Louis Theroux: ‘Straight white men like me have been monopolising the conversation’

The documentarian has spent more than 20 years profiling some of the most dangerous people, but is now turning to executive producing with ‘The Bambers: Murder At The Farm’. He talks to Alexandra Pollard about anxiety, his unorthodox interview style and hearing playground rumours about Jimmy Savile

Hours before my conversation with Louis Theroux, he was doing a Joe Wicks workout in the back garden. “It’s become annoying to my wife Nancy, so I have to pick my moments where I’m not in her way,” says the 51-year-old now, his voice pitched, as it so often is, somewhere between dry and dejected. The garden was a first. It didn’t go well. “I got a bit self-conscious that someone might be videoing me through their window, looking like a loon doing mountain climb in my pyjama bottoms, and posting it on social media.” He sighs. “But that’s the price I’d be willing to pay.”

To be fair, he’s been filmed doing stranger things. In his two-and-a-half decades’ worth of documentaries, which began with Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends, Theroux has put himself in all sorts of bizarre, uncomfortable, sometimes dangerous situations: he’s auditioned for a porno; held a tiger; had liposuction; fired guns; attended a sensual eating party. He’s spent time with serial killers and survivalists, neo-Nazis and swingers, polygamists and drug addicts.

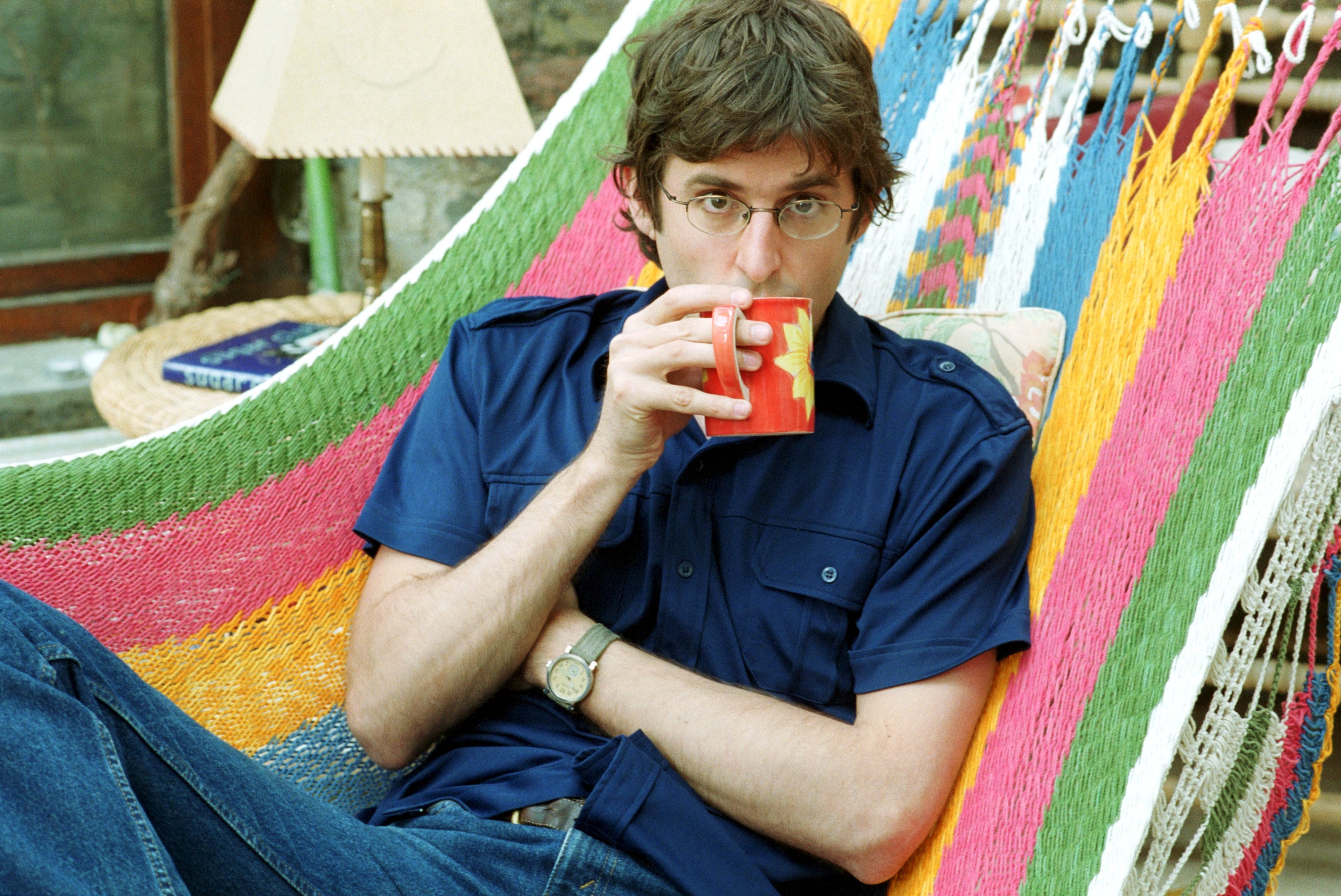

A gawky and bespectacled Englishman, he has immersed himself in the extremes of society, his mild awkwardness a front of sorts, behind which is a shrewd interviewer. Not feeling remotely threatened, his subjects let down their guard and reveal their deepest, darkest secrets (a famous exception was children’s TV presenter and serial sex offender Jimmy Savile, but we’ll get to that later). I would call him a wolf in sheep’s clothing, but it’s not as sly as that. He just has a sincere desire to understand people. When the pandemic rendered travelling impossible last year, he brought his gentle interrogation skills to the world of podcasts, hosting an intimate interview series called Grounded. Among its guests were Michaela Coel, Helena Bonham Carter, Rose McGowan and FKA twigs, who made headlines when she spoke in detail about her alleged abuse at the hands of actor Shia LaBeouf.

His shtick was once more naughty schoolboy than faux-naif, though. He started his career in the early Nineties, when he was hired to do segments for the filmmaker Michael Moore. I found an old, fuzzy clip of Theroux, aged 25, browsing through Ku Klux Klan merch with the organisation’s national director. At one point, he picks up a lighter. “Could be handy for cross burnings,” he suggests, all wide-eyed and innocent. “That’s not cool,” shoots back the Klansman. “How come?” asks Theroux. “Tacky?”

“As a presenter, I’ve always been slightly unorthodox,” says Theroux now, talking to me from his home office in north-east London, where he’s sporting a scraggly beard, a pair of snazzy headphones and a pale blue shirt with the top button undone. “The phrase ‘gonzo’ sometimes gets used. I don’t know how appropriate that is but I’ve never been a reporter who goes and does conventional interviews with people. There’s always been a sense of tension – where I’m coming from and where they’re coming from.”

Theroux once said that when he puts himself among outrageous and exotic people, his anxieties melt away. Does he feel more anxious in day-to-day life than in dangerous situations? “Is that a quote from my book or an interview?” he asks. An interview, I think. “Ah. I’ve gone into some detail in my previous book.” He leans down, picks up a copy of Gotta Get Theroux This, and holds it up to the camera. “I’ve got a new book out in November, Theroux The Keyhole” – he dives down again, picks that one up, holds it up. For some reason, it feels like he’s doing a bit.

“The bottom line is,” he concludes when he’s finished showing me his books, “I’m an anxious person. I worry about things. I get antsy, I get nervous. I try to find ways of dissipating the nervousness. Joe Wicks workouts help. Cooking. When I’m on location doing stories, that’s another way to alleviate all those stresses and concerns. Without getting too… I’m not paying you to be a therapist… but some of my anxieties are to do with work and achieving what I need to do, not letting people down. But it’s like what they say about boxing: in the lead up to the fight, you might be nervous, but once the bell goes and you start fighting, it’s pure heat. Now we’re in it. We can… not exactly relax, but the concerns fade away and it’s showtime and you are absolutely doing it. There’s nothing more to worry about because it’s happening.”

Theroux is as warmly disarming as I expected. Antsy, too. Here to promote the gripping new four-part documentary series he’s executive-producing, The Bambers: Murder At The Farm, he’s worried that he’s “the least qualified” person to be talking about it. He worries, too, that he’s seeming too self-important; that he’s using the word “connects” too much; that he’s being “really boring”. When my foster cat bursts into the room meowing, Theroux asks if everything’s all right. Yes, sorry, it’s just the cat, I say. He is visibly relieved: “Wow, I thought it was a child.”

That he’s able to bond with his variously eccentric subjects, he says, is down to feeling like an outsider himself. Not in any literal way – the son of the American novelist and travel writer Paul Theroux, he had a privileged upbringing – but in his sense of self. He attended, but hated, the historical private school of Westminster, only feeling he’d found a “place in the world” when he went into sixth form and befriended future comedians Adam Buxton and Joe Cornish. His identity was something he struggled with into his twenties. “I was more confused,” he says now. “I was ambitious, but I wasn’t sure what I was ambitious for. I was trying to figure out where I fit in the world, and all of that led into a sense of being an outsider. I felt that licensed me to take a more adversarial attitude. That cuts both ways, though, because I identified quite strongly with people I interviewed, but I also thought it was part of what made me different.”

How do you hold onto that feeling, then, when people start putting your face on mugs, T-shirts, prayer candles, their bodies? Theroux’s fanbase, which exists mostly in the UK, is almost cult-like in its love for him. “I think that in certain respects, I still feel like an outsider,” he says, after pondering the question for a minute, “but I have enough self-awareness to recognise that, by dint of having a 25-year career in television, and being a recognisable BBC face, and by being part of a mainstream establishment media class, I am not an outsider. It would be weird to pretend otherwise.” Still, he adds, “I try to hold on to some sense of outsiderness, because I think it’s a healthy mindset”.

Then again, being a straight, white man has helped him, too. He’s gained access to people who would otherwise not have let him cross their threshold: the homophobic Westboro Baptist Church; the racist KKK; the antisemitic neo-Nazis. They trusted him because he could, conceivably, have been one of them. “Quite evidently I am the beneficiary of whatever tolerance or goodwill extends to me if I’m among racists,” he admits. It’s why in Louis and the Nazis, for which he travelled to California to meet members of the White Aryan Resistance, he decided he would refuse to say whether or not he’s Jewish. “At some point, I made a deal with myself that I wouldn’t say,” he recalls. “There were two reasons: one is a principled stand – that actually it shouldn’t be important to them whether or not I was. But also, it was out of a slightly trollish awareness that it would wind them up more. If I said I was not Jewish, which I’m not, all the conflict would go out of the encounter. And there’s an enjoyable provocation in refusing to answer the question.”

What would he have done if a member of the Westboro Baptist Church, an American hate group who picket funerals with signs saying “God hates f**s” and who have been the subject of three Theroux films, had asked if he were gay? “Depending on the context, I might not answer the question,” he says. “I don’t think the question ever came up. I think they googled me and found out I was married. But I am what I am. And what’s going on now is an awareness that to a great extent, straight white men such as myself have been monopolising the conversation a bit. There are steps that need to be taken to remedy that and bring other voices out. At the same time, I don’t think it’s the case that I can’t do my job anymore. Otherwise, I would stop doing it.”

Instead, he’s set up a production company, MindHouse, so he can produce documentaries in which he’s not on camera. One of them is The Bambers: Murder at the Farm. The series, directed by Lottie Gammon and produced by Flo Barrow, explores a gruesome mass murder that took place in an Essex farmhouse 36 years ago. The five victims were a young mother, Sheila Caffell, her six-year-old twin sons Daniel and Nicholas, and her adoptive parents, Nevill and June Bamber. At first, police ruled it a murder-suicide committed by Sheila, who had suffered from schizophrenia. Fresh evidence, though, put Sheila’s brother Jeremy Bamber in the frame. He was arrested, charged and convicted of all five murders – but maintains his innocence to this day, from his maximum-security prison cell. The Bambers: Murder at the Farm uses first-hand testimony and archive footage to re-examine the case.

I’ve seen three episodes now, and it’s certainly a gripping story, told with the right balance of intrigue and sensitivity. “I obviously feel a bit embarrassed to be speaking on behalf of the production,” says Theroux, “because I put in far fewer hours than any of the other people. But I feel very proud that I was able to collaborate with talented people.” He’s particularly proud that he recruited a female director, who gave birth six months into filming, and a female producer. “It’s been a subject of discussion for a few years: are female directors getting enough breaks?” says Theroux. “I’m giving myself a great big pat on the back, so apologies that you have to watch me do that,” he adds, “but I do feel thrilled that I made that work and we have a great series.”

When I speak to Gammon over email, she says what drew her to the case was its uniqueness. “It’s one of the worst mass killings in British history so it is rare, if not unprecedented, that the person at the heart of the case has maintained his innocence for so long,” she explains.

‘The notion of stereotypical victim behaviour is quite dangerous’

Theroux was 15 and at boarding school when the murders happened. “A friend used to get The Mirror, and the famous images of Jeremy Bamber at the funeral, his face a mask of grief, they were very powerful,” he recalls. “It was one of the landmark events of the era, for reasons that relate to family life, class, social status and the contrast between the outward trappings of a rather handsome, successful family with much more going on behind the scenes.”

With every layer the documentary peels away, the Bambers become more fascinating. Nevill was an avid collector of guns. June was a religious zealot who called her daughter the devil. Sheila would ring her father thinking she was Joan of Arc. Jeremy may or may not have dealt heroin in New Zealand. What most fascinated Theroux was the thread of mental illness running through the narrative. “Psychosis is real – violent psychosis is also real,” he says. “It’s not impossible to suppose that Sheila had a psychotic episode, or even that she did do violence to her family. But having made a film about psychosis” – in 2019, he made Mothers on the Edge, which tackled postpartum psychosis – “[I found that] the fear of doing violence to their children can be articulated by some mums, but that doesn’t mean that you’re a risk. That may be something that will always remain in the realm of the non-concrete, something you would never actually do.”

“I think the press treated mental health very differently in the 1980s and I hope Sheila’s story would have been handled more gently today,” agrees Gammon. “I think the case of a mother believed to have killed her own children would be treated as a tragedy rather than a salacious story these days – I hope so anyway. I think the fact that Sheila was a beautiful model certainly added fuel to the coverage. The papers knew they had a great photo they could run over and over.”

We glean more about the family’s backstory as the series goes on. “The circumstances of the adoption of both Sheila and Jeremy in light of June’s mental health are quite shocking,” says Gammon. “But even if Sheila hadn’t been a suspect, I think a murder like this involving a middle-class family in a quiet farmhouse would have been a front-page story. Once Bamber was in the frame, it also ran and ran because he was this ‘haughty, fine-boned youth’ – quoting [the journalist] David James Smith.”

Once he was under suspicion, Jeremy was depicted in the press as a “cold-blooded psychopath”, says Theroux. Multiple people in the documentary note that he didn’t grieve the way a “normal” person would. That rang alarm bells. “So often, we hear of false allegations being premised on a sense of what your behaviour – either as a perpetrator or a victim – is supposed to be like,” says Theroux. “‘She didn’t behave like somebody who has just been sexually assaulted.’ That’s a total misapprehension, because people behave in a variety of ways. The whole notion of stereotypical victim or perpetrator behaviour is quite dangerous.”

Theroux has spoken to many survivors of sexual assault in the past decade – as well as accused perpetrators of it. Since around 2011, his programmes have become less “puckish”, as he puts it, the subjects no longer just people with unconventional or hateful lifestyles, but those with dementia, autism, brain injuries and addiction issues.

The first time he spoke to a sexual assault survivor on camera was when he revisited the Jimmy Savile story. Theroux had first met the children’s TV presenter, who we now know was a prolific sex offender, in 2000, for the first episode of his When Louis Met… series. Savile was a childhood hero to Theroux, and they got along well – awkwardly well, in hindsight – though Theroux has bristled at the idea that he let Savile off lightly. In fact, while visiting his flat in Leeds, he brought up the rumours that Savile was a paedophile. Savile, dressed as usual in his seedy tracksuit, a cigar hanging from his mouth, casually denied them.

After he died in 2011, hundreds of women came forward accusing Savile of having sexually abused them, some when they were children. A huge investigation followed, and an “unprecedented” number of victims came forward: 450 in total. Theroux felt compelled to revisit the story in 2016, speaking to some of Savile’s victims and trying to understand how he and so many others had failed to see Savile for what he was.

“Growing up in the 1980s,” says Theroux now, “the idea that Jimmy Savile might be a paedophile or a necrophile, it occupied the same drawer as the idea that a pop star had his stomach pumped and they found 10 pints of semen, or that a Hollywood actor had a rodent removed from his rectum. Both of them are rumours that are not true. That Jimmy Savile goes around fiddling with kids – I thought that was in the same category. The only thing that felt odd later on was the idea that everyone in the playgrounds in the 1980s heard that rumour, so I can only imagine everyone involved in the media would have heard a rumour that there was something dodgy about Jimmy Savile.”

When I was growing up, the idea that Jimmy Savile was a paedophile was a playground rumour

He’s not being flippant, though. “That’s quite obviously of a different order of seriousness to someone in a hiring and firing position being told that there’s a complaint about Jimmy Savile on the set of Top of the Pops. I’m not in any way trying to equate those two. I think one of the things we’ve suffered is this elision of different magnitudes of information, and how exposed you were, how much you knew. You only have to read the Janet Smith enquiry to realise that complaints were made and disregarded.” That 2016 review, commissioned by the BBC itself, found that Savile had sexually abused or raped people at “virtually every one of the BBC premises at which he worked”, and that some BBC staff members knew of complaints against Savile but didn’t pass them on to senior management thanks to a “culture of not complaining”.

“Hopefully, that’s a lesson we learn,” continues Theroux, “that you have to safeguard vulnerable people, and at every stage you have to make sure that people in positions of authority are being monitored.”

“Trollish” though Theroux may be with those who deserve it, the Savile documentary showed him as a sensitive, empathetic interviewer when it comes to speaking to victims and survivors. At the start of this year, for an episode of his lockdown podcast Grounded, he spoke to FKA twigs. They’d already done one interview in late 2020, when the musician had chatted about her love of Adam Ant, growing up in Gloucestershire, and her relationship with the music industry. Theroux had asked whether her record company was happy with her sales figures, “and she said for the first time in her life that made her feel like a failure”, he recalls now. It was his favourite part of the interview. “Her willingness to call me out and us work through that in a friendly way, that felt very real and weirdly enjoyable. There’s a fine line between good awkwardness and bad awkwardness.”

Months later, though, in December 2020, twigs filed a lawsuit against her ex-boyfriend, Shia LaBeouf, accusing him of sexual battery, assault and emotional distress (he has denied allegations of physical and emotional abuse). The episode of Grounded had not yet been released. “I thought, ‘Well, I don’t want to crassly swoop in and say let’s definitely talk about this,’” says Theroux. “Not to say it didn’t cross my mind, but I thought it was really her call.” Then her manager got in touch. He asked Theroux if he’d be happy to talk to twigs again. “I said absolutely. It took the pressure off me somewhat. In that situation, the premise of the follow-up conversation was that she’d reached out to me because she wanted to talk about something.”

It’s an extraordinary conversation, raw and honest, twigs speaking with a hard-fought resolve. As well as detailing the alleged abuse, which left her with PTSD, she takes pains to highlight red flags for abusive relationships: “the grooming, the pushing of your emotional and spiritual boundaries ... I was told that I knew what he was like and if I loved him, I wouldn’t look men in the eye,” she says. “That was my reality for a good four months.”

“Conversations with people who have survived something dreadful are more difficult to navigate,” says Theroux. “There’s more risk involved. I suppose it’s very human – a feeling of not wanting to get it wrong, of wanting to talk in a way that feels supportive or empathetic. But you’re a journalist, you’re not a therapist. You’re trying to figure out what happened and how it happened. There are risks of appearing to be unsupportive, or indeed being overly, uncritically accepting. Nobody has a monopoly on the absolute truth – that way madness lies. You still have to do your job.”

Then again, Theroux would like to start doing his job a little bit less. “I would like to slow down a bit,” he says with a sigh. “I’m 51 and I’m increasingly aware that I’m starting to go bald. Some people retire in their fifties. Now not that, but I would like to have a hobby or something.” He gazes into the distance, trying to pick a hobby on the spot. “Playing tennis?” he suggests. “Other people do stuff. Maybe I should be able to do stuff.” There’s always another Joe Wicks workout. If he’s willing to brave the garden again.

The Bambers: Murder at The Farm premieres on Sky Crime and streaming service NOW on Sunday 26 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks