Making a Murderer Part 2: Returning to the scene of the crime that gripped the world

Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi, the directors of the Netflix phenomenon, discuss how everything changed for their second series

When, more than a decade ago, Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos first visited Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, to begin shooting what would become Making a Murderer, they were graduate film students at Columbia University. “We could play that card a little bit: ‘Oh silly us, we’re just making this thing!,’” they say. It was a ruse that allowed them to slip quietly into the epicentre of one of the strangest, most perplexing criminal cases to have gripped America in years.

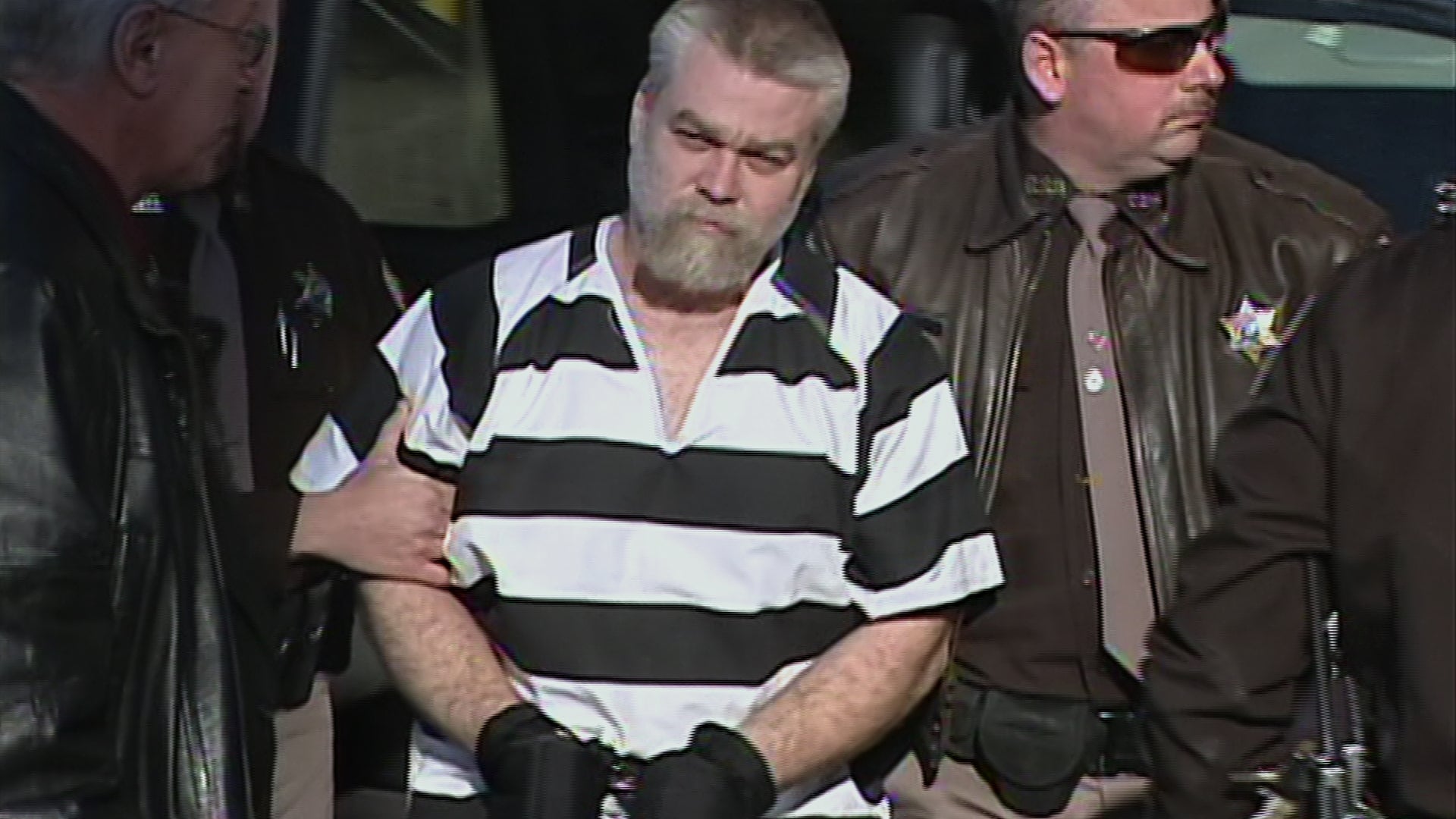

The resulting Netflix documentary series – which first aired in 2016 and took 10 years to make – follows the story of Steven Avery, who was given a 35-year sentence in 1985 for a rape he didn’t commit. After serving 18 years, Avery was exonerated in 2003 by DNA evidence, and began the process of suing the county for $36m (£27m) – only to find himself accused two years later of the murder of 25-year-old photographer Teresa Halbach, whose remains were found at his family’s salvage yard.

Over 10 episodes, the series covered Avery’s arrest, the – arguably coerced – confession of his 16-year-old nephew Brendan Dassey, who has learning difficulties, and the trial and eventual life imprisonment of Avery and Dassey.

Arriving at a point when the public were hungry for true crime – an appetite bolstered by the success of shows like The Jinx, and podcasts such as Serial – Netflix’s Making a Murderer lit a cultural firestorm. Millions watched; hundreds of thousands of people signed a petition calling for the release of Avery; and just about everyone had an opinion on whether he was guilty or, as his defence lawyers implied, framed by disgruntled Manitowoc police.

Overnight, the Averys and Dasseys went from being locally vilified criminals to worldwide celebrities. Avery’s defence lawyers – Dean Strang and Jerry Buting – became “heartthrobs”, and the state prosecutor Ken Kratz began giving interviews to every news outlet that would have him. When Ricciardi and Demos returned to Manitowoc to film Making a Murderer Part 2, which lands on Netflix on Friday, “it was not the same world”.

“Part 2 takes place a lot more behind the scenes,” says Demos, “but for some of the more public events, we had to make the decision: are we gonna go? If we went, would we be become part of the story? If the media were there, would they turn the cameras on us?’” Despite the fact they didn’t appear in the first season, Demos and Ricciardi became so recognisable they found themselves having to brief their crew and send them into battle, “without physically being there ourselves”.

It was frustrating, but they knew it was a sign they had succeeded. “There was such a tremendous response,” says Demos. “Our goal had been to start a dialogue, and it was amazing to us that now people were talking.”

It was thanks to this dialogue that Avery – who had run out of money and was fruitlessly attempting to represent himself from prison – attracted the attention of Kathleen Zellner, one of the most successful post-conviction attorneys in the US. Part 2 follows Zellner, who has overturned 17 wrongful convictions over the course of her career, in her obsessive quest to get to the bottom of what happened and to exonerate Avery. “If he’s guilty,” she says, “I’ll fail.”

While Dassey’s appeal – spearheaded by Laura Nirider and Steven Drizin of the Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth – is “essentially a battle of interpretation of what played out in that [interrogation] room,” Avery’s requires Zellner to conduct a thorough, sometimes unsettling, reinvestigation of the crime.

She covers a female mannequin with fake blood and has her assistant chuck it into the back of a car, over and over again, so she can observe the blood splatter. She places an array of hammers and knives on a table, and asks an expert to talk her through the most likely murder weapon. She contacts witnesses, and has them drive her around the vicinity of the alleged murder scene to recreate what they saw. “They’re gonna regret the day they planted the evidence,” she says – referring to the authorities – with a steely look in her eyes.

“What’s interesting about her,” says Ricciardi, “is that she’s not only a private, post-conviction attorney who keeps winning, but that with every wrongful conviction she got overturned, every single one of her clients walked. None of them was retried.”

“And in approximately half the cases,” adds Demos, “she also solved the crime. So the motivation is not just to help her clients, it’s a broader social good that she thinks she’s adding. What you learn in this series is yes, she’s working for Steven Avery – and she’s his advocate – but she talks as much about working for Teresa Halbach, and wanting to find out what happened to her. Because if the wrong person is in prison, it means the guilty person is out free.”

Though the directors insist they never wanted to glorify or sensationalise the “horrific murder” around which the show revolves, but simply to expose flaws in the US justice system, they have been criticised by Halbach’s family for “creating entertainment and seeking profit from our loss”.

It’s easy to understand the family’s discomfort. During our conversation, Demos and Ricciardi refer to the “story”, the “characters”, and the “drama” of the murder case. Amid the media circus, the reality of Teresa’s life and death risks being forgotten. “I guess I would say I understand why they’re saying what they’re saying,” concedes Demos, “but I’m also disappointed that that’s how they feel. Because we believe that asking questions is not a gesture of disrespect, but in fact the opposite. I hope that after Part 2, which asks questions in the most respectful way we can, that becomes clearer.”

They’ve been criticised too, by the numerous “armchair detectives” who have cropped up in the show’s wake, for omitting certain pieces of evidence – such as Avery’s “sweat” DNA, found under the hood latch of Teresa’s now-famous Toyota Rav4 – from the final cut. Prosecutor Kratz claimed the original series “twisted and misrepresented the truth”. Jodi Stachowski, Avery’s ex-fiancée, insisted it was “full of lies”. Did the directors feel the urge to defend themselves against such criticisms?

“We did know that there was a misunderstanding about our process,” says Ricciardi. “We welcome the opportunity to try to clarify, but we would also hope that people wouldn’t jump to conclusions. We have a clear storytelling process, and what ultimately made the cut were things that were relevant to the story we were telling.” When it came to presenting the prosecution’s case, “we were taking our cues from the state, and what Ken Kratz himself was claiming to be his most powerful evidence”.

Besides, those unhappy with the details left out of Making a Murderer should be more satisfied with Part 2. “Kathleen Zellner herself,” says Ricciardi, “in her process of wanting to deconstruct the state’s case, takes on a particular piece of evidence that didn’t make our cut, so we’re able to include it now.”

Ultimately though, those focusing solely on Avery’s guilt or innocence might be missing the larger point the show is trying to make – that the US justice system is failing its people. “We didn’t have a stake in his guilt or innocence,” says Demos. “The question really was, ‘How is the system going to treat him? How is this prosecution gonna go?’ Because we know how it went 20 years earlier.”

Still, they understand viewers’ frustrations. “We certainly recognise that we left them with a lot of questions,” laughs Demos. “We were challenging people to accept ambiguity, and we’re human beings too, we understand that that’s a difficult place to be. People crave answers.”

Will Making a Murderer Part 2 provide those answers? “The one thing you learn,” says Demos, “is don’t think you know what’s gonna happen.”

Making a Murderer Part 2 begins on Netflix on 19 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks