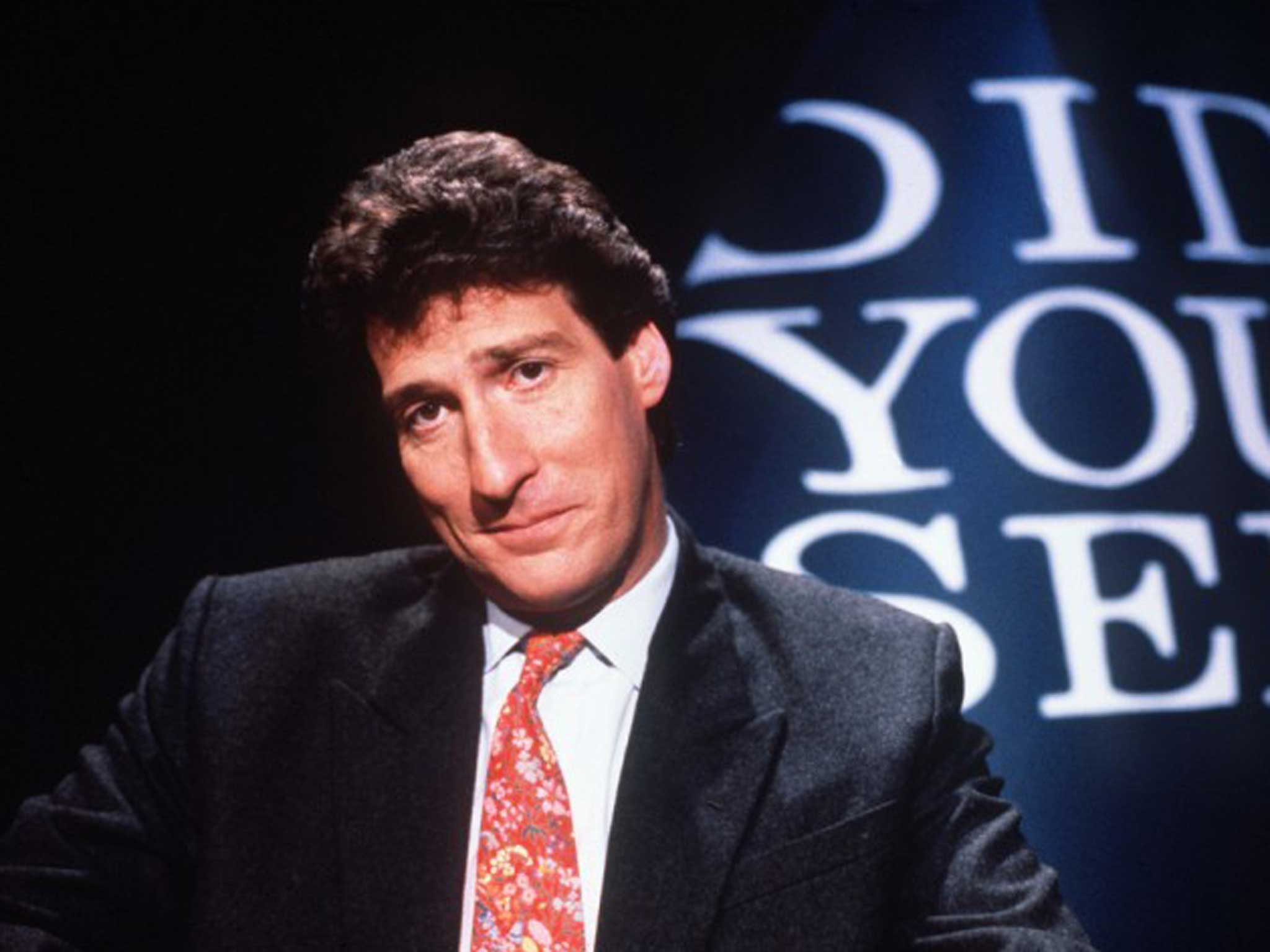

Jeremy Paxman leaves Newsnight: The Big Beast interrogation will never be quite the same

He made performative contempt his own, and imitators are doomed to failure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There's a YouTube clip of Jeremy Paxman presenting the BBC's Breakfast Time in about 1988. The footage is from a behind-the-scenes documentary, and everything is going horribly wrong: an expected guest, the actress Susan Hampshire, has failed to turn up, and the producers are wondering how on earth they're going to fill the gap.

As they frantically juggle their options, Paxman – whose co-presenter is Kirsty Wark – can be heard booming away in the background. "Don't you have any respect for the fact that he's clearly managing the economy?" he asks a shadow minister. "His balance of payments forecast is about three times less than it was the last time we had a Labour government." "Well it's not, actually," the politician answers, plainly a bit irked by his interlocutor's tone. It's an up-and-comer called Tony Blair, and the face-off obviously makes for good television. The producers have a rethink. "We might not need Susan Hampshire," one says. "Let it run."

More than a quarter of a century later, Paxman still makes for great television. But he is, in some ways, a different beast today. His ties have improved. Instead of a jet-black bouffant, he has an expensive-looking silver crop. His impeccably received pronunciation has shifted subtly down the social scale. (In a clip from his first year on Newsnight, it's a treat to hear him pronounce "again" to rhyme with "rain" instead of "men".) And in the past few years there has been another noticeable shift – if not in the incredulous tone, then in the frequency with which it is adopted. No one is immune. He was always a sceptic, but of late, his ever-arching eyebrows and exhortations to "come on" seem to suggest he might have become a cynic, instead.

This has happened as he has ascended to the very uppermost tier of the media hierarchy, and it's hard to tell which is cause and which effect. The grander he has become, the more determined he has been to let us know that he hates it. We love it, of course. It's the final act of a gangster movie, in which our street-brawling hero is seen reluctantly navigating the boardroom. The setting isn't promising, but even the dullest meeting is enlivened when you notice that one of the participants is wearing a knuckleduster.

Those movies tend, too, to feature a scene in which the protagonist reflects on what he has wrought, and wonders whether it was worth it. And now that he's leaving Newsnight, the same question presents itself with Paxman. In his case, the answer is complicated. If he has become a slight pantomime of himself in recent years, he still seems an almost unmatched interrogator of people and ideas alike, never so wrapped up in personal animosity for his sparring partner that he is unable to see the larger point, always alive to the guard-lowering power of the unexpected question. His performative contempt can get a little wearing, but he has never developed the fusty grandfatherliness that afflicted John Humphrys (only seven years his senior), mostly because he's much funnier.

And yet there's an ambiguity to his legacy. That approach – "why is this lying bastard lying to me", as he so famously put it – works because he is a truly Big Beast, with one of those faces, like Blair's, that has become so familiar and so imposing that you can no longer tell if it's handsome or not. He is convincing when he treats even the grandest politician as an equal, and sufficiently intimidating for most of the rest that his mere presence can turn the best-briefed lines to a dry-mouthed chaos. (Poor Chloe Smith.) You don't lie to Paxman if you can help it, and so usually, the answer to his question is: because this bastard has something embarrassing to hide.

As a description of a one-off, this is fine. The problem is that this approach is the orthodoxy, and so Paxman is the standard-bearer – probably unwitting – for a variety of journalism that is as ineffective as it is grating. If you are not a Big Beast, there are reasons that this lying bastard might be lying to you besides a deep-seated dishonesty. He might be lying to you because you don't matter very much. He might be lying to you because the lie is easier, and the distance from the truth small enough to fudge. Or, most likely of all: he might not be lying to you at all. He might just be taking that tone, default for all politicians these days, because the bitter experience of interviews like this has taught him that it's best to keep his guard up.

Arguing about whether this is the fault of politicians or journalists is as pointful as that dispute about the chicken and the egg: the point is, it's the way things are. And so it is that the interviewers who really reveal something unexpected these days are a rather more artful, forensic bunch. Paxman's heirs, such as Evan Davis and Eddie Mair, are scrupulously polite; they draw out their subjects by degrees, and leave us to spot the omissions for ourselves. In such an interview, there may be only one difficult question – the crucial one. The rest of the discussion will be the construction of a house of cards so delicate that it takes only a puff of breath to knock it down.

None of this is to diminish Paxman. Indeed, it is a marker of his greatness that he is so inimitable. All the same, it's cheering to read that the front-runners to succeed him are the likes of Mair and Laura Kuenssberg. Their lips may not curl so high, nor their eyeballs roll so far. But imitation will get them nowhere in their quest to match the master.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments