Leaving Neverland director Dan Reed: ‘We needed to establish, in the most graphic terms, what Michael Jackson was doing with little children’

As the controversial documentary about the King of Pop is released in the UK, director Dan Reed speaks to Alexandra Pollard about the reaction from Jackson’s fans and the estate, and the aftermath for his alleged victims

“Michael Jackson was one of the kindest, most gentle people I’ve ever known,” says Wade Robson in the forthcoming Channel 4/HBO documentary Leaving Neverland. “And he also sexually abused me. For seven years.”

So harrowing and human is Dan Reed’s new film – in which James Safechuck and Wade Robson detail the childhood abuse they say they experienced at the hands of Michael Jackson – that it’s hard to imagine the King of Pop’s legacy ever being the same again.

Clearly, the Jackson estate knows that. In a 10-page open letter to HBO, its lawyers described the documentary as “disgraceful”, “sensationalist” and “one-sided”. “The estate was never contacted,” they complained, “to provide the estate’s views on, and responses to, the absolutely false claims that are the subject matter of the programme.” Their attempts to halt the film failed, though – it’ll air on Channel 4 over two consecutive nights next week.

Reed – who has been making documentaries for more than 20 years, on subjects such as terrorism, Christianity, 9/11, sex work and natural disasters – was disgusted by the letter. “This is about children who were molested,” he tells me. “What would the Jackson estate have to say about what happened in a hotel room in Paris, in 1988, between James and Jackson? Nothing. They weren’t there.”

As for the claims that the production is a “pathetic attempt to cash in on Michael Jackson”, Reed says: “Of course it’s all about money. It’s about the estate’s money. It made $400m last year [and] is trying to protect its main asset.

“I’m not making any allegations, but I think the question remains: how much did the family know?” he continues. “When did they know it? It’s clear that a lot of people in the Jackson household saw things. On the record, they testified to that. [They] gave evidence in court. But the only noise I’m hearing from the Jackson camp is the estate hurling abuse at children who were raped by Michael Jackson. I think that’s shameful.” The estate is now suing HBO for $100m.

Reed says he approached Leaving Neverland with “all the scepticism and rigour that I would approach a story about a terrorist attack”. He went deep into the archives of various criminal investigations, interviewed detectives, and read files and statements, “a lot of which directly corroborated Wade and James’s story. I didn’t include that material in the film, because I felt the family accounts had a power all of their own.”

In Leaving Neverland, Reed gives space solely to Robson, Safechuck and their families. Over the course of three hours and 10 minutes, he lets them tell their story in their own time, and in as much detail as they need.

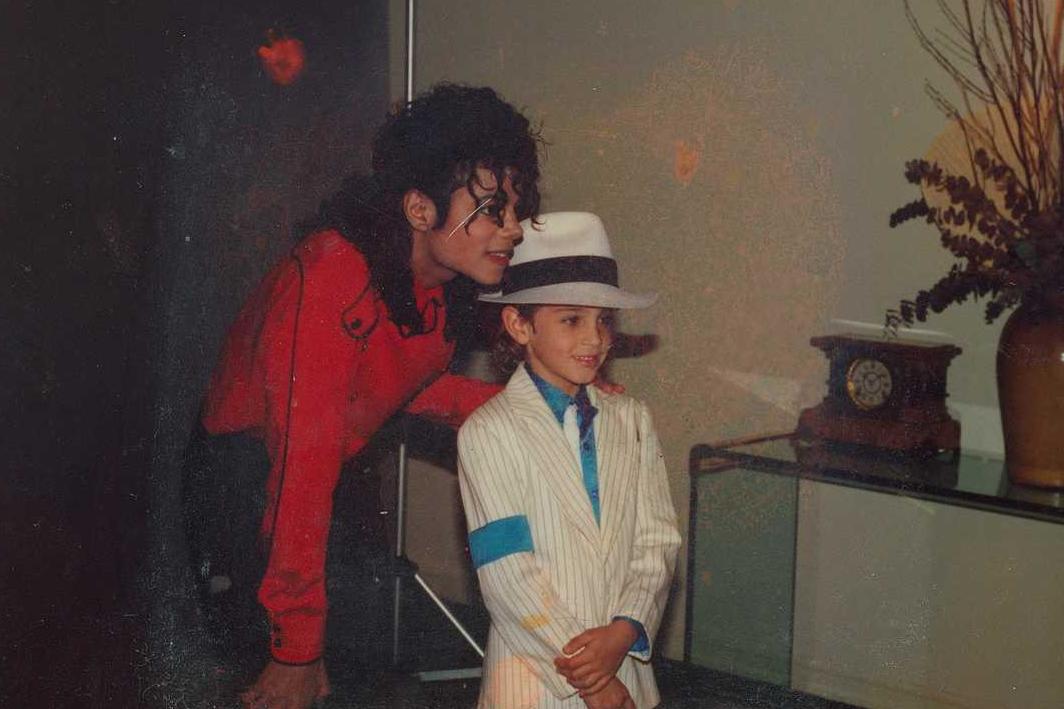

Wade Robson first met Jackson when he was five years old. He was obsessed with the pop star, and won a dance competition at a local mall in his Australian hometown. First prize was to meet Michael Jackson, but Robson was so talented that he ended up dancing onstage with him. Two years later, thanks to a few strategic calls from his mother Joy – a self-confessed “stage mom” – Robson was reunited with Jackson at the singer’s famous Neverland Ranch. That’s when he says the abuse began – abuse he recounts in graphic detail.

Reed had no qualms about including these details in the film. “For such a long time,” he says, “Jackson hid in plain sight, saying that his relationships with children were innocent, that it was cuddles at bedtime – an innocent slumber party. We needed to establish, in the most graphic terms, that what Jackson was doing with little children was sex. It was full-on sex. It wasn’t slightly inappropriate touching, or a kiss and a cuddle that went a bit too far. It was deliberate, regular sex. That’s why we needed these very graphic descriptions, to leave people in no doubt.”

Safechuck was 10 when he was first groomed by Jackson, after appearing alongside him in a Pepsi advert. Early in their “friendship”, the singer gave Safechuck the red jacket from his “Thriller” video and hundreds of dollars. Then he invited him to join him on tour for the summer. “In Paris, Michael introduced me to masturbation,” says Safechuck, “and that’s how it started. The tour was the start of this sexual couple relationship.” He opens a wooden box and shows the cameras a ring from a mock wedding between the pair. It no longer fits on his adult-sized finger. “Every night, there was abuse,” he says, “while my mother was next door.”

The questionable actions of Safechuck and Robson’s mothers loom large in Leaving Neverland. Time and again, they allowed their sons to stay the night with Jackson unaccompanied. The second time they met the singer, Joy Robson and her husband left their son for five days straight, while they visited the Grand Canyon. Both mothers are interviewed throughout, and willingly admit the devastating consequence of their decisions. “I had one job,” says Stephanie Safechuck, “and I f***ed it up”.

Watching the documentary, you’ll find it hard not to feel anger that Jackson repeatedly escaped justice before his death in 2009 – each time managing, in the words of Channel 4’s director of programming Ian Katz, to “effectively buy his way out of trouble”.

In 1993, a 13-year-old boy called Jordan Chandler accused him of sexual abuse. The case was settled out of court for $22m. “We will land on you like a ton of bricks,” his lawyer yelled in a frighteningly hostile statement, “if you do anything to besmirch this man’s reputation.” Ten years later, Jackson was in trouble once again, this time charged with molesting 13-year-old Gavin Arvizo. After a trial spanning 18 months – during which Robson, then 21, appeared as a witness for the defence – he was found not guilty. “I’m absolutely convinced that Gavin was telling the truth,” says Reed, “and it was just a sorry, terrible outcome.”

“I wish I was at a place where I could be a comrade for him,” says Robson in Leaving Neverland – but at the time, he and Safechuck were still denying that Jackson had ever laid a finger on them. They had both grown up and got married before they told a soul what had happened to them, after many years of deeply suppressed trauma. “They say time heals all wounds, but it doesn’t heal this one,” says Safechuck. “It just gets worse.”

It’s not unusual, says Reed, that Robson and Safechuck not only denied Jackson had abused them, but actively loved and supported him well beyond childhood. “When children are sexually abused they can form a deep attachment to the abuser,” he explains. “They often don’t tell the parents, and the abuse often only comes to light when the victims are in their thirties and have their own families.”

As Leaving Neverland’s release approaches, there is one question Reed has been asked constantly: am I going to have to stop listening to his music? Jackson is, after all, a phenomenon. He is the third-best-selling music artist of all time, won 13 Grammys, had 13 US number ones, and his 1982 album Thriller sold more copies than any other album in the world.

Reed doesn’t particularly care. “That’s not the point. I don’t care about toppling Michael Jackson. The question we should be asking is, ‘Should I trust my children to this stranger?’ The question that child sexual abuse victims should be asking is, ‘Is this the time for me to come out and tell my story to those around me? Can I tell my mum?’ I don’t care whether people listen to Michael Jackson’s music or not. It’s about the man and not the music. But the man appears as a much different figure after watching the film. He hurt a lot of people. He was cruel. He was vicious. How you reconcile that with the music is a private matter.”

If Reed hopes to achieve anything from Leaving Neverland, it’s that “it updates our understanding of child sexual abuse. I’m not saying anything new in the film, but I hope we’re saying it to a much wider audience. If victims of child sexual abuse watch it, and they haven’t spoken out, they can take some comfort in the fact that Wade and James are bravely speaking out against a powerful abuser.”

That’s Robson’s hope, too. “I want them to be able to speak the truth,” he says of other victims, of Jackson or anyone else, “as loud as I had to speak the lie for so long.”

Leaving Neverland: Michael Jackson and Me will air on Channel 4 on Wednesday 6 and Thursday 7 March

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks