Netflix documentary Athlete A asks, ‘What is the cost of winning?’

Netflix's brilliant yet devastating expose of abuse at top-level gymnastics shows that athletes were disposable machines geared to win medals and sell cereal sponsorship deals, writes Annie Lord

There’s a scene in Netflix’s Athlete A that I had watched years before. At the 1996 Olympics, USA gymnastic team member Kerri Strug falls from a vault, tearing two ligaments in her ankle. In order for the US to win gold, she has to go back around and execute the vault again, this time perfectly. So she crawls off the mat, watery-eyed and limping, and goes to the starting marker again. “You can do it!” shouts her coach Béla Károlyy. Miraculously, Strug does, her tiny body spinning and snapping through the air, all straight lines and sharp angles.

Watching the vault again, in the context of Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk’s brilliant yet devastating expose of abuse at top-level gymnastics Athlete A, I witnessed something very different than I did the first time. No longer was it grit and determination that I saw, but fear. The way Strug collapses on the floor after the movement, her face distorted in pain; how she’s carried away in a cast. “All I could think was: Why are we celebrating this?” says Jennifer Sey, author of Chalked Up: Inside Elite Gymnastics, as she narrates the sequence. “Don’t pretend she had a choice. She was not going to do anything but do that vault. This is a competitive country. We consider ourselves the best in the world at everything, right? But this notion that we would sacrifice our young to win. I think that disgusts us a little. We would never discuss that.”

Sacrificing young people in order to win is the uncomfortable yet necessary subject matter that Athlete A seeks to interrogate. At the surface, the film looks at how over two decades Dr Larry Nassar sexually assaulted around 500 women in his care under the guise of medical procedure. But it also digs deeper into the ways those high up at USA Gymnastics, such as its president Steve Penny, turned a blind eye to abuse in order to protect the organisation’s brand. To men like Penny, girls were machines geared to win medals and sell cereal sponsorship deals. They were disposable, but medals and money were not.

With a fierce, unrelenting eye, Athlete A shows how the training techniques that produced champion gymnasts also made the girls vulnerable to abuse. As they defected from the Eastern Bloc to become the US Team coaches, Bela and Marta Karolyi brought with them a merciless system of discipline and punishment perfected under the oppressive Ceaușescu regime. In 1976, their training methods had produced Romania’s premier cultural export, the 14-year-old Olympic gold medal winner Nadia Comăneci, and now they were applying the same techniques in the “land of the free”. Gymnasts were moved to an isolated training camp in Texas away from their families, slapped if they fell short of perfection, called “pigs” if they gained weight. Under these brutal coaching methods, the line between training and child abuse became so blurred, many gymnasts were unable to recognise what was inappropriate and what was a necessary part of becoming an Olympian.

Strug and girls like her were not a priority for Penny. Getting those same girls on T-shirts, low-fat crisp packets, and fruit juice ads was. Kids across America were desperate to copy those swishy ponytailed, smiling girls with pointed toes who were so often drenched in gold. With USA Gymnastics burning through 12 million dollars in revenue by 1991, the sport was a cash cow and one that Penny wanted to keep milking. So when his athletes, the one’s whose job it was to protect, told him about the sexual abuse, what followed were non-disclosure agreements, cover-ups and intimidation. Athlete A gets its name from the moniker served to Maggie Nichols – the first girl to report Nassar to USA Gymnastics. Despite being described as a “shoo-in” for an Olympic team place, soon after reporting her numerous sexual assaults, Nichols didn’t even make the reserves.

Sports documentaries often romanticise the almost pathological desire to win possessed by so many athletes and their adjacent organisations. On Netflix series The Last Dance, during his second season with the Bulls, Michael Jordan plays through an injury that has a 10 per cent chance of ending his entire career. Coach Buddy Stephens of Last Chance U is so determined for East Mississippi Community College’s American Football team to win the league that he punches a referee. In Cheer, the Navarro College Bulldogs Cheer Team tumble from the top of mammoth pyramids with ankle sprains and wrist pain, because risking broken bones and paralysis is better than disappointing their coach. After watching Athlete A, I reconsidered the cost of winning. What is an acceptable amount to pay? Millions? Time with family and friends? A young woman’s life? When do you stop screaming more and ask: Should we stop? Are you okay?

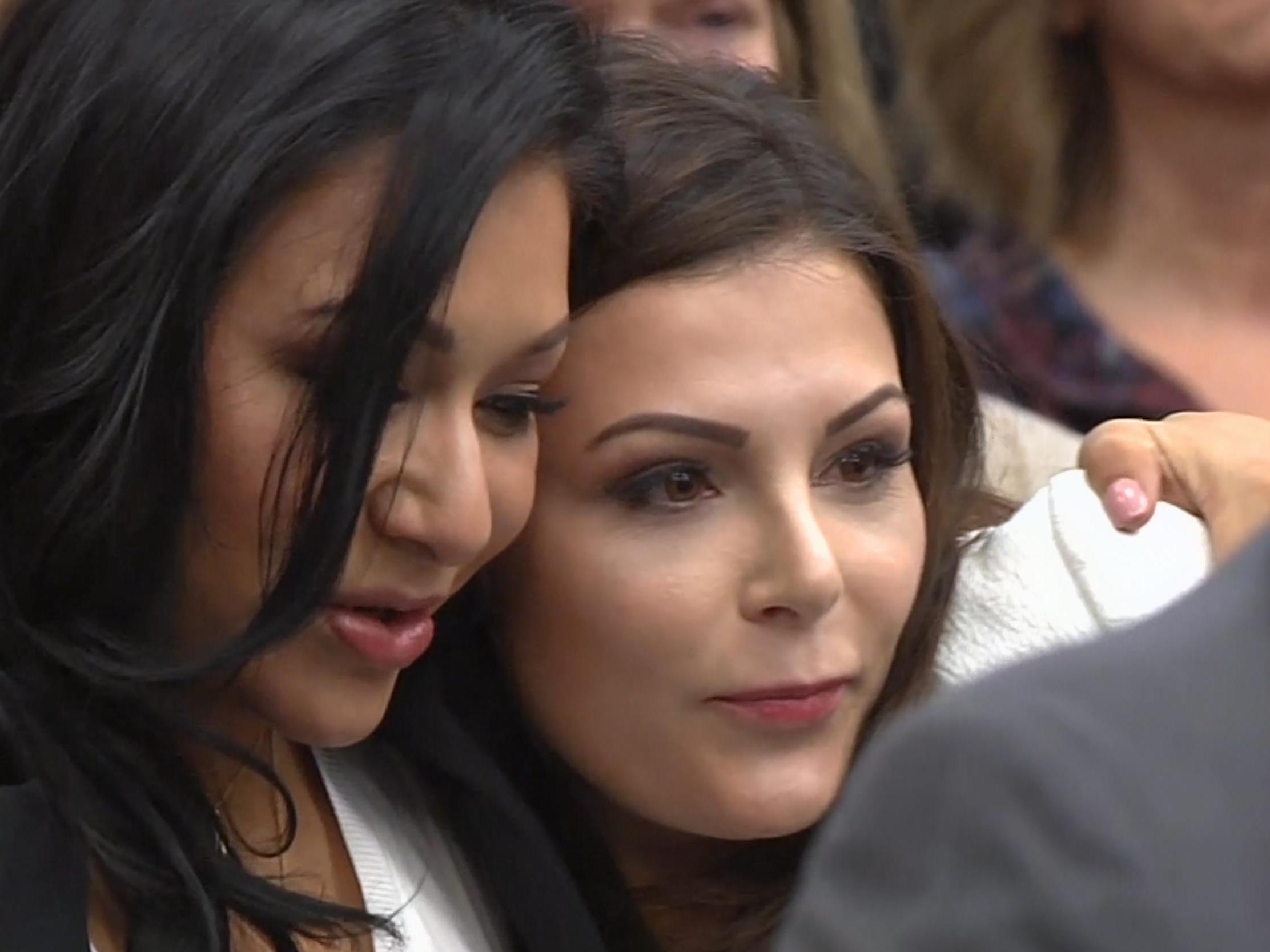

Through the work of investigative journalists at the Indianapolis Star and a strong prosecution team, Nassar was eventually convicted. He will remain in jail for the rest of his life. The documentary shows footage from the moment in court when survivors were allowed to stand up and address Nassar. “You pretended to be on my side,” 2000 Olympian Gymnastic team member Jamie Dantzscher told him. “You knew I was powerless.” I cried listening to these women’s stories.

Nassar might have robbed Nichols of her chance to be on an Olympic team. But now she plays gymnastics at Oklahoma University, where she just became the NCAA Gymnastics Champion. “Elite gymnastics does kind of beat me down, as a person, as a woman,” Nicols says before the end credits roll. “I’ve found my love for the sport again.” Even if Nichols never got another medal, she’d still be winning.

Athlete A is streaming on Netflix now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks