John Hamm on Baby Driver, rehab and life after Mad Men

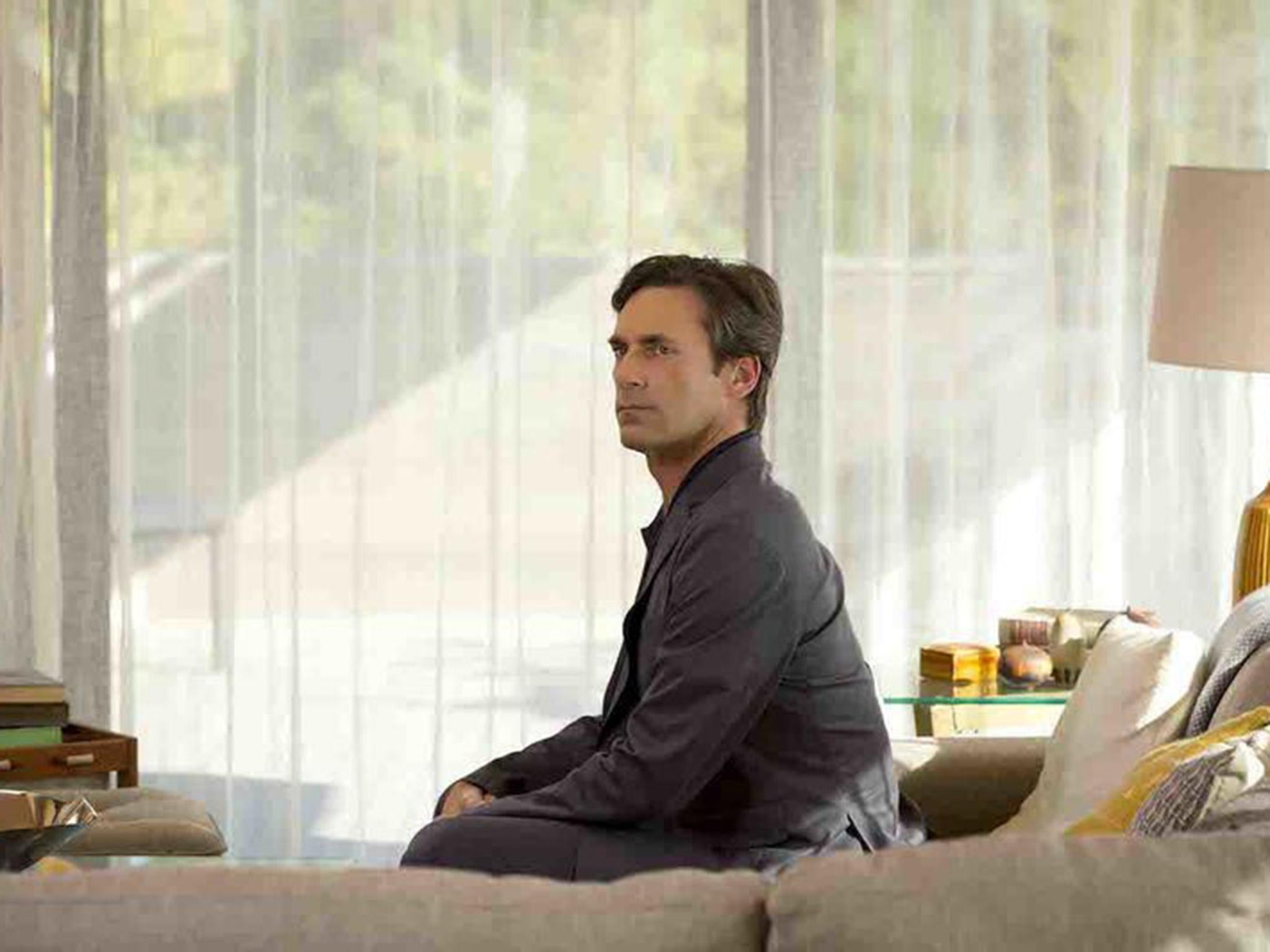

More than two years after Mad Men, the man who was Don Draper, has gone through changes in his personal life while trying to get a movie career going

I had only two or three questions for Jon Hamm. I wanted to know if fame had rattled him. I wanted to know if, more than two years after the Mad Men finale, he had plotted out a second act worthy of his talent. I wanted to know if he still wanted to be a star.

We were supposed to meet at the edge of Central Park at 11am and take a walk. Then came the rain. So we switch the location to Pearl Studios, a suite of rehearsal rooms in Midtown where actors and dancers audition for Broadway shows, touring companies and cruise-ship work.

I text to say I would pick up coffee. How did he like his? “Black!” he texts back.

At Cafe Grumpy on West 39th Street I pick up two black coffees, extra-large. They are lawsuit-hot. The walk in the rain to Pearl Studios seems long. A few minutes past 11 comes another text from Hamm, whose politeness may owe something to his Missouri upbringing: “I’m one very congested crosstown block away. Sorry!!”

If you still picture Don Draper when you think of Hamm, it may strike you as odd to see him emerge from a Nissan NV200 yellow cab, which has a boxy look very much at odds with the elegant midcentury universe of Mad Men.

He is wearing a white linen dress shirt with the two top buttons undone, khakis and white sneakers with black laces. A Timex Blackjack watch and a St Louis Cardinals cap with a vintage logo completed the look. He accepts his coffee with a thank you and takes my hand in a meaty paw.

Since completing his work on the show that made him famous, Hamm has gone through changes in his personal life while trying to get a movie career going. In 2015, he spent a month in treatment for alcohol addiction at a rehab facility. Some months after that, he and his partner of 18 years, the writer, director and actor Jennifer Westfeldt, announced that they had broken up.

The movies came out one after another: Million-Dollar Arm, in which Hamm plays a sports agent who grows a heart, thanks to a saucy medical resident (Lake Bell); Keeping Up With the Joneses, an action comedy starring Zach Galifianakis in which he and a pre-Wonder Woman Gal Gadot portray spies; and Baby Driver, a crime fantasy in which he appears as a somewhat deranged third banana.

“I always say I make the movies where people go, ‘Hey, I never saw it, but when I finally did, I really liked it,’” Hamm says. “People saw Baby Driver, though. I was pleased with that.”

His most recent film, the melancholy Marjorie Prime, is a well-reviewed adaptation of a Jordan Harrison play directed by Michael Almereyda that includes a much-buzzed-about performance by Lois Smith.

“I watched Michael Almereyda’s movies and I read the script and I thought: I like his movies, I like this script, let’s put this chocolate and peanut butter together and see if we can get a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup,” Hamm says. “I didn’t know what the movie would end up being, and then I watched it right before Sundance and I was moved.

I mentioned that the final scene, with its focus on a character’s relationship with a dog, is affecting without being sentimental.

“Don’t even talk to me,” Hamm says. “I just lost my dog yesterday.”

He was talking about Cora, a shepherd mix he had gotten with Westfeldt in the early years of their relationship.

“Cora was the best,” he says. “I was scheduled to fly in at 8 o’clock in the morning, and she passed away right before I got there. It’s been a real hard 24 hours for both me and Jen.” A long pause. “She was 17. She brought a lot of love and a lot of good times to me and other people and Jen, and she’ll always have a real sweet place in my heart. I could go on for three hours about Cora, and I won’t, because I’ll just be a mess.”

He takes a sip. “What is this coffee, Grumpy? That’s the one from Girls, right?” he said. He studies the frowny-face logo on the cardboard cup. “I’m a big dog fan. They’re the best. They make life better, although they’re hard to deal with. But complications in life are actually what make it fun. If it wasn’t raining today, you know, whatever, I’m glad it rained. And the more people you meet – I’ve had the incredible fortune to meet amazing people, sometimes out of dumb luck, but mostly out of being famous for 10 minutes on a TV show. I could listen to Lorne Michaels tell stories for a hundred years. And he wouldn’t run out. Mike Nichols. Diane Sawyer. Marlo Thomas. Patti LuPone. Meryl Streep. And then friends of mine, also.”

In this category he mentions Jon Stewart and Hannibal Buress, whom he had seen perform the night before as part of Dave Chappelle’s run of shows at Radio City Music Hall. He also notes his Mad Men colleagues Elisabeth Moss (“Lizzie”) and John Slattery (“Slatty”), the directors Greg Mottola and Edgar Wright, and Rosamund Pike (“Roz”), his co-star in High Wire Act, a yet-to-be-released thriller written by Tony Gilroy.

“Like, how are we friends?” he says. “How did I get here? I’m from Nowheresville, Missouri. But it was instilled in me from an early age: Why not you? Just because you’re x-y-z from Nowheresville doesn’t mean you’re nothing.”

Show business is filled with good-looking people. The ones who make a mark have emotional depth. In Hamm’s case, the mystery, the charisma, the sense he gives audiences that there is more to him than just a strong jaw probably has something to do with his childhood.

His parents divorced when he was two. He lived with his mother in an apartment complex after that, and she died when he was 10. His father, a gregarious man who was in the family trucking business for most of his working life, sometimes parked the young Hamm in front of Saturday Night Live at parties. The boy ended up spending a lot of time at the houses of two friends. The mothers looked out for him through his time in high school, where he was the rare teenager who excelled at both sports and theatre (he played Judas in Godspell), and again after his father died when he was 20.

“When you’re a kid, you’re just not equipped to deal with some of the stuff that life brings you,” he says. “It’s why you have parents. And then, when you don’t, there better be somebody who fills in that gap, or you’re going to be rudderless for a while.”

I bring up the rehab stint. Did it give him a chance to reset himself?

He replies in almost a whisper: “Recalibrate. Re-evaluate. Just sort of re-establish where you are. You’re coming off of this Tilt-a-Whirl that’s going 9,000 miles an hour, and so many things have come unfixed. If you think about navigation, you’re trying to stare at a fixed point. When you navigate to something that’s whirling, it’s difficult. It’s all a learning experience. It’s all about growing older and getting better at living. And I hope I did.”

He gets up and took a walk around the room.

“I’ve been really breaking down this year. At 46, for whatever reason, this is the year my body fell apart.” He laughs. “I play baseball, softball, tennis. So these joints take a lot of stress and strain. My eyes are bad. I tore a ligament in my elbow. I’m just like, ‘What happened?’”

He has not been pleased with his recent performances in the wood-bat league that he is part of, in Beverly Hills, California.

“I’ve never been the worst person on the team,” he says. “Ever. And I am now. I need to get in shape. I need to rehab my elbow. It’s time to get it going. And I feel that’s kind of the MO for my head, too. And my career. Let’s improve. Let’s get better.”

He sits back down. The talk turns to Donald J Trump, whom he saw, briefly, at a Saturday Night Live party in Midtown after the episode hosted by Trump during the presidential campaign.

“He was with Bill O’Reilly,” Hamm says. “They’re both tall dudes. And I’m a tall dude. And they both do that tall-dude thing, which is try to intimidate you. And it doesn’t work on me. I’m like, ‘I’m as alpha as you. Let’s go. You’re not going to chest-bump me.’ It was a very weird night. It was the shortest I’ve ever stayed at an S.N.L. after-party.”

He says he has high hopes for the success of High Wire Act, although he describes it as “the kind of movie they don’t really make anymore, because it’s not based on a comic book or a theme-park ride”.

Even Michael Clayton, a 2007 film written by the same screenwriter, Gilroy, is not the kind of thing that gets made much anymore. “I remember walking out of Michael Clayton and being like: ‘I want to be in that movie,’” Hamm says.

It may be a good sign that he met with Gilroy to discuss the script at Cafe Luxembourg, the same Upper West Side restaurant where Matthew Weiner, the creator of Mad Men, took Hamm for a celebratory dinner after he got the part of Don Draper.

Does he still feel as driven as he was back then?

“If anything, even more so,” he says.

Before we leave the room, he says, “I hope I wasn’t too melancholy or sad,” and shows me a picture on his phone: Cora. “She was a good one,” he says. “She was a real good one.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks