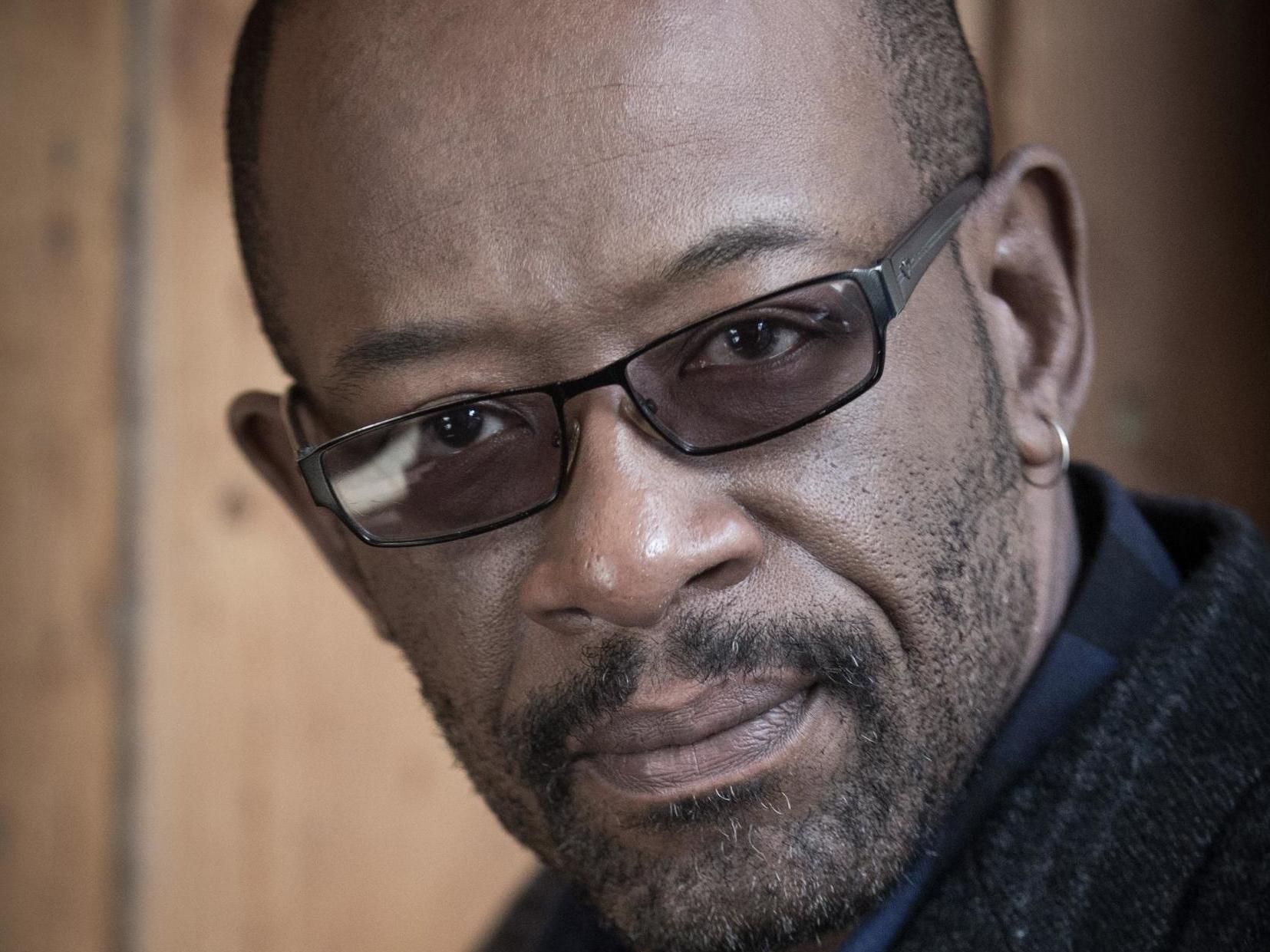

Lennie James: ‘The Tories have been dishonest about coronavirus – it’s a dangerous game’

The creator and star of ‘Save Me Too’ talks to Ellie Harrison about government failings, growing up without his father, and why he’s not ready to write about racism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lennie James was on a plane when his life changed forever. It was 1990, and the actor – aged 24 at the time – was flying home from Dominica, where he’d been filming a miniseries called The Orchid House.

“Dominica is historically one of the blackest islands in the West Indies,” the 54-year-old says. “It has very little colonialism and white presence because it’s a volcanic island. When I was there, the people driving the taxis, managing the hotel, running the country, farming the land, working in the banks, writing the newspapers – everybody looked like me. Everybody was black.”

On the flight back to London, when the pilot announced the plane had left West Indian airspace, James broke down. “I cried like I’d never cried before in my life,” he says. “I cried and cried. My wife was really worried, asking what was the matter… I suddenly thought, ‘I’m back in the UK,’ and I swear to god I could physically feel my body tensing. It felt like I was putting my armour back on – what I needed to survive as an ‘ethnic minority’, as they called us then.”

That armour, he says, “was physical and emotional, and because I had been released from it for eight weeks, it was only putting it back on that I was aware of just how heavy it was. It was the first time I really realised what I had to do in order to live as a black man at home in the UK.”

James wants to explore that profound realisation in his work. Known for playing the first bent copper in Line of Duty and devoted father Morgan in The Walking Dead, he’s got two writing credits under his belt – his Bafta-nominated 2000 TV film Storm Damage, about a teacher who returns to his London foster home, and Save Me, the second series of which (Save Me Too) he’s on Skype to discuss – but he’s yet to delve into the issue of race. “I haven’t had an idea yet that allows me to explore the damage racism does, how far deep down it goes,” says James. “How it makes you conscious of how you walk down the road and affects the decisions and the compromises you make. How much effort you put into f***ing explaining racism to white people and making it alright for them. How f***ing tiring it is.

James is a galvanising conversationalist. He speaks with such eloquence and intensity that even over a dodgy internet connection it’s impossible not to be moved by his words. “A lot of the time, racism is still seen through the lens of the white community,” he continues, “and I haven’t found a way that incorporates black people speaking to each other about what it is. People try to express it now in terms of white privilege but it isn’t just about advantage, it’s about what it costs. I don’t see that talked about nearly enough.”

James was raised in London by his mother, who died following a long illness when he was 10 years old. She was part of the Windrush generation. “When she showed up [in England] there were literally signs on the door saying, ‘No blacks, no Irish, no dogs,’” he says. “My mum said to us, ‘You’re going to come across a lot of people who don’t want you here. This is how you navigate it: you make sure you’re so good they can’t shut you out.’ That’s what we had to strive for. For most parents, that was about education. You get an A at school, it doesn’t matter if you’re black or white – you got an A. Because of this pressure, I was constantly aware of the shape I cut in the world. Most of my white friends when I was growing up, they just weren’t, and they didn’t have to be.”

After James’s mother died, he and his brother lived in a children’s home and were later fostered. He has no memory of his father. “I had uncles and other people who’ve filled in as father figures,” he says. “I don’t wish any ill on my dad but I never missed him. Perhaps that’s because of the good job my mother did. When I speak to my kids about it, they just can’t understand that. It’s probably because they know what they’d be missing. It’s a bit like when people say they grew up not knowing they were poor – they didn’t know what they didn’t have.”

Fatherhood is the central theme of Save Me Too, James’s exhilarating, gritty redemption drama that finishes on Sky Atlantic next week. He wrote the show and stars in it as Nelly Rowe, a south London geezer searching for his estranged daughter after she’s kidnapped and sold into a sex-trafficking ring. He’s assembled a terrific cast for the series, with Lesley Manville joining Stephen Graham, Suranne Jones and Jason Flemyng for the new season.

It’s set on an estate in Deptford, and James’s attention to detail – kids riding around on supermarket trolleys; the local pub’s eccentric collection of regulars; Nelly’s Jack-the-lad ringtone – has marked him out as one of the country’s best chroniclers of working class life. Like stalwarts of the genre Shane Meadows and Ken Loach, James strives to show “how these people love, how they laugh, how they raise their kids and how they live”, rather than focusing on what he calls “issues”: unemployment, social status, drugs and gangs. Loach’s son Jim, as it happens, directs Save Me Too.

The drama is a searing study of grief. The events of series two take place 17 months after the disappearance of Nelly’s daughter Jody, when he’s facing up to the fact he might never find her. He screams at friends in the pub who discuss lighting candles for Jody, furious at the implication that she’s dead. In one of the drama’s most heart-rending scenes, Jody’s mother, Claire (a brilliant, angst-ridden Suranne Jones), confides to a friend: “It’s like I tripped a year and a half ago. That’s what it felt like when she went. Like I tripped and fell and I haven’t stopped falling, hurtling, without ever landing. I just want it to stop. I just want to hit the f***ing ground.”

James, who has three daughters and describes himself as a “very involved” parent, says it’s his experience of fatherhood that enabled him to draw Nelly and Claire’s despair so convincingly. Losing a daughter, he says, “is not something I want to spend a huge amount of my brain space thinking about, but it’s not hard to get into Nelly’s head”.

He’s hoping to write a third series of the show, and Sky is interested, but for now he is holed up in Austin, Texas, for lockdown. It’s where he would have been filming Fear the Walking Dead, had it not been for the global pandemic. He has lived in Los Angeles since the mid-2000s, witnessing the sense of hope that swept through the country when Obama became its first black president, and later watching on in horror as he was succeeded by Trump.

He is anxious about the prejudice his children, who have grown up in America, face. “I don’t think racism is any different here to in the UK,” he says, “I just think it has a different accent and a different history. I do worry about it, yes. I was from a generation of firsts. For everything I wanted to do, there were either very few or no people that looked like me doing it. My kids’ generation had Obama, had people on the moon, scientists, doctors, everything. Things were supposed to be better, but I’m not sure that they are.

“We went from Obama to Trump. One minute everyone was flippantly saying that racism was over, the next minute there’s a massive rise in far-right extremists and white supremacists. So, am I worried? Yes, I’m worried. Who wouldn’t be? It’s not a time to pat ourselves on the back and say we got over racism.”

James is appalled by Trump’s handling of the coronavirus crisis, especially the president’s recent musings about whether disinfectants can be injected into the body to treat Covid-19. “He is arguably the most powerful man in the world,” says James. “The level of irresponsibility is staggering – that could cost people their lives and he knows it. He knows who listens to him, who heeds him.”

He laments that medical experts around Trump appear “too frightened” to contradict his “utterly idiotic” remarks. “Everybody joins the dance,” says James. “No one is saying, ‘By the way, the emperor has no clothes on. He’s naked and this is bulls***.’ No one’s doing it.”

James has been “keeping tabs” on the UK government’s response to the pandemic, too. “The Tories have been less than honest in their statements about it,” he says, “but the voices of the opposition and experts in the UK have been loud and immediate and that’s a very good thing. The hardest thing is when governments are dishonest. I find the choice to say something you know not to be true about numbers and testing to be a dangerous and irresponsible game. It gives people a false sense of security and influences their behaviour.

“Boris seems to be singing a slightly different tune now that he’s gone through it and it’s directly affected him, but I don’t understand why people who choose to be politicians and represent us are people who can’t empathise with others, until something happens to them.”

He sighs. “I don’t know why they’re doing that job. I find it surreal.”

‘Save Me Too’ concludes on Sky Atlantic on Wednesday at 9pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments