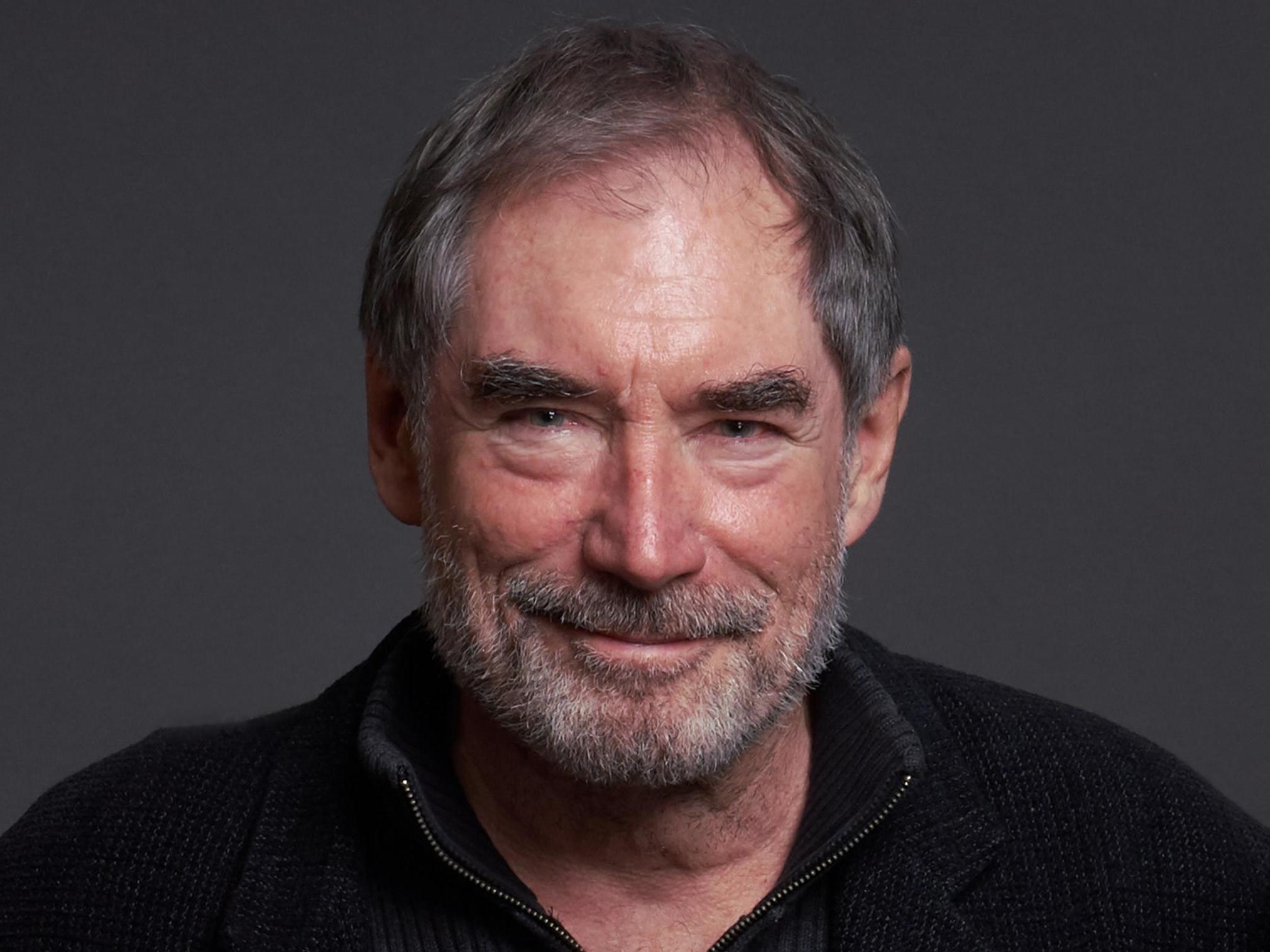

Timothy Dalton: ‘Why do we need to offer people gratuitous sex in film? There’s plenty of porn online’

The former 007 is still going strong on television, most recently in superhero series ‘Doom Patrol’. Now 74, he talks to Helen Brown about his secret past, steamy scenes and why we need to preserve our innocence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Timothy Dalton has a laugh like a pantomime villain. Rich, deep and playfully thespy, it booms from our Zoom chat as his press team asks me to pivot my camera away from a nice blank wall towards a pile of unwashed laundry, to improve the lighting. The laughter erupts again when he spots my broken hoover.

I’m rewarded with a third, expansive peal when I tell the 74-year-old actor that my 10-year-old son – eavesdropping from the hall earlier as I watched the delectably surreal but 18-rated series Doom Patrol – said of Dalton’s performance as Niles “Chief” Caulder: “His voice is a massive spoiler! I mean, the posh English guy in an American action thing? You just know he’s going to turn out to be a baddie! Even if he’s a good guy for now.”

“Good for your son!” Dalton chuckles. “After I shot my very first scene for the show, a crew member said, ‘I wouldn’t trust you an inch!’ But it’s essential to play the bad guy as a joy to watch. You have to give him a twinkle. ‘He’s behind you!’”

Best known for playing a brooding, burnt-out James Bond during the franchise’s commercial decline in the 1980s, Dalton has sprinkled a compelling twinkle over every role, from his film debut as Philip II of France in The Lion in Winter (1968) to his voicing of Mr Pricklepants in Toy Story 3 and his compelling turn as the manipulative Sir Malcolm in Showtime series Penny Dreadful (2014-2016).

Aimed at fans of films like Deadpool, Doom Patrol is one of the most stylish and witty comic book series on TV at the moment. While it comes slathered in layers of pantomime – including a snarky, fourth wall-busting narrator sneering “more superheroes on TV, just what the world needs” – the show’s real power lies in the emotional credibility and complexity of its characters. It constantly teases viewers with the absurd idea of goodies and baddies, while giving each character a turn flexing the powers of good and evil within themselves.

The show is based on the cult comic books created by Arnold Drake and Bob Haney for DC Comics in 1963 and made trippier by Grant Morrison in the 1980s. It’s about a motley crew of superpowered misfits, including a glamorous 1950s movie star who dissolves into a terrifying blob when distressed (April Bowlby), a gay test pilot possessed by a deadly electric ghost (Matt Bomer), a cyborg (Joivan Wade), a brain in a robot (voiced by Brendan Fraser), and a rebel chick with 64 different personalities, each of which comes with its own superpower (Diane Guerrero). Fans of more vanilla superhero fare should be aware this show comes with magical farting goats, SeX-Men (a joke about Drake’s argument that the X-Men were a rip off of the Doom Patrol), floating buttock balloons and some very creative compound insults (in one episode, a character accurately dismisses another as an OCDalphadouchewaffle).

Operating as a dysfunctional family, these traumatised characters live together in a dilapidated mansion under the quasi-parental care of Dalton’s wheelchair-using scientist, Niles Caulder. A murky character, Caulder rolls in and out of low-lit flashbacks throughout season one, as he’s been kidnapped by a “Mr Nobody” (do clock the Homer’s Odyssey reference) and the team are on a quest to rescue him. He gets much more screen time in season two, which Dalton describes as “emotionally richer, stranger and more profoundly human” than the first series.

When it comes to discussing his own complex humanity, Dalton is a cagier – if unfailingly courteous – interviewee. When a conversation about his own interest in comics (he hasn’t read any since flipping through The Dandy and Beano, aged seven) leads me to ask what kind of a child he was, he splutters: “I don’t examine what kind of child I was!” Then he briskly assures me: “I was a normal child! I was into sports, I was quite intelligent, I grew up to be an actor.”

Although actors are not always normal, they are, he tells me, less likely to experience the same weird lockdown dreams as the rest of us. Because they live in a fantasy world, they dream more of reality. “Even if you’ve rented a nice house or a nice hotel while you work,” he says, “it’s not yours. The pictures aren’t yours. Your books are not around you. You go to work in the dark. Your colleagues are all wearing somebody else’s clothes, pretending to be somebody else and so are you. Then it all ends 18 hours later and you come home in the dark and get something to eat. Then you start having dreams about your history and you go a bit bonkers, a bit potty, a bit crazy.”

Details about Dalton’s past are sketchy. I look online and the internet tells me Dalton was born in Wales and raised in Derbyshire. His mother was (perhaps) American and his father (possibly) was in the Special Operations Executive during the Second World War before moving into advertising. Young Dalton went to Rada aged 16 and quickly got his stage start with the Birmingham Rep, where Brit greats Paul Scofield, Derek Jacobi and Albert Finney also got their starts.

But this may not all be true. Dalton tells me that, after a brief period of being “niggled” by the “totally ridiculous, utter drivel” that passes for his biography on Wikipedia, he has been able to see “this wall of lies protects me, in a way. Although it is also disrespectful of a life. The place where I lived was wrong, the fact I’d been in the air force was wrong. Although it is true that I learned to fly, back when I was at school,” he softens. “I mean, you have to remember that I was at school during the Cold War. We had to dress up in khakis and heavy boots half an hour a week and pretend we were soldiers.”

When he was 17, there was a competition in which you could win a guaranteed role as an officer in the RAF and be taught how to fly. “I had no interest in being an officer,” says Dalton, “but I did want to fly.” He won it and was sent to an airfield in Skegness. “I was taught to fly by an ex Battle of Britain Spitfire pilot. It was the most wonderful experience, being free in three dimensions. Such joy and excitement… I’m not sure how much of that I took into my career but it taught me to take leaps into new worlds, new areas of yourself, which is what acting’s about. But I think I’ve always had that in me. I’ve always looked for a challenge, for something new.”

Dalton says his craving for ever-changing horizons has been met by modern TV, which has seen him relish a leading role in Penny Dreadful as well as Doom Patrol. “In film and theatre, you always know where you’re going. You know the ending. In TV, the writers are always changing their minds as it goes on. You work, you discover, you work… step by step. You go down blind alleys, you have awful moments waking at 3am. But it’s an exhilarating journey as things come together. With Caulder, if I had known he would start being really bad in a few hours’ time, then I could have started being really nice at the beginning. You could lead people… you know?”

Before our call, I have been warned not to ask about Dalton’s personal life (including marriages to English actor Vanessa Redgrave from 1971 to 1986 and Russian singer-songwriter Oksana Grigorieva from 1995 to 2003) or his role as James Bond in The Living Daylights (1987) and Licence to Kill (1989). I’ve no wish to pry into his love life. But it’s frustrating to be barred from discussing his Bond. Though unfairly dismissed at the time – one critic felt that he lacked “the manliness or the charm” of his predecessors; Roger Ebert said Dalton had failed to understand that Bond was supposed to be “preposterous” – his performance has recently been reappraised. It’s even harder to resist bringing up 007 when he tells me he’s been reading Graham Greene’s 1978 spy thriller, The Human Factor, during a “nightmare” lockdown.

I’m among the fans who admired Dalton’s portrayal of the spy as a dark, damaged character. I’ve never liked the “Carry On Spying” of Roger Moore and Sean Connery. All that winking and sex and death. I preferred Dalton’s decision to go back to Fleming’s books and see Bond as a pretty difficult character, not a national treasure, one who killed for money and treated women like pretty, disposable gadgets.

Dalton has form with wounded heroes. I first saw him on screen as the (true to text) witty and brooding and (untrue to text) handsome Mr Rochester in the 1983 BBC miniseries of Jane Eyre. My mum called him “dishy” and swooned as she told me she had done when he played Heathcliff in Robert Fuest’s Wuthering Heights (1970). It’s a character type he also sent up to wicked effect in Hot Fuzz.

The unquiet ghosts – dark but relatable – of both roles blow through his portrayal of Niles Caulder. “On one level,” he says, “you could call him an absolutely ruthless, self-serving individual. But then, whatever he’s done, he does love these people. I mean, on another level, he loves them because he made them. And you have to remember that he might also say terrible things to deflect the bad guys. He loves his terribly, terribly dangerous daughter. He loves her enough to give up what you see he gives up in the second series.”

This is definitely the moment to flag Doom Patrol’s marvellous female characters. My favourite part from season one was a pure #MeToo revenge fantasy. It featured the Hollywood star Rita going to ask a studio executive for a role, only for him to pat his knee and ask how hungry she was for the part. Stressed, she inevitably turned into a blob and suffocated him. When the man’s secretary hears a disturbance and walks in, she doesn’t scream. Like a cooly supportive member of her gender, the secretary takes in the scene, tells Rita her boss has clearly had a heart attack and “you were never here”.

“Yes, that shift is very interesting,” says Dalton, who says this attitude extended off screen, too. “When I was with Pisay Pao, who plays Niles’s daughter’s mother, we had meetings and legal contracts about what we should and shouldn’t do, what we didn’t want to do physically. I got really pissed off with it all.” He felt initially that it didn’t need contracts, “because I was determined to make sure she was OK and I was OK. And actually I was wrong to be irritated. Because it was in our favour. Anything we said we didn’t want to do – about sex and love and bodies – wasn’t done. It’s better these days.”

Through his career, he must have seen women being treated poorly? “I know the girls don’t like it, when they’re asked to take their clothes off or do nude shots. They do it, but they don’t like it. They’re always upset. Well…” he pauses. “That’s a generalisation. But many times, I have seen women upset. I will also say I didn’t like it either. Most of the time it’s not necessary. There’s plenty of porn online. I think if people want to see naked bodies they can go online and find it. Those of us trying to make good, serious work… why do we need to offer people gratuitous sex? It’s not necessary. It’s silly to put people in situations where they are embarrassed or where they’re worried about what their kids or husbands are going to think about them. The work is not meant to make actors unhappy. It’s meant to be good for the audience and good for us.”

Other actors on the show have praised Dalton’s professionalism and commitment. Bowlby has said he regularly works longer hours to ensure the shots are right. I ask Dalton what drives him to work until 3am and book his own Uber cabs long after his colleagues are soaking up their beauty sleep. “We have to preserve the child in ourselves!” he says. “We have to preserve the innocence and work well. I always have anxieties. I always worry about getting it right.” But can’t he relax now? Doom Patrol has a 96 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes. He’s had great reviews!

“Have I? Had good reviews?!” Dalton looks genuinely surprised. I tell him he’s reaching a whole new generation with Doom Patrol and over 12,000 people have liked the YouTube video of his best scene (the spectral waltz) in Penny Dreadful. “Wow! I’m sitting in my little office in LA and I hear that and… well. Wow.”

With Doom Patrol, Dalton says, “acting becomes a playground of the imagination. You can go as far as the mind chooses to go. There is such freedom…” So if Dalton could pick a superpower, what would he choose? He looks bored and says: “Insight!” But, amusingly, the former 007 brightens up as he gazes back over my shoulder. “Really,” he twinkles, “I’m thinking I should throw some clothes into the machine or help fix that hoover... I mean, I can always do a bit of hoovering!”

Doom Patrol season two is available to stream on Starzplay

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments