Star Trek 50th anniversary: A celebration of the original TV series and its unique vision of the future

Although it only lasted for three series, the science fiction show's first incarnation is still inspiring film-makers and fans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 8 September 1966, a new weekly drama series made its first appearance on American network television. “Space: the final frontier,” the voice-over intoned, as a curiously shaped vessel whooshed past. “These are the voyages of the Starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilisations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.” And the theme tune, even then sounding a little creaky and old-fashioned, roared in.

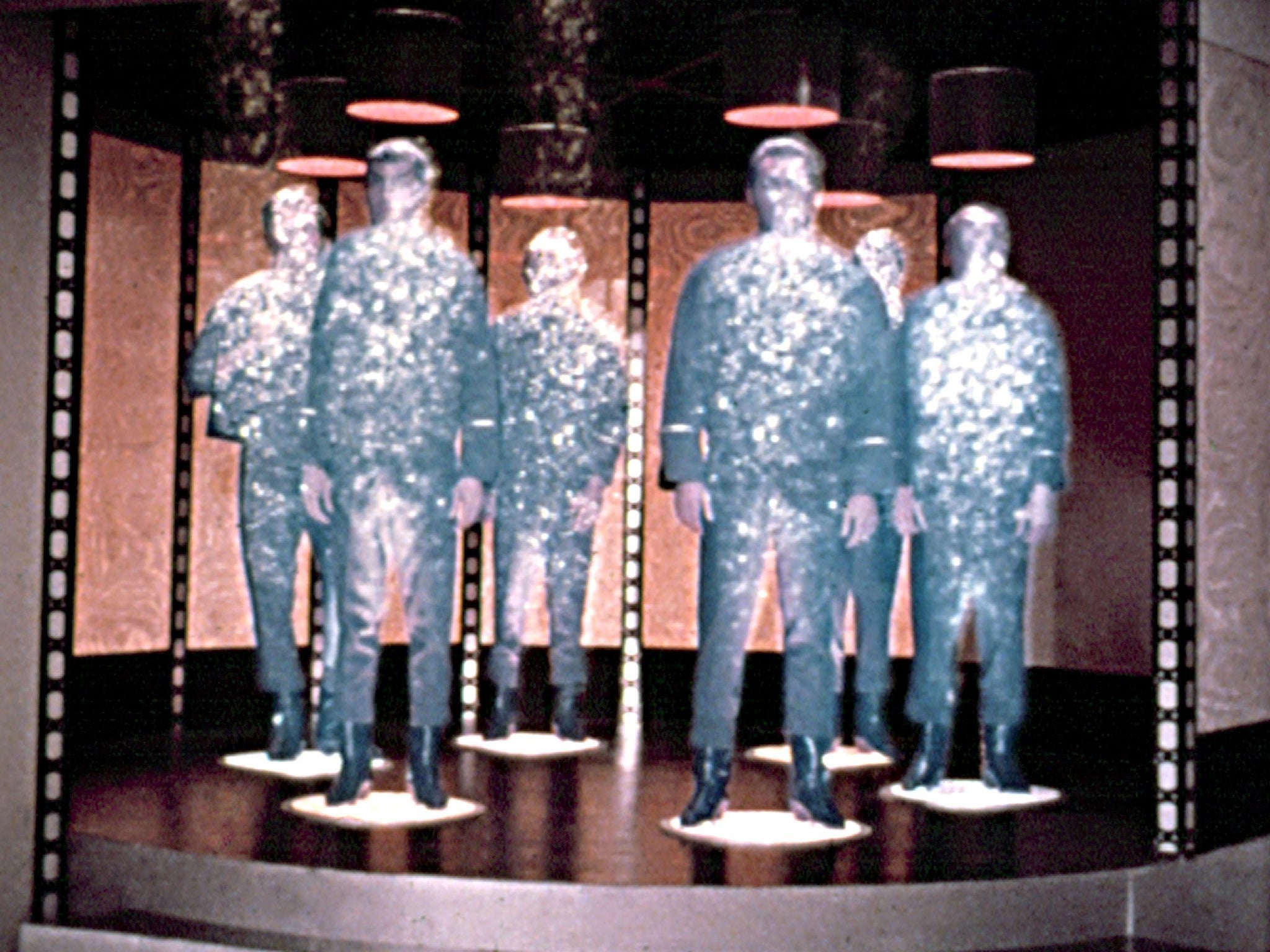

Its first viewers, if they didn’t flip channels to watch something else, will have discovered a world, or maybe universe, that had already been imagined in some detail. Transporters, shuttlecraft, phasers on stun, warp engines, dilithium crystals: they are all there, right from the beginning. In other, equally important ways, though, the Star Trek universe resembles our own. The captain is a young man, good-looking, charismatic, clever, a strong leader. His second-in-command, the man with the ears, is even cleverer. The ship’s doctor is a crusty old everyman, a sawbones. The engineer is Scottish. All the women wear terrifyingly short skirts. It’s the 1960s, 300 years on.

That first episode, “The Man Trap”, wasn’t the best or most distinctive episode with which to start. It was the 10th to have been made, but it had a monster in it, and NBC wanted to start with a monster. Other science-fiction shows had monsters. Viewers liked monsters. Network executives liked monsters. Everyone knew where they were with them.

Science-fiction television was not an advanced form in 1966. Lost in Space, considered a kids’ show in the UK (because essentially it was), was as SF as you could get on US prime time. “Danger, Will Robinson!” said the Robot. “The pain! The pain!” said Dr Zachary Smith. And having landed on a new planet, which looked exactly like the previous week’s planet, the extraordinarily dull Robinson family would immediately be threatened by the latest monster – or as we thought of him, the man in the monster suit.

(Irwin Allen, the creator of this show, had a profitable line in SF concepts that never progressed, ever, by a single nanometre. Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea found what at the bottom of the sea? Monsters, usually. In Land of the Giants, an Earth spaceship landed on a mysterious planet where everybody they encountered was 12 times larger than they were, but still spoke English in an American accent. The crew spent two years and 51 episodes avoiding giant beetles.)

Star Trek was designed to be better than this. With its sucker-thumbed, shape-changing salt vampire, “The Man Trap” was atypical, and you get the feeling that NBC never forgave or forgot. The three-year history of the series would be one of constant battles with an unsympathetic network, which never began to work out what it had within its grasp. NBC drifted out of the picture in 1969, when it cancelled the show, but Star Trek is still with us, 50 years later. To be celebrating its half-century, possibly with a glass of Romulan ale, seems bizarre. Television shows come and go, and the vast majority of them stay gone. But Star Trek has come and gone and come and gone, and it’s here once again in the form of JJ Abrams’s rebooted film series. One day, I’m sure, it really will all be over, but we may all be dead by then.

I came to Star Trek both early and late. I saw the first episode to be shown on British television and was instantly entranced. This was in the summer of 1969, and I was nine years old – so I wasn’t to know that, although I was an early adopter in the UK, the series had already run its course in the US and been cancelled. A new generation of British fans was being nurtured as their American equivalents were writing furious letters to the network and tuning tearfully into the syndicated re-runs on local television stations. But the effect, if delayed, was much the same. At my school it rapidly became clear that you were either a Star Trek fan or a Doctor Who fan – a Trekkie or a Whovian, as we might now say in moments of weakness. I was always a Trekkie. I watched Doctor Who with pleasure, and I still do, but such loyalties are imprinted young, and they neither fade nor falter.

A quick word on terms here. The word “Trekkie” has long carried a slight tone of flippancy or even disparagement, possibly from the days when to be a signed-up fan of anything was to cash in all your remaining dignity chips and settle for a life of chronic uncoolness. To be a Trekkie was to contemplate buying Star Trek uniforms and wearing them in the privacy of your own home. I never went that far, although I did buy James Blish’s novelisations and read and reread them while waiting for the episodes to be shown again. When I played Star Trek games with my friends, I always wanted to be Captain Kirk and was very disappointed if I ended up being Mr Sulu.

Some time in the 1970s, though, Trekkies became tired of people laughing at them and decided that thenceforth, they wished to be known as Trekkers. I always thought this was a bad move. The implication was that Trekkies were sad and lonely individuals with no lives, while Trekkers were more outgoing, culturally inclusive types with good jobs and attractive partners, but I’m not sure anyone was fooled. Indeed, it seemed to me that saying “I’m a Trekker, I’m not a Trekkie” was far more tragic and desperate than actually being a Trekker or a Trekkie. Who cares what anyone else thinks? It’s a great series and I have never seen any problem in acknowledging my love of it. To come out of the Trekkie closet, you need to have been in it in the first place.

That said, the book I’ve written isn’t really aimed at the deranged Trek fan, whether Trekkie, Trekker or some other subgroup I haven’t identified. There are already hundreds of books geared towards the specialist market, from detailed histories and photographic records, to fascinating monographs on the science or design of the show, to autobiographies of the participants and, in the greatest profusion of all, spin-off novels, of which there are so many you wouldn’t know where to start. What I haven’t seen is a book aimed at the general reader, at the person who has grown up with Star Trek and watched it with enthusiasm, but has never felt the pressing need to wear a prosthetic Klingon forehead over their real head. That’s the book I’ve tried to write.

So why Star Trek, exactly? It’s a question often asked by those who don’t get the show, and answered, sometimes with difficulty, by those who do. Failure, in a television show or anything, is often too easy to diagnose and deconstruct. Success can be slightly more elusive. But taking it from the start, I think there are three significant factors.

The first was the show’s palpable seriousness. Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s mercurial creator, pitched his series to NBC as “Wagon Train to the stars”, which promised simple, solid action-adventure with an outer-space setting. But he had a higher intent. Star Trek was conceived from the beginning as a vehicle for serious dramatic themes, artfully concealed behind standard action-adventure conventions. Roddenberry’s first pilot for the show, “The Cage”, was thoughtful, talky...and a little slow. NBC said no and asked for a bit more fighting. Roddenberry learnt quickly to moderate his preachy tendencies and throw in a few space battles, but the show’s underlying seriousness was never diluted. When he unveiled the second pilot at an SF convention in early September 1966, an audience of 3,000 SF aficionados (including Isaac Asimov) applauded wildly, and asked to see more.

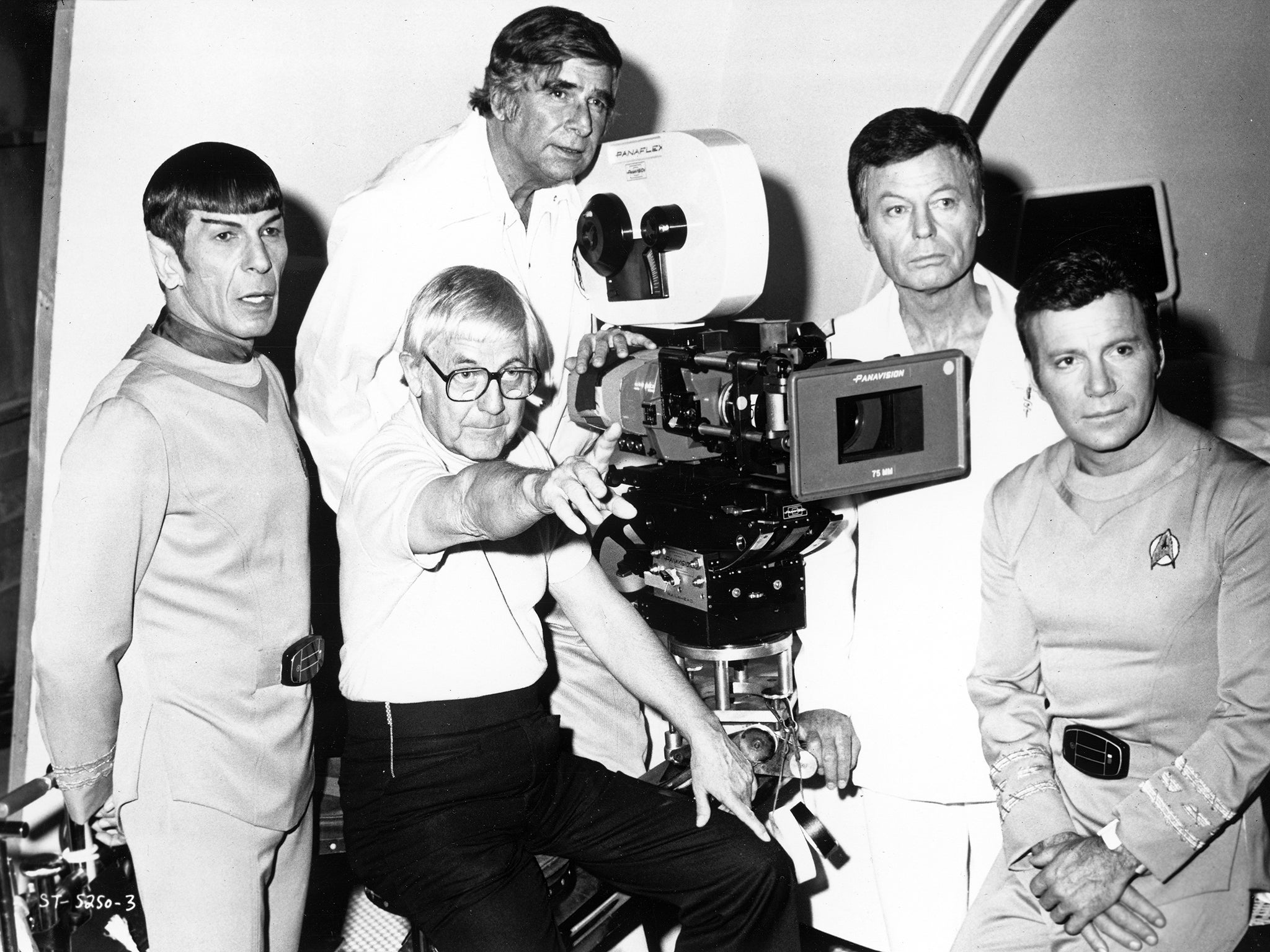

The second factor was the characters. The grand trinity of Kirk, Spock and McCoy took a pilot or two to come together, but once they did, their chemistry was so strong you felt they had been doing this for years. The first series of Star Trek finds its feet astonishingly quickly – you might say miraculously so. From nothing to “The City on the Edge of Forever” in less than a year is some going. It was the strength of the characters, and the absolute suitability of the actors who played them, that made this possible.

Finally, and crucially, the show’s optimism. Science fiction is a miserable old genre. Almost all of it is telling us how appalling the future is going to be. Its raw material is how appalling the present is; it then stretches and twists it and extrapolates from it, and the result can usually bring the most cheerful soul to the edge of breakdown. The great science-fiction films of the 1950s were almost all warnings of incipient catastrophe. The only previous American SF television series of note, The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, were not so much pessimistic as nihilistic, if often playfully so. Star Trek, by contrast, really did boldly go where no man had gone before. It posited a future where, broadly, things worked. Our world had found peace, money had been abolished, poverty had disappeared, humanity had finally become civilised. Now we were venturing into deep space on a mission of peace and exploration, not to conquer but out of sheer curiosity. And every problem we encountered, we felt we had a chance of solving, mostly in less than 50 minutes of screen time. My God, even religion had been abandoned.

The late 1960s were turbulent times, and Star Trek’s optimism, if they noticed it at all, might well have suited the NBC executives’ innate conservatism and cautiousness. Anything with a more obvious counter-cultural message would not have crept under their radar. Instead, Star Trek carried all sorts of unobvious counter-cultural messages, which its audience delighted in. Its bridge crew included a black woman in a position of responsibility. In the second series a young Russian ensign with a slightly unexpected Beatles haircut was introduced. In the future, we understood, clever and well-intentioned people would prevail. Those of us growing up who happened to consider ourselves clever and well-intentioned found this very much to our taste.

And what I think has enabled Star Trek to keep going is that there has never been anything else quite like it. One or two other shows have briefly taken up the baton, but remarkably few have been directly inspired by this most apparently fertile of formats. Maybe Roddenberry’s vision was so particular that other producers did not even try to duplicate it. Later Star Trek producers knew not to mess too much with it. Like a Borg cube, it appears to be resistant to attack.

What I’m doing is celebrating a very singular television show, for all its many and varied incarnations. That’s not to say that what I’ve written is moist-eyed with uncritical adoration, for that which we love can also drive us mad with rage and disappointment. As one episode title asks, “Is there in truth no beauty?” (“For the world is hollow and I have touched the sky”, says another.) This was at a point in the series when the episode titles were more enjoyable than anything you might see in the actual show.

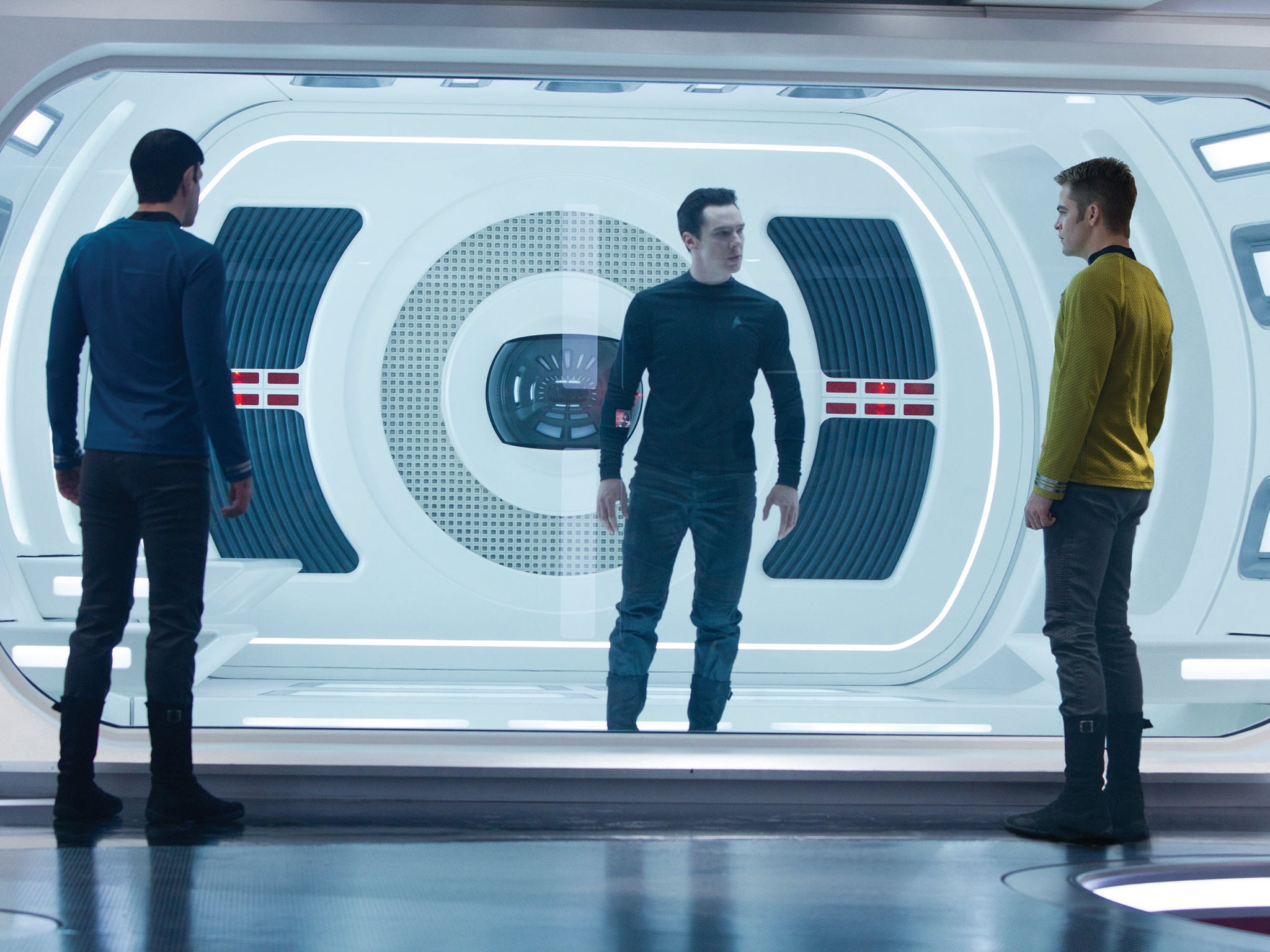

Story, of course, is everything. Star Trek had some of the best stories you could see on television, but its own story is, in some ways, even better. Cancelled after three years, it stayed alive through the urgent advocacy of a smallish group of dedicated fans, who quite simply wanted more. The wholly unexpected, globe-straddling success of Star Wars gave it a second life in the cinema; the popularity of the films led to Star Trek: The Next Generation; and the popularity of that show gave us a dizzying variety of spin-offs. Finally, when that seam appeared to have been thoroughly worked out, JJ Abrams went back to the original series and remade it with new, young actors as a big, bold, primary-coloured action film. Not everyone, I understand, has maintained contact with the show through its long and tortuous history. For the sake of the general reader, then, these are the show’s more popular incarnations: the original Star Trek series (1966-69), The Next Generation (1987-94); and the films, both ancient and modern. That’s not to say that Deep Space Nine (1993-99), Voyager (1995-2001) and Enterprise (2001-05) are inferior series, although some would say just that. (I would defend Deep Space Nine to the hilt. It took a while to find its way, but grew into a drama of epic scope and ambition.) But non-aficionados barely know them, and this is not the place to learn more than the basics.

By curious coincidence, I was finishing my book in the week that Leonard Nimoy died. Perhaps ridiculously, given that I came no closer to meeting him than to climbing Everest, I felt bereft at his passing, even though he had clearly lived long and prospered. What did surprise me, though, was that I wasn’t alone in this. There was a sense, in that week, that someone genuinely significant had gone, and with him a slice of our childhoods – or, if we’re going to be honest about this, our lives. On Facebook someone I know juxtaposed two stills from the original series. In the first, Kirk, Spock, Bones and Scotty are in the Enterprise meeting room discussing something of import. In the second, there’s a long shot of the same table and only Kirk is sitting there. Their vision of the future, we now realise, was an awfully long time ago.

Hurray, then, for DVDs and streaming services, for hard disks and for a culture that has grown to value the ephemeral telly rubbish of the distant past. Recently, I took the opportunity to introduce the original series in its remastered glory to my 14-year-old daughter, who had developed a taste for science fiction and fantasy that, in my own childhood, would not have been encouraged. She loved it, needless to say. My son, then 11, was less impressed: it was all a bit too talky and needed more action. He hopes one day to get a job as an NBC executive.

‘Set Phasers to Stun: 50 Years of Star Trek’, by Marcus Berkmann (Little, Brown, £13.99) will be published on 24 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments