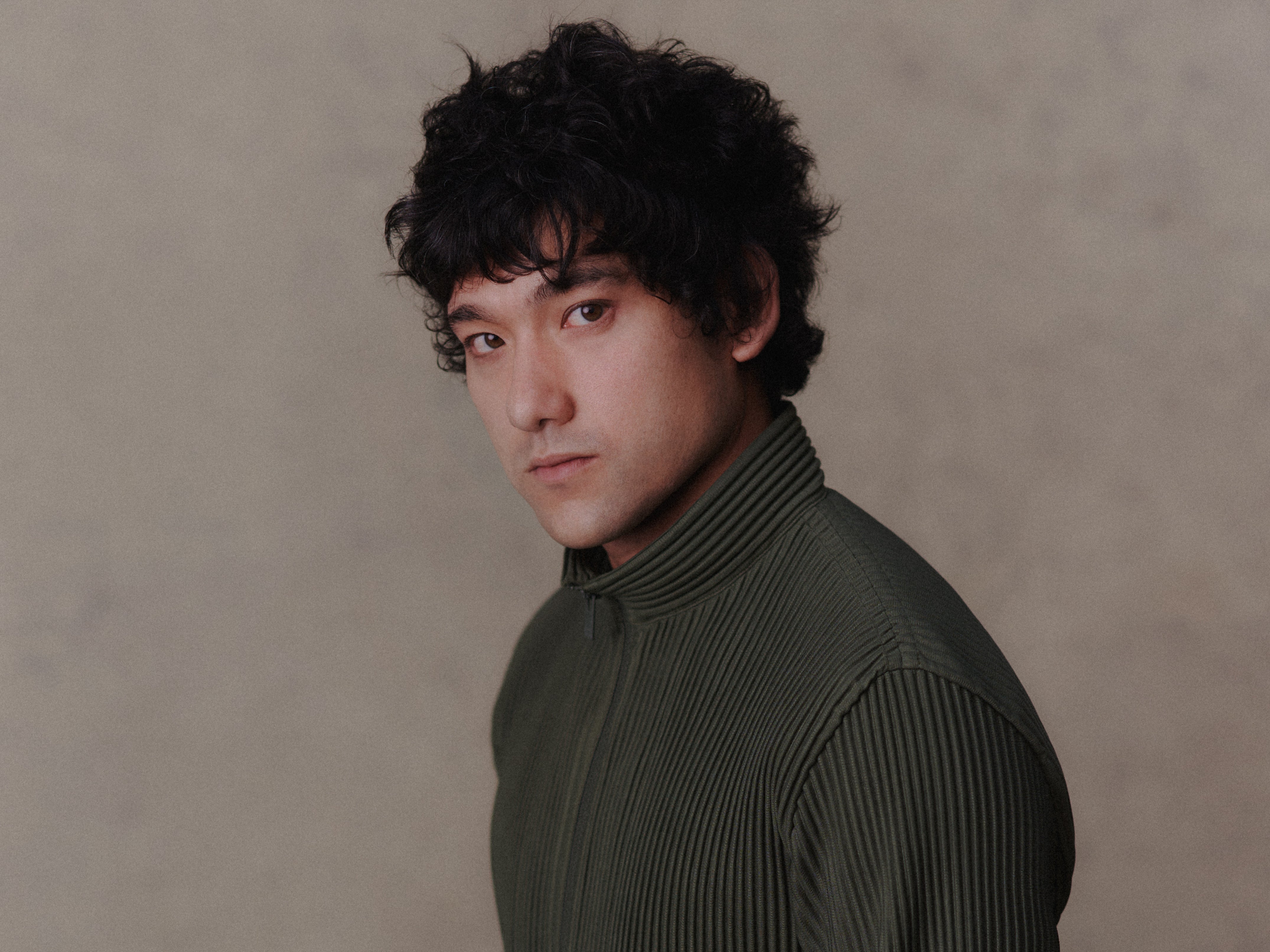

The White Lotus star Will Sharpe interview: ‘One time Jennifer Coolidge wore a Russian hat at dinner’

The actor-writer-director spilt his heart onto the screen for his 2016 masterpiece ‘Flowers’. Now he’s practising his restraint in season two of ‘The White Lotus’. He tells Ellie Harrison about getting under the skin of his characters and working with national treasures Jennifer Coolidge and Olivia Colman

Will Sharpe is the secret ingredient. The actor-writer-director is to television what a spoonful of instant coffee is to a tasty bolognese. With his eccentric masterpiece Flowers, the “sitcom with a mental illness” that ran on Channel 4 from 2016 to 2018, he quietly wrote Oscar winner Olivia Colman one of her most brilliant – if least known – parts. In 2019, his witty, razor-tongued performance as a self-sabotaging rent boy in BBC Two’s London-Tokyo thriller Giri/Haji had fans calling for him to get his own spin-off, and won him a Bafta.

Sharpe’s writing and directing on 2021’s Landscapers – a show about a real-life killer couple, which aired on Sky Atlantic – elevated the miniseries from what, in the wrong hands, might have been sensationalist true crime, to romantic psychodrama. And in his latest project, season two of the delicious black comedy The White Lotus, Sharpe is the unsettlingly still centrepiece of a friends’ holiday from hell. Sharpe isn’t the face of any of these shows – he’s tinkering behind the scenes in some, acting as part of an ensemble in others – but without him, they might have lacked that unique zing that turns a good recipe into a great one.

The White Lotus’s first season was TV’s breakout smash of last year, winning 10 Emmys for its merciless mockery of the one per cent. Set in the fictional White Lotus luxury resort in Hawaii, it placed us in the (very deep) pockets of a group of self-obsessed, rich Americans, and earned itself a reputation as the best satire of our times. For its second season, a new set of guests have jetted off to Sicily’s White Lotus, in the tourist town of Taormina, where the lava-spewing Mount Etna looms large over the sprawling hotel. “It’s interesting how the location affects the series,” says Sharpe. “This season feels darker... as if it has this operatic quality to it, like a Roman tragedy or something. The volcano being right there was sort of surreal” – he lets out a nervous laugh – “and it does affect the psychology of the show.”

Sharpe plays a newly minted tech entrepreneur called Ethan, who – along with his lawyer wife Harper (a sublimely uptight Aubrey Plaza) – has been invited to Sicily by his old college roommate Cameron (Theo James) and Cameron’s wife Daphne (Meghann Fahy). As Sharpe says, “It’s almost like they’ve come on holiday together by mistake.” The two couples are chalk and cheese: Ethan and Harper are conscientious, news-reading, intellectualising cynics, while Cameron and Daphne are indulgent, PDA-loving optimists. It’s not going to end well.

When I speak to Sharpe over video call, he’s staying in rented accommodation while his partner Sophia Di Martino – an actor, too, and one of the stars of Flowers – is working. The 36-year-old is wearing a turquoise top with a shirt over it; his black rocker hair is swept to the left. He’s in a room with dark navy walls and high, corniced ceilings, which he casts his eyes up to whenever he’s searching for the right phrase. I can hear the couple’s children squealing with delight somewhere in the house.

Sharpe is a little shy, and softly spoken – traits he accentuates to potent effect in The White Lotus. Poor old Ethan takes a lot of crap. Harper is so neurotic and domineering that Ethan practically has to ask her permission to order the fish at dinner (“I just don’t like it when it’s too fishy,” she groans). Cameron, meanwhile, “alpha-dogs” him – mocking him for his poor motoring skills and for being “the original incel” in college. Through all of this, Ethan just smiles sweetly, blinks slightly. At some point – it’s inevitable – he’s going to snap.

“He’s getting it from all sides,” says Sharpe, who seems to be equally cerebral. “As I was trying to get into Ethan’s head, I started trying to do the run that he does up a very steep hill every morning in Taormina. The first time I did it, I thought I was gonna die, and then it gradually got easier. But there is something inevitably existential about being high up in a beautiful place, and I can see how that could add fuel to a fire, or leave space for him to start simmering away. There’s definitely something going on internally with him – some looming crisis.”

Not only are Ethan and Harper suspicious that they’ve been invited away by Cameron and Daphne to be paraded around as their liberal, diverse, “white-passing” friends with Japanese and Puerto Rican heritage; they’re also confronting the fact that their own marriage has gone a bit stale. “There’s this unhelpful lack of mystery,” says Sharpe, “to the extent that when Harper walks in on Ethan masturbating, he doesn’t even pretend that he was doing something else.” Has Sharpe met people like Ethan and Harper? “I’m sure I have,” he says, “but people aren’t habitually open about those intimate, gnarly details of how the relationship actually is.”

In the background of all this is the unhinged millionaire Tanya, played by Jennifer Coolidge – the only actor from the show’s first season to reprise her role. Sharpe didn’t shoot many scenes with Coolidge, but he did enjoy the “strange chaos” the American national treasure brought to everything she did. “It’s really infectious,” he giggles. “There was one time when she wore a Russian hat at dinner.”

Sharpe has made some of his best work with another national treasure: Britain’s own Olivia Colman. He cast her in Flowers because he knew he needed to fill the show with “actors who had funny bones” but could also do depth and melancholy. He thinks Colman – who played the flirtatious, misguided Mrs Flowers – is “ace” and “exhilarating” to work with. Colman clearly thinks the same of him, as she selected him to work on Landscapers, written by her husband Ed Sinclair – just like Benedict Cumberbatch singled him out to direct the whimsical biopic The Electrical Life of Louis Wain.

When I’m in a certain state of bipolar, the colours seem especially vivid

But Flowers is the show that changed his life. Made five years after his debut feature film, the charming little curio Black Pond, Flowers was his first proper “grown-up commission”, as he puts it. The show gave him the confidence to call himself someone who makes TV and films for a living.

Sharpe, who is half Japanese and lived in Tokyo until he was eight – he was born in London and, after Tokyo, grew up in Surrey – describes it as “a family sitcom, but one where you ask the characters how they’re really feeling, what’s really going on with them, and they don’t have to be trapped at surface level”. The first season introduced us to Colman and Julian Barratt as Deborah and Maurice Flowers, who live in a tumbledown house with their dysfunctional twins Amy (Di Martino) and Donald (Daniel Rigby). Sharpe played an illustrator who works with Maurice, called Shun. Flowers season one was full of poetic gloominess, but its second and final year was comparatively an explosion of colour and light, and followed Amy’s struggles with bipolar disorder and hypomania.

Sharpe himself has type two bipolar. Writing his experiences into a character played by his partner was “emotional”, he says, but they “have a good way of separating work from life”. He used vivid colour in that season to get across what it can feel like to experience hypomania – periods of overactive, excited behaviour that someone with bipolar might experience.

“Coming up – or when you’re high, as it were – it can feel good,” he says. “And the dangerous thing about it is that if you’ve not been feeling so good, it can almost feel like you’re starting to get better. It can feel like you’re actually sort of feeling OK now. And then you can get carried away with it. I do find that my senses change, and for me, when I’m in a certain state, the colours do seem especially vivid. So I wanted the second season of Flowers to feel very sensory.”

When I ask whether he ever felt he had made himself too exposed, too vulnerable, by sharing Flowers with the world, he murmurs a quiet “Wow”. He seems to struggle with the question. He looks up at those cornices. Laughs a little. “I felt compelled to do it, I suppose.”

Di Martino wasn’t the only loved one of Sharpe’s who collaborated with him on Flowers. The score for the show, along with those for Landscapers and Louis Wain, was composed by his brother, Arthur. “When he sent me the first demo for Flowers,” says Sharpe, “it really helped me to get a sense of the world a little bit. It was a slightly dark but also mischievous track that had this slightly cheeky, lilty feeling to it. I found that genuinely quite influential in the early stages.

“[Arthur and I] are close and work closely together, but we don’t have the sort of relationship where we go for a drink and talk for hours and hours about life. But because we work together on stories that are emotional and are about life, I have a sense... that’s almost how we communicate a little bit. He knows what’s going on with me from scripts, and I can feel what’s going on with him through the music he’s writing.”

This story about how he connects with his brother doesn’t surprise me – Sharpe has a tendency to be quite ambiguous, tentative even, and he takes a fair bit of coaxing. It certainly seems that the best way to read him is through what he puts on screen.

Given that Flowers is his most intimate work, that’s a good place to start. But he’s got no plans to make more of it. “Probably not. Never say never,” says Sharpe, who has said before that he’ll think of his life as pre- and post- that show. “It turned out to be a very personal project, and I was unpacking stuff about myself that I didn’t realise I needed to unpack, saying things I didn’t realise I needed to say. I found it, all round, a very beautiful experience.”

As we’re about to wrap up, Sharpe goes back to the answer he was stumbling over earlier, about laying bare his soul in Flowers. “As to your previous question,” he says, “it was the vulnerability, and the readiness of everybody involved to come with me on that journey, that...” he searches for the words again – “that made it special.”

‘The White Lotus’ is exclusively available from 31 October on Sky Atlantic and streaming service Now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks