Valerie Taylor: ‘You might be able to direct a dog , but you can’t direct a shark’

The pioneering conservationist tells Ashley Spencer about how she went from being a working-class spearfisher to filmmaker behind ‘Jaws’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

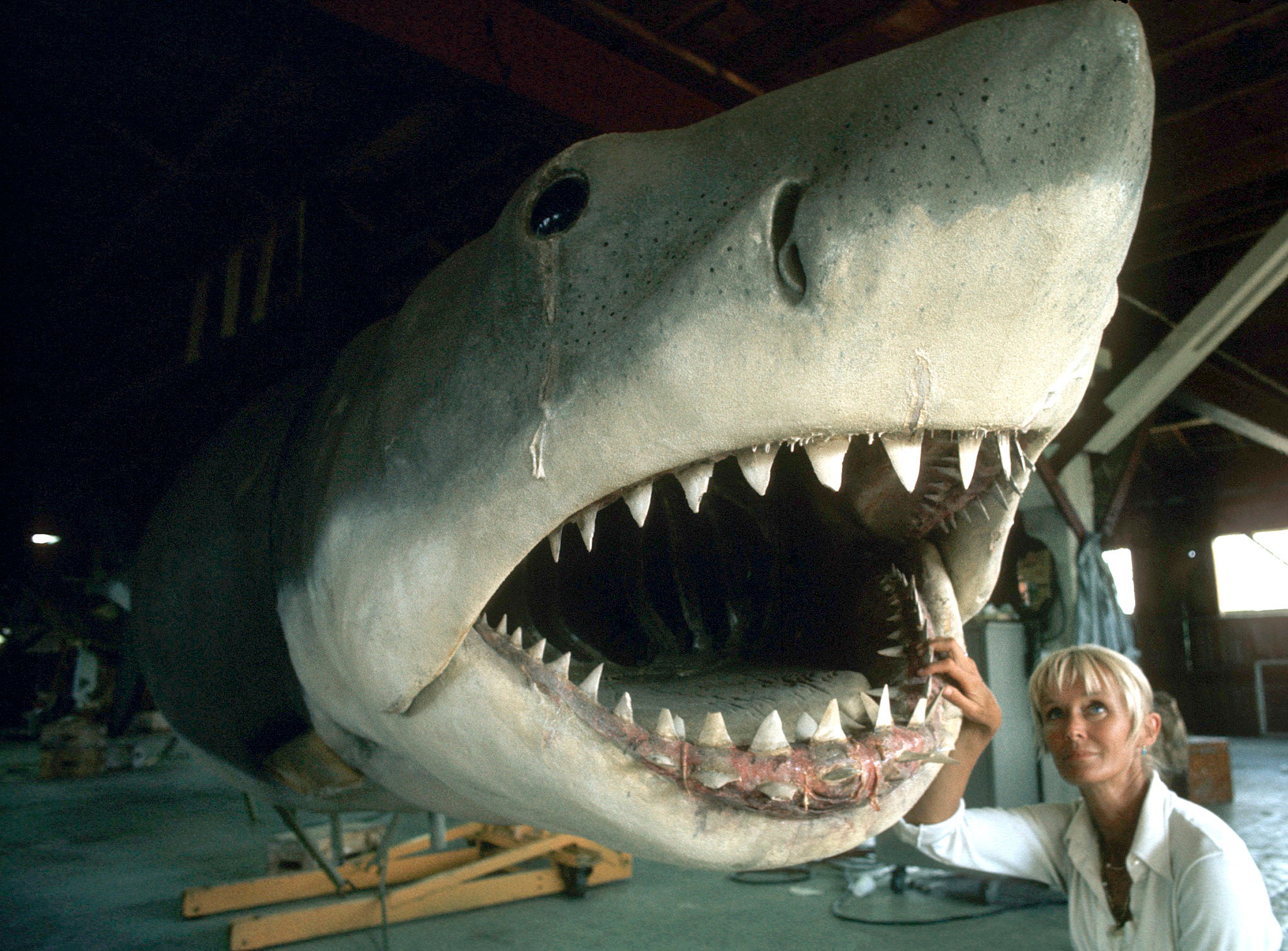

Your support makes all the difference.Steven Spielberg needed a real shark. Before the young director began filming Jaws with his famously malfunctioning animatronic beast off Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, he hired two underwater cinematographers to film great white sharks off the coast of south Australia.

Skilled divers and well known in their home country, Australian couple Ron and Valerie Taylor set off to capture the footage that would be used in the climactic 1975 scene in which Richard Dreyfuss’s Hooper, seemingly safe in a shark cage, confronts the monster terrorising beachgoers.

But, as Valerie Taylor, the subject of a new documentary, says in a recent video interview from her home in Sydney, “you might be able to direct a dog or a human or a horse, but you can’t direct a shark”.

It quickly became clear that the Taylors were battling two unwilling parties: the shark and professional stuntman Carl Rizzo, who didn’t know how to dive and panicked at being lowered in the cage. As he waffled on the boat deck, the shark approached, became tangled in the wires supporting the cage and ultimately snapped the empty container loose from the winch, sending it plummeting into the depths.

Ron filmed the whole thing underwater, while Valerie grabbed a camera on the ship and shot overhead. Spielberg was so enamoured of the footage of the unexpected turn of events, he had the script rewritten to accommodate it, altering Hooper’s fate from shark bait to survivor as the animal thrashed overhead.

Valerie Taylor’s work on Jaws is just one chapter in her incredible life, which saw her shift from lethal spearfisher to filmmaker and pioneering conservationist.

“She was like a Marvel superhero to me,” Australian producer Bettina Dalton says. “She influenced everything about my career and my passion for the natural world.”

That reverence led Dalton to team up with director Sally Aitken for the National Geographic documentary Playing With Sharks, which follows Taylor’s career and is now available on Disney+.

Born in Australia and raised mostly in New Zealand, Valerie Taylor, now 85, grew up poor. She was hospitalised with polio at age 12 and forced to drop out of school while she relearned how to walk. She began working as a comic strip artist, then dabbled in theatre acting, but hated being tied to the same place every day.

“I had a good mother. She said, ‘just do what you like. Try what you like. It can’t hurt you and you’ll learn’,” Taylor, her statement earrings swinging under her silver hair, tells me emphatically. When she began diving and spearfishing professionally, however, her mother was “horrified”. Valerie adds, “I was supposed to get married and have children”.

She did eventually marry. Ron Taylor, a fellow spearfishing champion, was also skilled with an underwater camera, and they began making films documenting marine life together. Valerie Taylor, with her glamorous “Bond girl” looks, became the focal point since they could fetch more money if she appeared onscreen. They were together until Ron died of leukaemia in 2012.

After she killed a shark while shooting a film in the 1960s, the Taylors had an epiphany: Sharks needed to be studied and understood, rather than slain

“Here’s this incredible front-of-house character, and here’s an amazing technical wizard,” Aitken says. “Together, they realised that was a winning combination.”

Not only did Valerie Taylor have a magnetic on-camera presence, but she had a rare ability to connect with animals, including sharks, which were then little understood.

“They all have different personalities. Some are shy, some are bullies, some are brave,” Taylor says. “When you get to know a school of sharks, you get to know them as individuals.”

After she killed a shark while shooting a film in the 1960s, the Taylors had an epiphany: Sharks needed to be studied and understood, rather than slain. They quit spearfishing entirely, and Aitken likened their journey from hunters to conservationists to that of John James Audubon.

“I have that sort of personality that I don’t get afraid. I get angry,” Valerie Taylor says. “Even when I’ve been bitten, I’ve just stayed still and waited for it to let go – because they’ve made a mistake.”

Still, she concedes, “I don’t expect other people to behave like I do”.

Her signature look, a pink wetsuit and brightly coloured hair ribbon could be seen as a defiant embrace of her femininity in a male-dominated industry, but it was also a simple way for her to stand out in underwater footage. “Ron wanted colour in a blue world,” Taylor says. “He said, ‘Cousteau has a red beanie. You can have a red ribbon.’ That was that.”

When asked, she shrugs at the idea that she faced additional challenges as the only woman on boats full of men for most of her life, especially in the Fifties and Sixties, when women were still largely expected to stick to traditional roles.

“I was as good as they were, so there you go. No problem,” she says. “And, although I didn’t realise it, I was probably as tough.”

The Playing With Sharks filmmakers, who pored over decades of media coverage and archival footage, describe Taylor as someone who faced an uphill battle on multiple levels but who was also seen as an intriguing novelty.

“Of course, she had to fight to be taken seriously,” Aitken says. “She was working class. She was someone who really had very little education. I think the culture saw her as extraordinary. That in itself can be a liberating path, precisely because you are singular.”

When Jaws became an instant, unexpected blockbuster in 1975, the Taylors realised that the movie was doing harm that they’d never considered: recreational shark hunting gained popularity and audiences feared that legions of bloodthirsty sharks were stalking humans just below the surface. In reality, there are hundreds of species of sharks, and only a few have been known to bite humans. Those that do usually mistake people for their natural prey, like sea lions.

“For some reason, filmgoers believed it. There’s no shark like that alive in the world today,” Taylor says. “Ron had a saying: ‘You don’t go to New York and expect to see King Kong on the Empire State Building. Neither should you go into the water expecting to see Jaws.’”

In an attempt to quell public fears, Universal flew the Taylors to the US for a talk show tour educating the public about sharks, and Taylor says, “I’ve been fighting for the poor old, much-maligned sharks and the marine world, in general, ever since”.

In 1984, she helped campaign to make the grey nurse shark the first protected shark species in the world. Her nature photography has been featured in National Geographic. The same area where she and Ron Taylor filmed their Jaws sequence is now a marine park named in their honour. And she still publishes essays passionately defending animals.

Yet, shark populations have been decimated around the world, primarily because of overfishing, and Valerie Taylor says that many of the underwater scenes she witnessed in her early days no longer exist.

“I hate being old, but at least it means I was in the ocean when it was pristine,” she says, adding that today, “it’s like going to where there was a rainforest and seeing a field of corn”.

Despite all that’s covered in Playing With Sharks, she says, “it’s not my whole life story, by any means”. There was the time she was left at sea and saved herself by anchoring her hair ribbons to a piece of coral until another boat happened upon her. Or the day she taught Mick Jagger how to scuba dive on a whim. (He was a quick study, despite the weight belt sliding down his narrow hips.) She also survived breast cancer.

Though she still dives, her arthritis makes being in the colder Australian waters difficult, and she’s eager to return to Fiji, where swimming feels like “taking a bath”.

“I can’t jump anymore, not that I particularly want to jump,” she says. “But if I go into the ocean, I can fly.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments