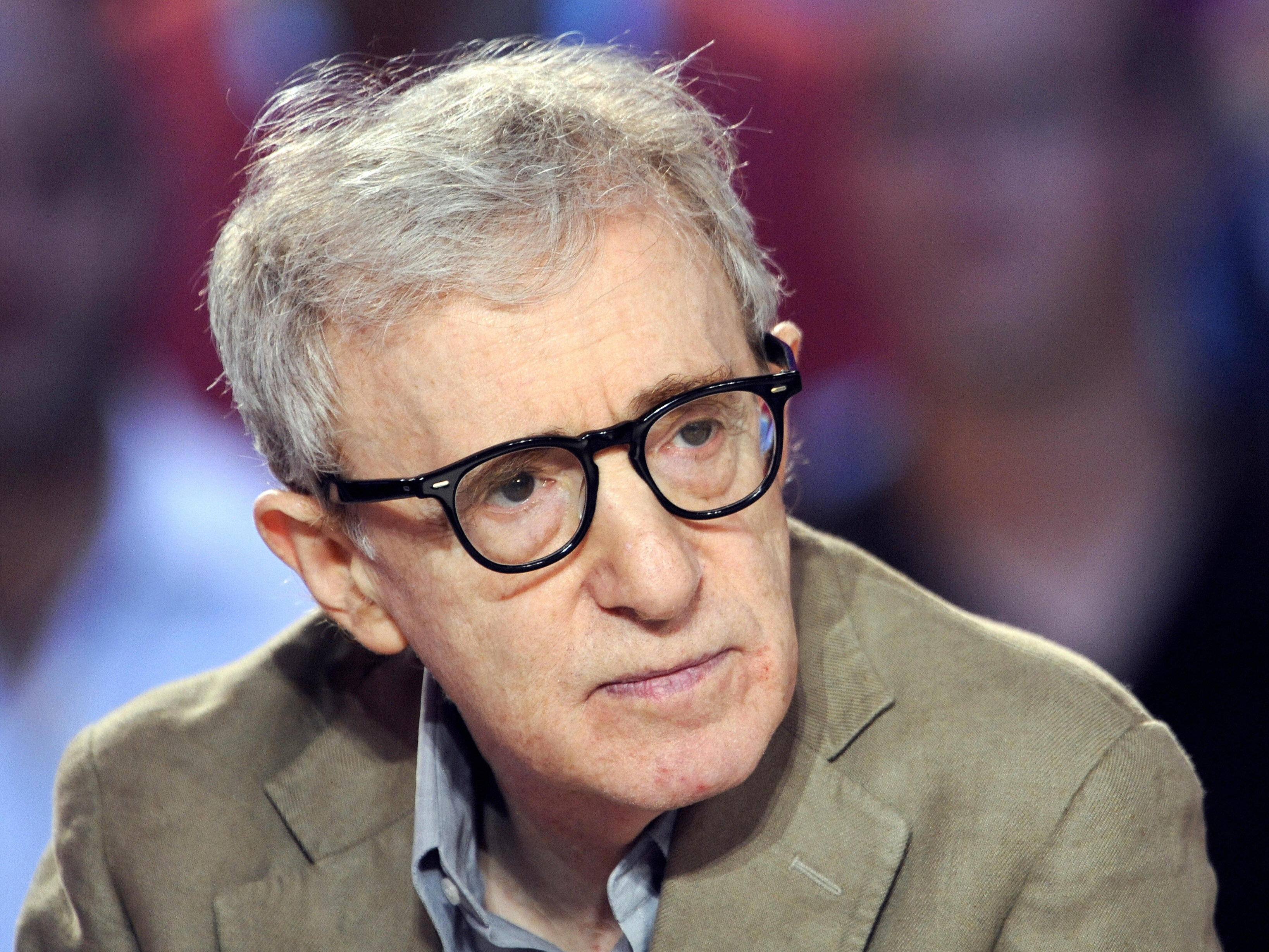

Woody Allen would like you to believe that he’s ‘oblivious’ – Allen v Farrow suggests a darker side

Yes, Allen v Farrow tells one side of the story, writes Rachel Brodsky. Perhaps that is intentional, as Dylan’s story has been twisted and disbelieved by Allen fans and members of the media alike

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Whichever side you choose to believe, watching Allen v Farrow is a draining experience. The four-part series, directed by Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick, rehashes and takes a much closer look at the decades-old childhood sexual abuse allegations Dylan Farrow made against her adopted father, celebrated filmmaker Woody Allen. Weaving together interviews with Dylan, family friends and babysitters, members of the Farrow clan, and even the case prosecutor, Allen v Farrow unearths long-buried case files and dissects the infamous Yale report, which purported to exonerate Allen of any wrongdoing.

In the wake of Allen v Farrow, all of this has been written about ad nauseum, with many observers, myself included, aghast at the revelations and footage of a seven-year-old Dylan telling her mother that Allen had touched her “privates”. Other writers have expressed understandable scepticism at the one-sided nature of Allen v Farrow, which did not include any interviews with Allen himself, nor his wife, Soon-Yi Previn, who the documentary heavily implies first became involved with Allen when she was still a teenager. Allen has always denied any truth to the allegations and reportedly did not respond to the filmmakers’ request for an interview. He has since called the series “a hatchet job riddled with falsehoods”, adding that the allegations are “categorically false”.

Yes, Allen v Farrow tells one side of the story. Perhaps that is intentional, as Dylan’s story has been twisted and disbelieved by Allen fans and members of the media alike, who would more readily believe that Allen is the victim of a scorned partner, aka Mia. One-sided though the documentary is, what truly disturbed me is the way Allen v Farrow portrayed a very different, icier version of the futzing, rambling, nebbish-like character Allen has played in his films. Meanwhile, in real life, he describes himself as “lazy” and uninterested in mainstream popularity. Read any number of interviews with Allen, and he portrays himself as someone who became a fabulously beloved filmmaker by pure happenstance. “If I sat down to do something popular, I don't think I could,” he told interviewer Stephen Farber in 1985.

And yet, a look at Allen through Ziering and Dick’s lens reveals a seemingly chillier, more vindictive person.

As the documentary points out, when Allen presents his relationships with much younger women in his films, he is the one who is chased by underage partners, not the one doing the chasing. In 1979’s Manhattan, Allen plays a 42-year-old TV writer who just happens to find himself dating a high-school student. When he pulls away, citing their age difference, Tracy (played by Mariel Hemingway) edges closer, confessing her love for him. It is Hemingway’s character that initiates and constantly asks for sex, not Allen’s. Allen v Farrow proposes that by framing the relationship this way, the director is in fact grooming his audience to feel more comfortable with a dynamic that would otherwise be frowned upon.

Iterations of this too-paranoid-for-sex persona peek out again, notably in Annie Hall, when Allen’s character Alvy is too wrapped up with a conspiracy theory about Lee Harvey Oswald to sleep with a young woman he meets, Allison Portchnik (played by Carol Kane). “I need your attention,” she says. “You’re using this conspiracy theory as an excuse to avoid sex with me.” It’s also worth noting that in this scene, where Allen’s character is waxing on about a conspiracy to kill Kennedy, he says, “You know the ethics those guys have. It’s a notch underneath child molester.” (Child molestation comes up quite a few times in Allen’s works. And remember when TV critic Emily Nussbaum pointed out yet another reference to molestation in a 2014 play of Allen’s, Honeymoon Motel?) The character of Allison is meant to be of suitable age, of course, but Allen’s neurotic, idiosyncratic caricature stays consistent throughout many of his films, and drowns out criticism around his alleged relationships with a series of young women (former model Babi Christina Engelhardt says she had an eight-year relationship with Allen that began when she was 16 and he was 41; his Manhattan co-star Mariel Hemingway says he invited her on a trip to Paris where they would not have separate rooms when she was 18. He’s responded to neither allegation).

Read more:

In a 2018 interview with Soon-Yi, she describes Allen as “a poor, pathetic thing” and “so naive and trusting”. Those words are difficult to square with the recordings of Allen speaking to Mia Farrow over the phone while investigators were looking into the allegations of sexual abuse.

“Is your phone taped?” Mia asks in one of many recorded conversations presented in Allen v Farrow.

“No, my phone’s not taped,” responds Allen. “I'm the last person in the world that knows how to, you know, work that stuff.”

A second later, Allen’s line beeps with a call waiting. Switching lines, he tells the caller: “Yes, can I call you back? I'm on the phone with Mia and I have been for the last 10 minutes. I'm not saying anything, but I’m just listening and taping.“

In another taped call, Mia begs Woody to take their situation out of the public eye (the director brought their case to the press after being accused in a blitz of press conferences and interviews). “You’re the one that’s speaking to Newsweek,” Woody accuses.

“I was told you were doing an interview with Newsweek,” Mia responds, sounding confused.

“I'm not doing an interview with Newsweek, no.”

Soon after, an August 1992 issue of Newsweek surfaces blasting the headline “Woody’s Story: He and his new love [Soon-Yi] speak out about their romance – and Mia’s explosive charges.”

It bears repeating: Allen, by his own description, is a “lazy” filmmaker. His films cost little to make and he, again by his own admission, would rather just be done every day at six o’clock to go and have dinner than stick around and analyse every shot. Although Allen purports to be “lazy” and has been observed to be “oblivious”, he went to impressive lengths in the 1990s to take Mia to court and strip her of her children. It seems ironic that, according to Vanity Fair writer Maureen Orth, “he hauled Mia into court for everything from visitation rights to firing the children’s therapist” and reportedly hired a legal team specialising in intimidation tactics, such as “[hiring] a phalanx of private investigators to shadow Mia’s children and the state police investigating the case”.

Of course, even “lazy” and “oblivious” people with money and resources may do just about anything to defend themselves. Even “lazy” and “oblivious” people might be advised to work with a “very imperious, very rigid” publicist. The 2018 story on Soon-Yi was done by a writer who proclaimed to have been a longtime friend of the director’s. Another writer for The Guardian spoke to Allen last year, and has written a lengthy defense of him upon Allen v Farrow’s release, calling the film “pure PR”. (Also, just because a story is one-sided, that doesn’t make it PR. PR involves crafting a narrative for personal gain, and I can’t imagine Dylan or anyone involved in Allen v Farrow has anything to gain by revisiting this alleged trauma except perhaps closure.)

Any entertainment journalist knows that extraordinarily famous subjects, if they still have control of the narrative, will have the privilege of cherry picking from the “right” publications and the “right” journalists to help move their story along the “right” track. Allen’s long-revered comic genius might be very real, but something that Allen v Farrow suggests, that I completely believe, is that his brilliance extends beyond the filmmaking sphere and into far darker, more disturbing territory.