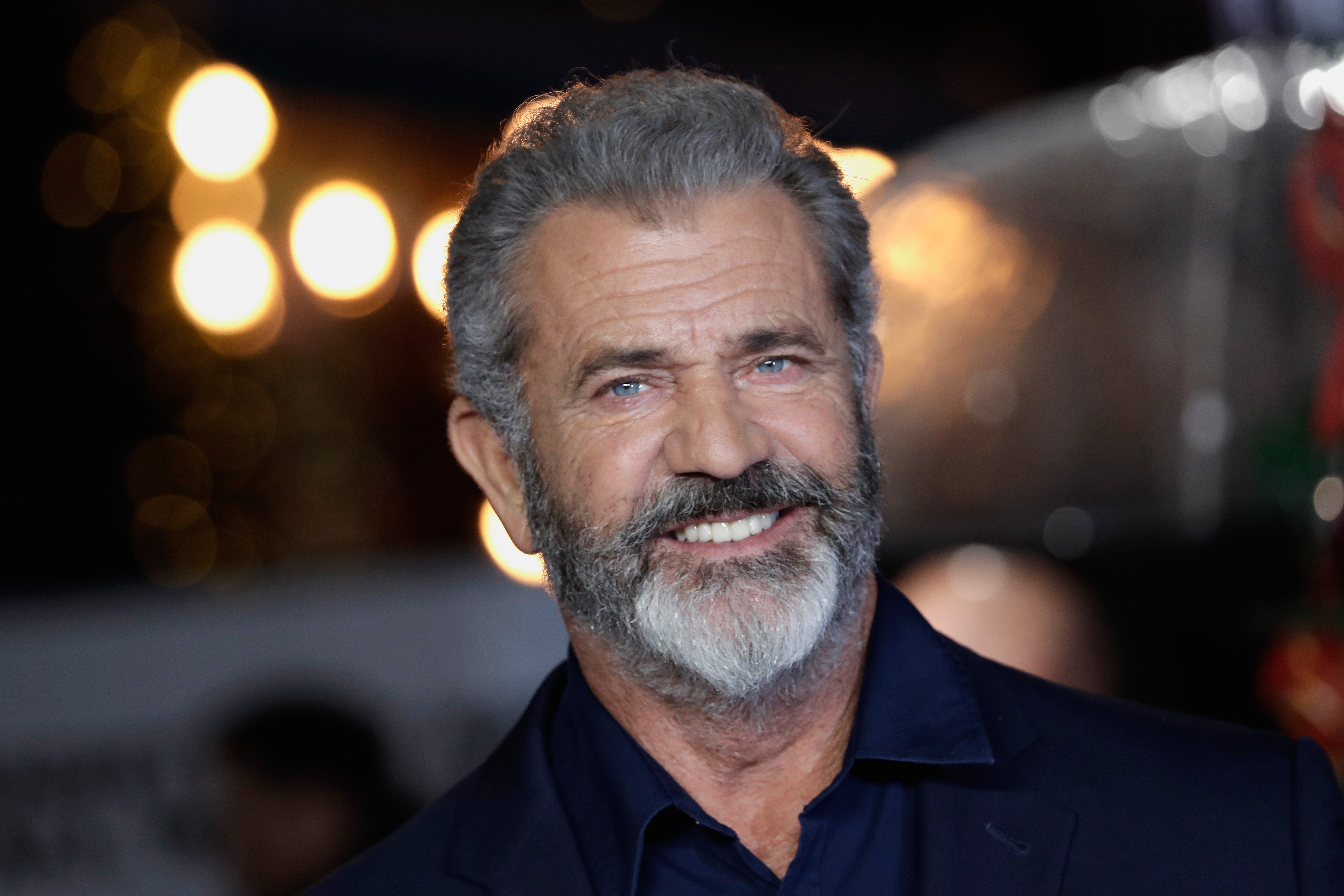

Hollywood loves the three-act structure – that’s why it’s resurrecting Mel Gibson

The troubled actor has gone from Eighties beau ideal to problematic lead star, with his legacy tarnished by accusations of domestic violence, homophobia and antisemitism. But perhaps it’s not so surprising that Tinseltown is letting him in from the cold, writes Laura Barton

For those whose knowledge of Mel Gibson’s career trajectory might have waned, let me offer a brief refresher: for a time, Gibson was the Eighties beau ideal. His image was one of charming meathead, rogueish aspirant; an actor with gleaming pectorals and beaded brow, undaunted at the prospect of playing Hamlet.

Gibson, whose early years had been split between America and Australia, forged an early reputation as the loveable hero of the Mad Max and Lethal Weapon franchises, before starring in historical battlefield dramas Braveheart and The Patriot, romantic comedy What Women Want, and science fiction corn circle thriller Signs, among many others.

Perhaps the first inkling that anything might be awry was his determination to direct 2004’s The Passion of the Christ, an epic account of the passion and death of Jesus Christ, shot in Aramaic, Latin and Hebrew and originally intended to screen without subtitles. The film was hugely successful at the box office, but its portrayal of Jewish characters led Gibson, a Catholic, to be accused of antisemitism.

The years that followed were a muddling of professional success and personal dismantling. A drunk driving arrest, a divorce from his first wife (and mother of his seven children), a second marriage, and a domestic violence claim including incendiary voice recordings of the actor threatening his new wife.

Over the years, he had made derogatory comments about homosexuals, African Americans and Jews. There was ongoing addiction, rehab, a growing sense of volatility and uncomfortable political and religious views. Hollywood backed away, effectively blacklisting Gibson in 2004.

The nominations (among them six hat-tips from the Academy Awards) that greeted his 2016 war epic Hacksaw Ridge were regarded as something of a thawing in his relationship with the wider cinematic world. But this was another Gibson directing effort, and although there had been acting roles across the exiled years, it perhaps seemed safer if the star now remained behind the camera, less visible, less vocal.

And so, news that Gibson will return to our screens, taking a high-profile role in the new John Wick TV series has surprised many. But there he was, featured prominently in the trailer for The Continental this week, in his role as an underworld kingpin and manager of a New York hotel for assassins.

Despite the social and political shifts that have occurred since Gibson’s heyday and demise, we should not have been shocked to see him welcomed in from the cold. The rehabilitation of fallen cultural heroes is a familiar story.

Robert Downey Jr, once caught in his car with heroin, cocaine and an unloaded gun (among other misdemeanours), later saw his career flourish; Hugh Grant, once snagged in his car with a sex worker, was allowed to redeem himself. Cheryl Cole went on to have success in music and TV despite a conviction for racially aggravated assault during the early days of Girls Aloud. See also the career arcs of Charlie Sheen, Tiger Woods, Dave Chappelle. At the time of writing, it seems likely that the careers of Johnny Depp and Kevin Spacey might follow a similar path.

We apply the tale of heroic fall from grace and ultimate redemption everywhere

Of course, some celebrities remain unrestored – Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, and R Kelly among them. In such instances, the magnitude of their crimes was too great or too calculated, or the level of their remorse was deemed too small. For a star to be rehabilitated, we expect a sincere apology and a sense of responsibility for their actions. Gibson, for instance, has since labelled his antisemitic remarks “despicable”. “[I] said things I do not believe to be true…” he insisted in a statement following his 2006 DUI arrest. “I am deeply ashamed of everything I said.”

Regret is an essential step on the road to a celebrity’s salvation. We are, after all, creatures of narrative, and the most familiar narrative of all – one used from romcoms to horror movies, ancient myths to fairy stories, novels to plays to television soap operas – is that of the three-act structure. We carry it within us; it gives us purpose and meaning and order in a chaotic world.

A crucial point in this narrative structure comes, traditionally, at the end of the second act, when the action has risen and risen and risen, until the worst possible thing that could happen to our protagonist duly happens. To reach the third act, they must pass through a long dark night of the soul before they are allowed, apparently transformed and somewhat chastened, to triumph again.

A similar notion is famously explored by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Here, all steps will lead our protagonist to the abyss, and then to a kind of confrontation and atonement. “It is by going down into the abyss that we recover the treasures of life,” Campbell said. “Where you stumble, there lies your treasure.”

The power of this familiar narrative has broader ramifications of course. Subconsciously, we apply its tale of heroic fall from grace and ultimate redemption everywhere – to film stars, footballers and politicians. Arguably Ronald Reagan, who began as a Hollywood actor, framed his two terms as US president according to this structure – his lowest approval ratings coming in that long dark night before his re-election campaign of 1984. At this current moment, we might assume that Donald Trump is deep in the abyss; but there is a danger in assuming that he will not rise again for a third act.

In the case of Gibson, we might wonder whether he sees a parallel in the story of The Passion of the Christ – after the crucifixion, and the burial, his career is resurrected. For the Hollywood studios and their audiences, perhaps there is a feeling that the hero has been cast out long enough; his character has evolved, lessons have been learned, and the treasure has been found. Or perhaps they simply need one of their highest-grossing stars to rise again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks