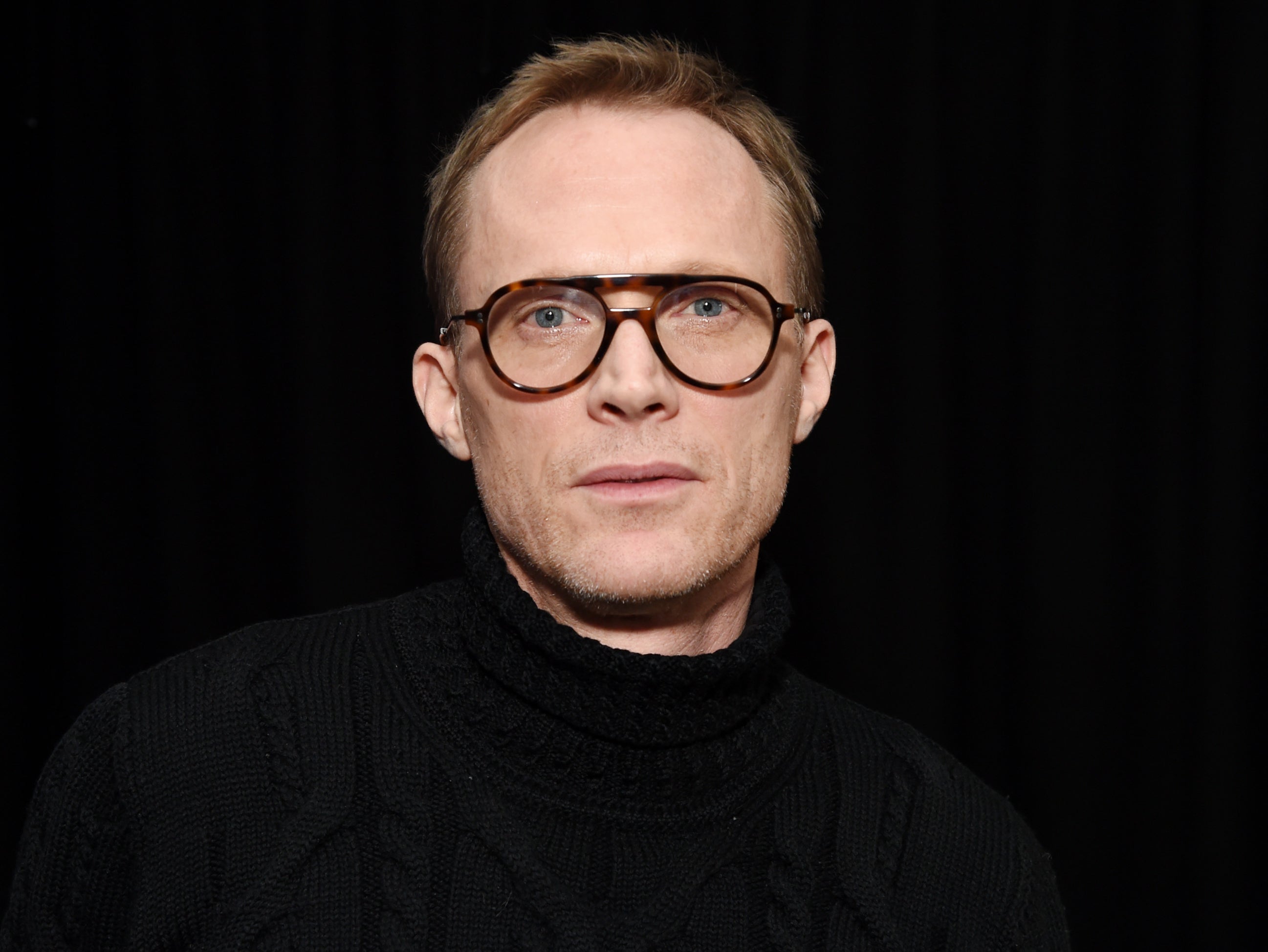

Paul Bettany: ‘I’m 50 years old now and still keeping these wounds fresh’

The actor won an Emmy for his robot role in Marvel’s ‘WandaVision’ but he’s always been better suited to more sinister roles. As he stars as the arrogant Duke of Argyll in BBC’s ‘A Very British Scandal’, he talks to Annabel Nugent about self-doubt, death, his period of homelessness and a fair few tabloid scandals of his own…

Some actors know they’re destined for great things, but Paul Bettany was never so sure. The actor insists that he has always lacked self-belief compared to, say, his late A Knight’s Tale co-star Heath Ledger, who possessed it in such joyful abundance. Yet Bettany says this with so much of that jammy English charm that it’s hard to truly believe him. “So much has been spoken about Heath’s darkness but I only saw this person who was so full of light and had this confidence in himself that was magnetic but never felt obnoxious,” he recalls, ruefully. “You just knew he was a star.” On the other hand, he says half-laughing, custard-coloured beanie on his head, “I’m still filled with absolute self-doubt all the time.”

Bettany didn’t actually set out to become an actor. Music had once been the goal. “But I hated singing my own songs in front of people. It felt very revealing and I didn’t like it.” He soon realised that with acting, there was a desirable buffer between himself and the truth, and enrolled in drama school. Films followed shortly after. A lead part in the 2000 British film Gangster No 1 was the diving board for Bettany’s plunge into Hollywood. A year later, A Knight’s Tale and A Beautiful Mind introduced the Harlesden-born actor to international audiences.

His breakout role as a ruthless, suited and booted gangster left an impression. Bettany was convincing as a pretty boy who could kick your teeth in. But it’s his distinctive browless-ness that has often undercut the actor’s more obviously Hollywood attributes, which might’ve seen him pursue a less interesting career.

Early on, his look lent itself to roles with religious overtones. Most famously, there was Bettany as the cowled monk in The Da Vinci Code. He also played a gun-toting archangel in Legion and a vampire hunter in the dystopian horror Priest, as well as an actual priest opposite Willem Dafoe and Tom Hardy in The Reckoning. 7

More recently, though, he has split from scripture to play a character that does away with eyebrows altogether, caked as they are in layers of red paint when he is portraying a lovable Marvel android. Vision was initially a voice role in 2008’s Iron Man before Bettany parlayed it into an Emmy-nominated performance in the studio’s first TV series, WandaVision, this year.

But sweet, kind-hearted Vision is the exception on Bettany’s CV and his next role is “a bit of a palate cleanser”, he says. In the Boxing Day BBC drama A Very British Scandal, he plays the Duke of Argyll opposite Claire Foy’s Duchess, whose notorious divorce trial made sensationalist headlines in the Sixties. Bettany gives a brilliant performance as the Duke, whose arrogance and charm he captures with the right mix of subtlety and cunning. And when those qualities curdle into cruelty, he plays it with teeth. At the Duke’s goading, Foy’s Duchess is hounded by the British press who unpick the sinews of her private life with demonic glee.

Bettany has had his own run-ins with intrusive media. “Here’s an example for you,” says the actor, whose anecdotes come fast and looping. “Years ago, me and Jennifer” – his wife, Academy Award-winner Jennifer Connelly – “were having an argument on the subway about who was picking the kids up from school”. He had meetings; she had yoga. Someone recorded the fight and it soon transpired that the couple were splitting up, at least according to People magazine. “Someone at my kids’ school asked them if they knew their parents were getting a divorce,” he recalls, reenacting his disbelief: eyes wide, mouth agape. “I don’t feel that I signed some Faustian pact with the devil when I became an actor to give away all my privacy,” he says firmly.

All eyes are on him now more than ever. With his recent roles in WandaVision and as the menacing Dryden Vos in Star Wars, Bettany is part of two of the biggest franchises in the world, a bankable star. There was a time, though, when his career had gone almost terminally cold.

“I finished filming [the 2004 romantic comedy] Wimbledon and my baby was just born so I decided that I was going to take two years off,” he says. By then, Bettany was on track for what seemed like an inevitable ascent. Surely, he could afford to take his foot off the pedal for a moment. It turns out that he couldn’t. When he came back, people had moved on. “It was hard to find work,” he says; “then the financial crash happened and I made a lot of decisions that were based on ‘Holy s***, I have a mortgage. I have two kids. I gotta make money’.”

Bettany doesn’t specify exactly what these decisions were, but a scroll through his IMDb during this period throws up credits in poorly received films including Broken Lines, The Secret Life of Bees, Inkheart, Creation, The Tourist and Legion. Bettany, however, would like to point out that there are only perhaps 10 actors in the world who get to choose their films. “Daniel Day-Lewis is one and Meryl Streep is another”. The rest of us, he chuckles, mostly take the next project on offer.

He realises now that some of these choices “denigrated the brand” and made it that much harder to get work. In 2013, when a big-time producer told Bettany he’d never work again, he was disheartened enough to believe him. But this kind of career upheaval had its benefits, too. “It’s made me not take work for granted so much. And I’m a bit more relaxed,” Bettany says. “You just don’t know what’s going to happen next so just f****** relax about it.” Words to live by. “Anyway, life is curly,” Bettany smiles, “and I got very lucky.”

Some of that success comes down to plain anatomy. Bettany is tall. Movie- star tall. All six feet and three inches of him are coiled in a chair, poised to spring to life and reveal a towering superhero frame. He speaks quickly, in between pauses so long you’d swear the screen was frozen as he gazes out a window. These breaks in conversation, though, don’t feel like someone self-censoring; rather, he is careful about gathering his words, actively wrestling against his impulse to put walls up. “I think because of the way the media works, one tends to be more guarded. I really try to fight against it when doing press. I just try to be myself, otherwise,” he adds a little sadly, “it’s an incredibly alienating experience.”

Unlike Day-Lewis, he wouldn’t call himself a method actor. But he admits to one method that sounds more torturous than any radical body transformation. When Bettany was 16, living with his family in Hertfordshire on the campus of an all-girl boarding school where his father taught drama, his eight-year-old brother Matthew died. It was a tragic accident.

“It exploded our family,” he says, turning expectedly grave. “I had a real psychological break there.” Now, when he needs to summon sadness he’ll think of Matthew. He’ll bring “a piece of memorabilia” to set, like his sibling’s old sweater, and bundle it up somewhere near the camera, so that it’s in his eyeline but out of the shot. It’ll make him sob. Bettany knows it isn’t healthy. “It’s madness,” he concedes. “I’m 50 years old now and still keeping these wounds fresh.” He’s adamant that it’s not part of some lofty, suffer-for-the-art premise. “I do it – and I really do mean this – because I’m just not good enough to do it imaginatively in the moment”.

The result is often painful to watch. Viewers praised Bettany’s affecting performance in WandaVision’s final episode, in which his character muses on the purpose of grieving (“What is grief if not love persevering?”). Bettany convinces you he’s feeling something because he really is. The actor confesses his process is getting harder with age, however. “I used to be able to do it and then go out clubbing,” he says. These days a script will come along, which requires this kind of self-flagellation and he’ll consider it carefully “because I know that it’s going to be a couple of days spent digging myself out of that feeling”. He recalls being able to bounce back much quicker. He wonders aloud whether “it’s like how old people bruise more”.

Bettany was badly bullied at school. “I hated school. I wasn’t very good at it.” The bullying started when he moved from London to Hertfordshire where he attended Chancellor’s School. “It felt very rural to me and I don’t think I adapted very well,” he recalls. “My godfather was gay and it turns out – I didn’t know it at the time – but my father was also gay. I refused to take part in that boys’ school homophobia and consequently became incredibly bullied for being gay.”

He remembers being urinated on by his peers in the showers after football practice. “I would go hide in the deputy headmaster’s room because it was untenable for me to be out in the playground, or whatever.”

Bettany does this often; unfurling in surprising, often devastating candour only to brush it off with a casual word. Like a hand waving away a bad smell. After his brother’s death, Bettany dropped out of school. Then his memory “goes a bit hazy” but he was, for all intents and purposes, living on the street.

Can you imagine what it would be like, honestly, to have a bunch of lawyers go through every one of your emails and texts for 10 years?

As a teenager, Bettany would occasionally sleep on park benches but most of the time, he’d crash on the floor of his sister’s boarding house. “At the time I never would have described myself as homeless, but since working with homeless charities, they’ve wanted me to call it that,” he says. “How do I clarify this? I was without a home but I never felt homeless.”

The experience stayed with him, however. In 2014, Bettany made his directing debut with Shelter, a drama about homelessness starring Connelly opposite his Marvel co-star Anthony Mackie. “I didn’t want to trade on my own experiences to publicise it,” he says. But then he read an article headlined something like “‘Paul Bettany scripts film about homelessness from his $8m apartment in New York City’”. He feigns a tortured look. Behind him a sliver of that “$8m apartment” beams in through a wide door frame. A metal chandelier throws warm light upwards onto beautiful mouldings that crawl across the ceiling in geometric patterns. And yet he never hit back against those headlines. “I knew there was a really simple way of navigating that accusation, but I just didn’t want to take it because the f****** film was about empathy!”

You can expect that those brand-conscious Marvel bosses were thrilled as Bettany hit the headlines again last year, when the actor was pulled into Johnny Depp’s libel case against The Sun. Depp, with whom Bettany has worked on three films, sued the newspaper over its description of him as a “wife beater” in his relationship with Amber Heard. Texts exchanged between the two actors in 2013 were read aloud in court. Some of the messages were obscene and graphic. They joked about drowning Heard as a means to prove she wasn’t a witch. A barrister on the case referred to Bettany as Depp’s “drug buddy”. Unsurprisingly, Bettany is cautious speaking about it now. He smacks his lips and takes a moment. “I think that’s a really difficult subject to talk about and I think that I just pour fuel on the fire,” he finally says, before retreating into another long pause.

Although Bettany’s publicist interrupts to offer him a way out, he forges on. What he will say on the subject is that having his private messages aired in public was a peculiar experience. For Bettany, it shattered his notions of privacy. For others, the nastiness of the texts shattered any preconceptions of the actor. “It was very strange. It was a strange moment,” he says, halting again for what feels like an eternity. “What was strange about it was you suddenly have one of the most scabrous newspapers in London and their lawyers pouring through your texts for the last 10 years. Can you imagine what it would be like, honestly, to have a bunch of lawyers go through every one of your emails and texts for 10 years? All I can tell you was that it was an unpleasant feeling.”

Unpleasant is certainly one way to describe it. Although Bettany has spent decades living stateside, the actor’s continued fondness for understatements remains a mark of his staunch Britishness. He moved to New York in the Nineties and has lived there since (“I fell in love with an American by mistake”).

Next February, though, he’ll be back in London and playing NYC artist Andy Warhol in the Young Vic’s production of The Collaboration. It’ll be his first time treading the boards in 25 years. On the verge of his homecoming, the actor is very much the same unsure twenty-something who left the city to pursue acting. But he sees the value in it now. “I’ve never, ever felt confident about anything I was about to do or have just done,” Bettany says. Only this time he’s grinning.

A Very British Scandal airs on 26 December at 9.00pm on BBC One

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks