Howard Smith: The counter-cultural correspondent's interviews from Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda to Raquel Welch

The late producer and journalist interviewed the key figures in American counter-culture on his New York radio show

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In late-Sixties America, the counter-culture was in ferment and revolution was in the air. Meanwhile, on his New York radio show, the late Howard smith was interviewing the prime movers for change (or not, in the case of Raquel Welch).

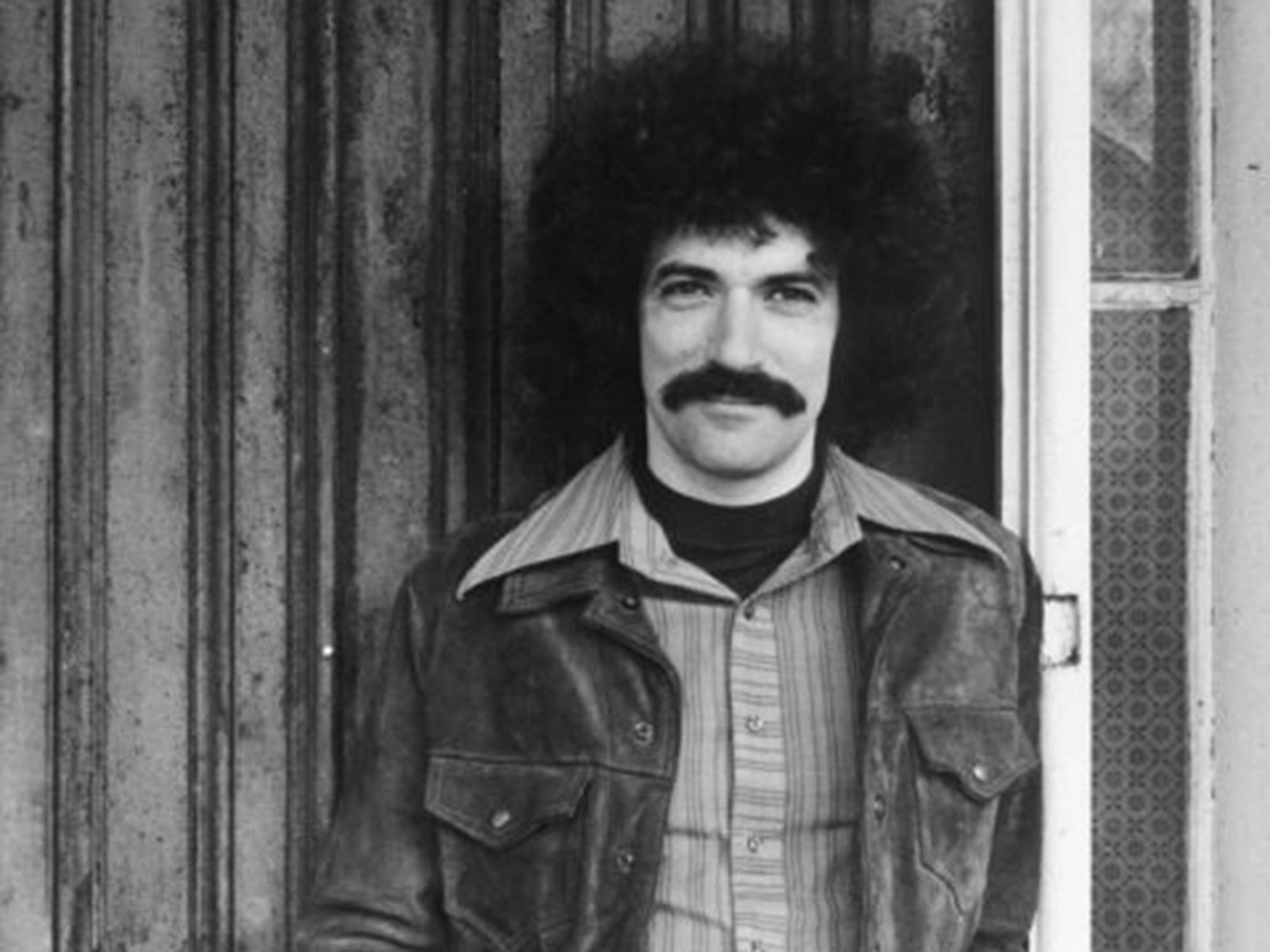

Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda, June 1969

The co-stars of ‘Easy Rider’ are giving their first American interview about the film. In a few weeks it will open across the country and instantly become a classic

SMITH: You’ve taken a very pessimistic view in the movie. Is the country in that bad a shape, you think?

FONDA: Yes. Do you think it isn’t? We have fantastic things happenin’ here, too, at the same time. Probably this is one of the freest countries I know. Maybe Sweden and this country, but –

HOPPER: The herd’s uptight.

FONDA: The big herd is uptight. I think we reflect it honestly, not only this southern part of America, but the northern part of America. I also think that we photographed America beautifully, because we happen to think that as a country, not as a political entity, it’s a beautiful place. No, seriously. You guys here in New York, all you see is these buildings and the movies that we send in to you. You know what I’m saying –

HOPPER: We wanted to make a movie about what was going on at this moment, and the experience of travelling across country with long hair. You realise pretty soon that it doesn’t have to do with whether your skin’s black or whether it’s brown or whether you have dark eyes or blue eyes or blonde hair or whatever. Anything that’s different from that herd that keeps talking about themselves as “free individuals”.

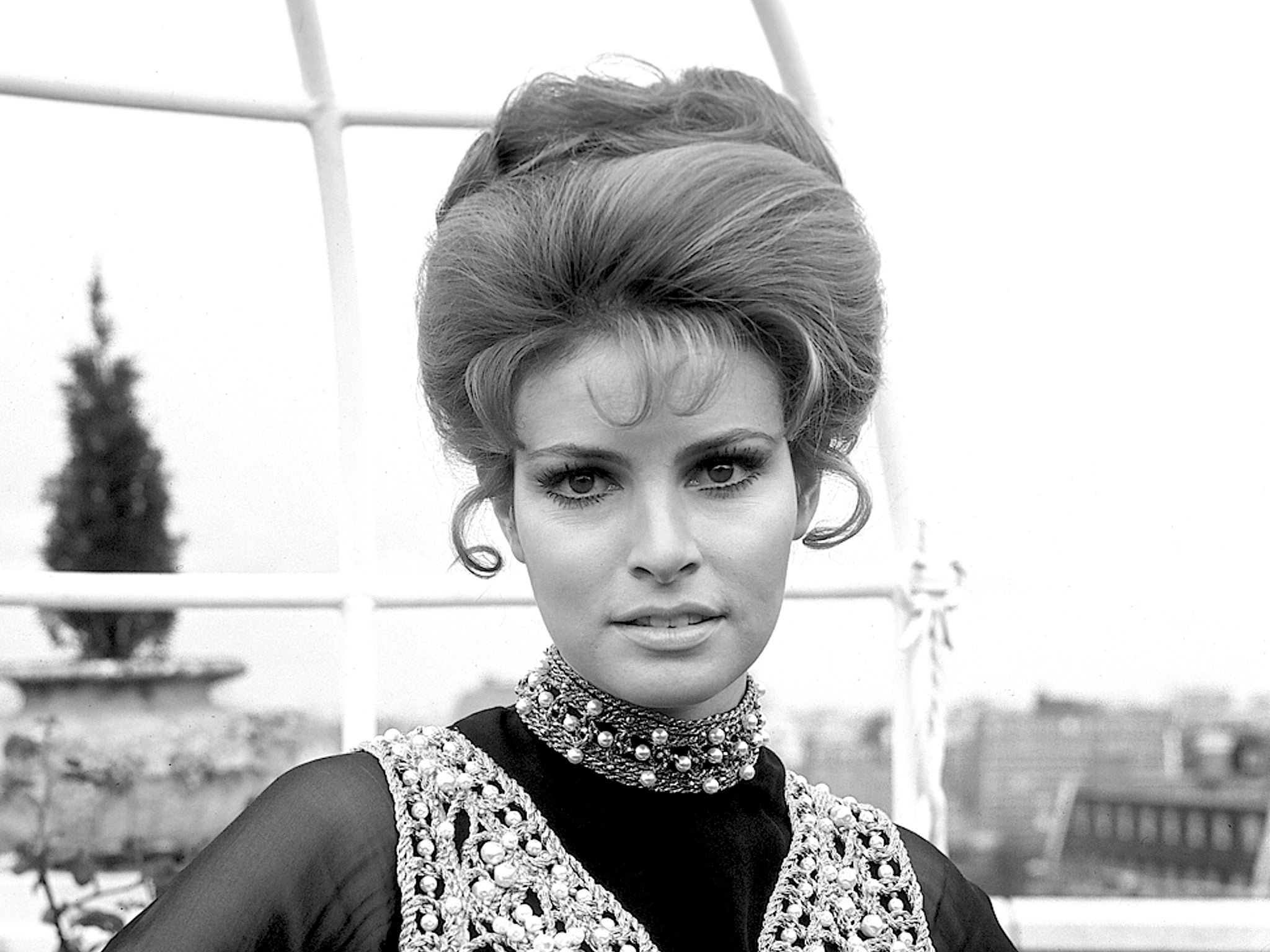

Raquel Welch, October 1969

The screen siren is playing the title role in the film “Myra Breckenridge”, an adaptation of Gore Vidal’s bestseller about a transgender person’s escapades in Hollywood. It will open next June with an X rating and be an infamous flop. Vidal will call it “the second worst film” he has ever seen

SMITH: Are you familiar with the women’s liberation movements that’ve started up?

WELCH: What, d’you mean Scum? It’s right on the tip of my tongue at every moment.

SMITH: That was just one of ’em, but it’s, like, woman power.

WELCH: I think it’s diabolical. I think it’s lunatics, really. The Scum thing I read about in Time or Newsweek, about the “Society for Cutting Up Men” – women triumph and supreme over all, and let’s get rid o’ men as a species altogether. Well, it’s just sick, isn’t it?

SMITH: That’s the extreme. More about women joining together, like where they demonstrated against the Miss America competition...

WELCH: Oh, lovely, that sounds fun. Why did they demonstrate?

SMITH: Against valuing women for the wrong reasons.

WELCH: Well, I think that women should be decorative. Don’t you?

SMITH: That’s exactly what they’re against.

WELCH: I don’t think that they’re right. It doesn’t necessarily negate other aspects of being a woman, but I do think that women should be decorative – however they go about it… As far as I’ve been alive, women have always been more or less the symbol of sexuality rather than the male. We don’t see the naked male body, do we, as the symbol of sex? We see the naked female body. I think that’s a rather nice simile, women and sex.

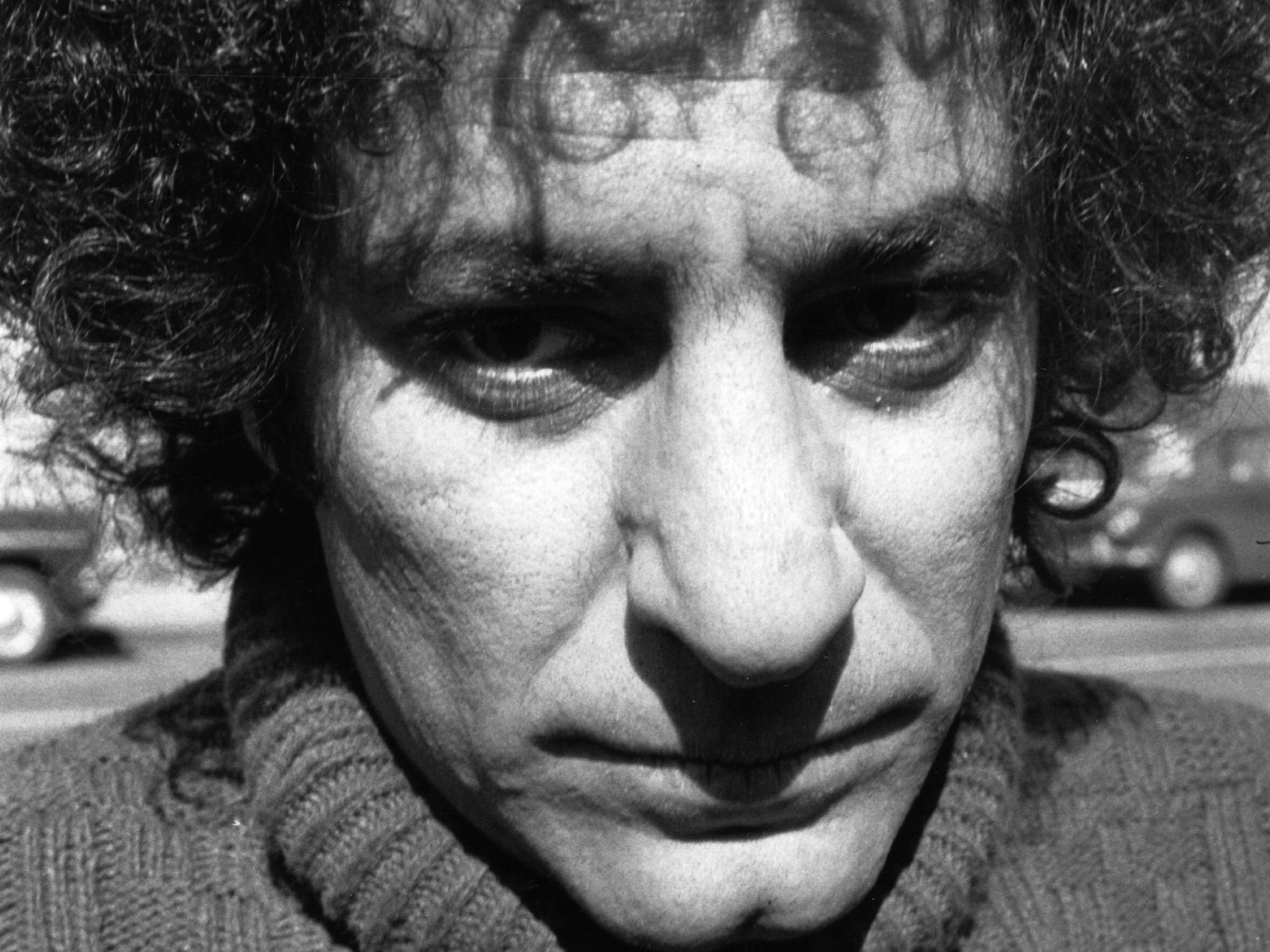

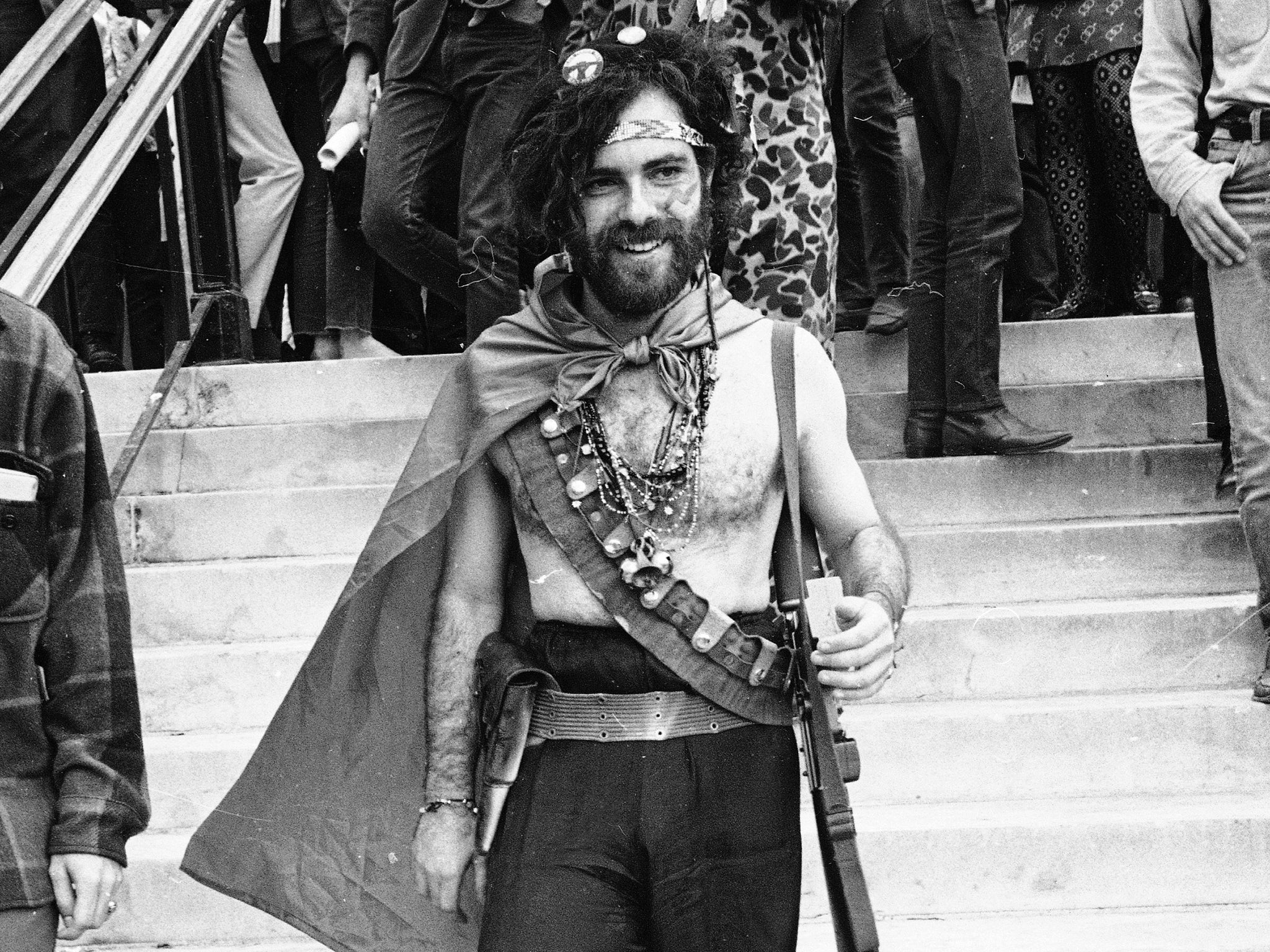

Abbie Hoffman, June 1970

Four months ago, the co-founder of the revolutionary Youth International Party (the Yippies) was sentenced to five years in prison for his involvement in organising and leading the demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. He’s due to begin serving his sentence this autumn

SMITH: What are the books that you have to do in this month?

HOFFMAN: One’s about the trial. It’s called Offence of America and [it’s] mostly my testimony, edited, and thoughts about the trial. The other one is called Steal This Book; it’s [about] how to live free and conduct guerrilla warfare in America.

SMITH: You mean literally how? With weapons and bombs and the whole thing?

HOFFMAN: Yeah, what different kinds of weapons to use, how to build an underground. I’ve done a lotta research about how, during the Second World War, undergrounds were built: how the French built their underground, how the Algerians built theirs. I mean methods of communication. There is an active underground in this country –

SMITH: In those countries there was an occupying force.

HOFFMAN: Well, we have that... There’s a very real war goin’ on in America – and a violent war. The Yippies are part of that struggle. It’s a little different than when we went to Chicago two years ago: I’m now a convicted felon, five years in prison; in September, I have to cop a plea for at least nine months –

SMITH: Really? Why?

HOFFMAN: It’s all sorta Catch-22, the law. I think it’s because I beat up three policemen while I was handcuffed with leg irons on me, which is a neat trick… I think it’s a different empire in which we find ourselves in 1970 than we did during the 1960s. Brothers and sisters of mine are being killed, and it’s not just in body counts, “four dead in Kent”, “six dead in Augusta”, “two dead in Jackson State”: they’re people like Terry [Robbins] and Diana [Oughton] and Fred [Hampton]; people that I’ve joked with, argued with, and turned on with, and it’s personal. The revolution is personal, and the deaths are personal, and the stakes are high.

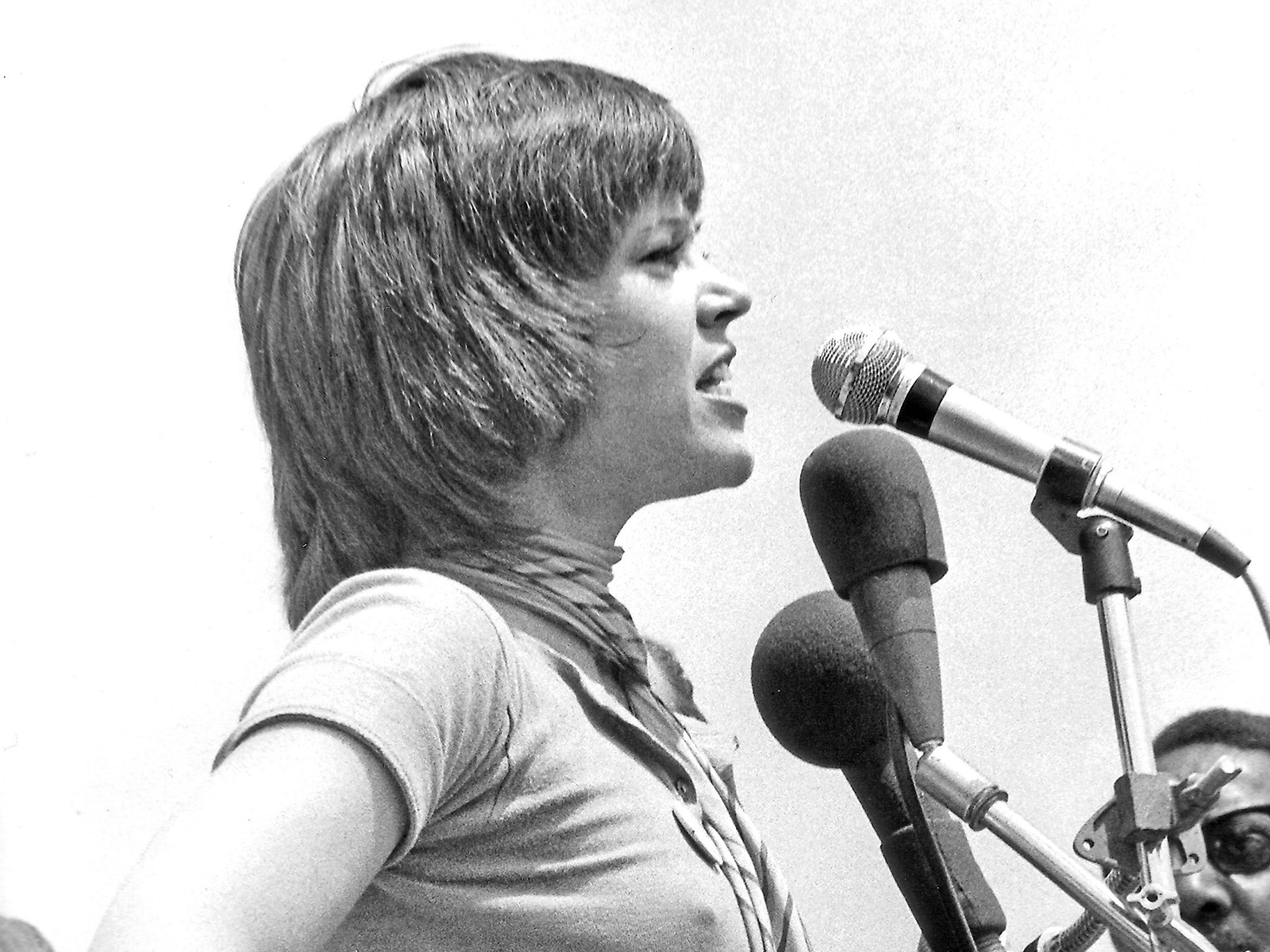

Jane Fonda, March 1971

In the past year and a half, Jane Fonda has completely immersed herself in radical politics, becoming active in, and lending her celebrity to, both social and political movements

SMITH: Since the last time we talked, there seems to have been an enormous change in your outlook and interests. What was the turning point? Was there one key incident?

FONDA: No. What I didn’t tell you at that time was my marriage was breaking up, partly because of things which I now see in a more political light. I went through a process of change, which began on a personal level and then had ramifications politically. It had to do with things that I became aware of while living in Europe. We had early-on access to information, films on French television showing B52 bombers dropping anti-personnel bombs on North Vietnamese villages that had just churches and schools and hospitals in them. I began to read information and talk to soldiers who were coming back from Vietnam, work with deserters in Paris – and for the first time began to understand, helped by the incredible change in attitude towards America that was taking place over the years I lived there.

When I went there, it was during the Kennedy administration and America was looked to with great hope as being a place that could, perhaps, become what it professes to be on paper. When I left, the hatred for what America stands for was terribly difficult to confront. And one of the reasons that I came back was because I realised that my place was here. That there were things that I felt I wanted to fight for, not just in a from-time-to-time, sporadic, isolated kind of way...I was also very close to doing a drop-out metaphysical type of trip, because of the cynicism and sense of hopelessness and disillusionment about this country.

I guess what stopped me is that I went to India. And I went to India for the same reason that lots of people go to India, seeking some sort of metaphysical answer. I found abject poverty and total misery. I found white middle-class American hippies living in the midst of this poverty, spaced out on drugs, making the situation worse, and totally insensitive to the problems that the Indian people are facing. And when I would talk about this, these people would say, “You’re just bringing your middle-class values here. They don’t consider sleeping in the streets and starving the same way you do.”

And I realised how irresponsible that whole drop-out, put-blindfolds-on way of life is. The country had really changed in the six years that I was away. And many people had gone through political evolutions that I hadn’t experienced. So when I came back I was confronted with a whole new situation and, in a very short space of time, tried to understand why this had happened and made contact with certain kinds of people: American Indians, militant and nonmilitant, the Panthers, soldiers... People told me, “Your career will be ruined.” “You’ll be killed.” And I found a group of intelligent, sober, dedicated revolutionaries who were dealing with root problems in the country.

SMITH: You feel you’ve moved from liberalism to radicalism?

FONDA: To understanding that it’s my life I’m fighting for... All of these things that I had viewed as isolated issues, like racism, poverty, unemployment, the war in Vietnam, the Indian problem here, and the Chicano problem there, were in fact the same thing. That they were the same thing that was messing me over as a white American woman, that was making it difficult for practically anybody in this country to have any kind of self-determination, any kind of control over their lives.

Jerry Rubin, October 1971

In February 1970, Jerry Rubin was convicted of crossing state lines “to inspire riot” at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Last month inmates at Attica State Prison seized control and issued demands to improve their quality of life. After a four-day standoff, the chief of the state penal system, Russell Oswald, with the consent of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, ordered in the National Guard. Of the 43 killed, ten were hostages accidentally shot by the guard

SMITH: How you doin’?

RUBIN: Great. Rockefeller and Oswald were just indicted for murder.

SMITH: They were? Who indicted them?

RUBIN: The people of the state of New York, in a transcendent trial that went beyond the court system, because the court system won’t bring ’em to justice.

SMITH: Where was it held?

RUBIN: In Brooklyn at a hotel, in a courtroom, and there were judges and they were all represented. They were asked to show up, and they didn’t show up. So people acted in place of them, but just said the lines that Rockefeller and Oswald – and Nixon, who was also indicted for murder – have said publicly. And the jury was about 13 seconds before it returned its verdict, because the evidence was so clear that Rockefeller and Oswald just murdered 43 people.

SMITH: Something I’ve been wondering, and I wonder what it looks like from your position at what I think must be the centre of – “The Movement”? “The Revolution”? I don’t know what to call it...

RUBIN: No, flank. We’re a flank.

SMITH: Is it all over?

RUBIN: Oh, no, definitely not. It went through a bad year. But San Diego will be the biggest human explosion that’s ever taken place in the country. Nixon hasn’t solved any of the problems. But... people don’t demonstrate because they know they’ll have no influence, no effect on Nixon. And then people get very depressed, and that’s what’s happened... I think the Kent State murders [when the National Guard fired on student demonstrators] were, like, the end. ’Cause then people saw, “We’re gonna get killed and we’re gonna have no influence.” So people got very internal, started examining their own lives. But good things’ve been goin’ on, too. The growth of communes, women’s liberation, gay liberation... The public, visible demonstration aspect was killed by repression. But it’s only temporary.

SMITH: You don’t think there’s a possibility that the reason why everything kinda fizzled out is that people were treating it as a fad, and the fad is over?

RUBIN: No, definitely not, because people’s real lives are totally involved... And it’s gonna go on. There’s gonna be a revolution in this country. There’s no doubt about it. The capitalist imperialism is gonna be destroyed.

SMITH: Even though so few people show up at demonstrations?

RUBIN: If you look to the Russian Revolution and the Cuban, there was a big splurge and then it went dead for about two years. And then, boom: the revolution. There are historical parallels for what’s goin’ on right now. Everything goes in cycles…

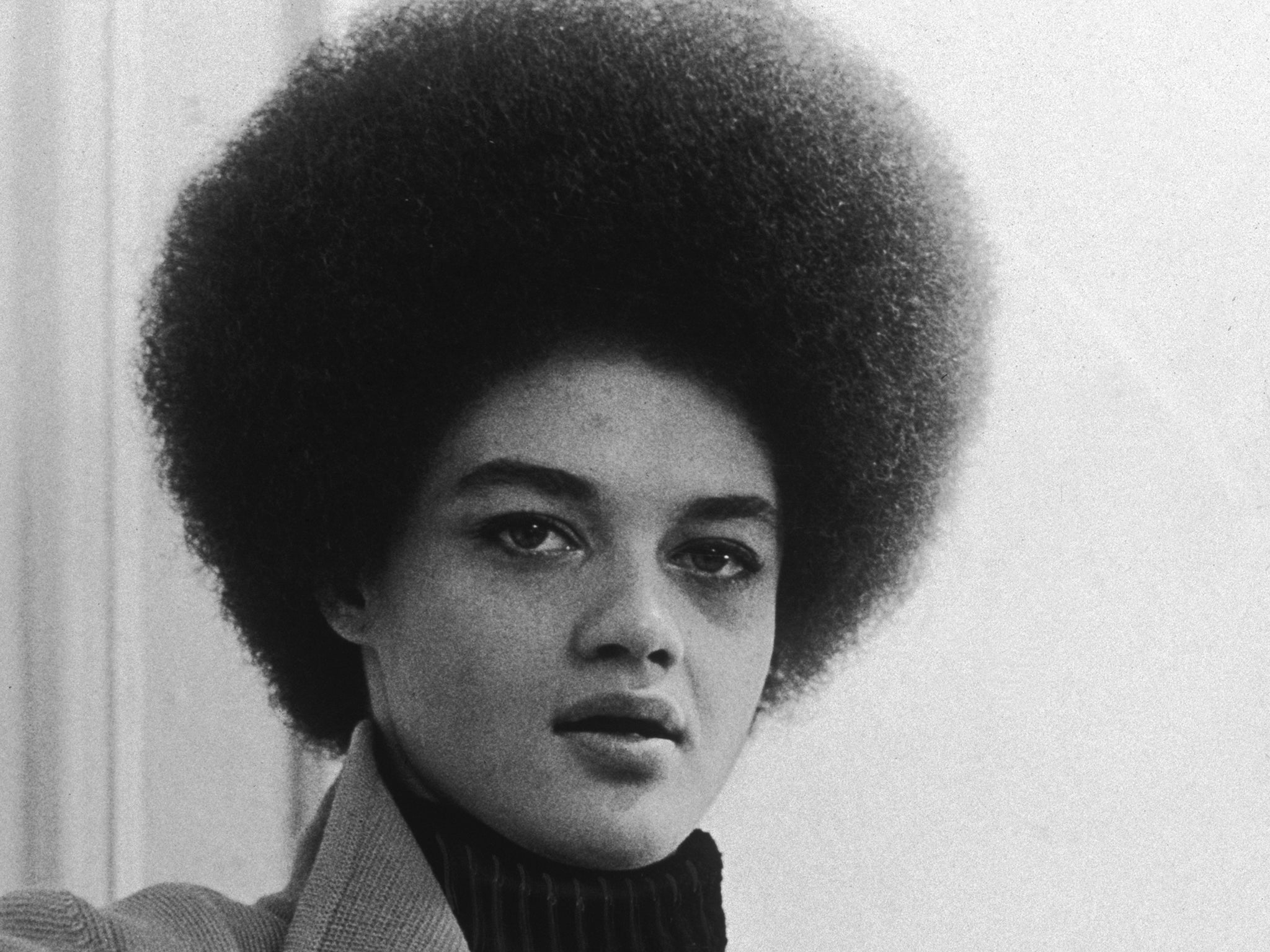

Kathleen Cleaver, November 1971

In 1968, the Communications and Press Secretary of the Black Panther Party (BPP) fled the US for exile in Algeria with her husband, BPP Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver, to escape his arrest on charges of attempted murder of police officers.

This March, they were expelled from the BPP and have now formed the Revolutionary People’s Communications Network (RPCN). Kathleen has just returned, to begin publishing RPCN’s new newspaper “Right On!” out of an apartment in Harlem

SMITH: How about the split at this point between the two [Panther] factions?

CLEAVER: The contradictions became too blatant for the movement to change to a higher level, and the movement to stay at a certain position and be more conservative, more legal, more involved with the system – it became too blatant to allow the two different aspects to continue to operate in the same organisation.

SMITH: It seemed to become quite violent – it wasn’t just an intellectual –

CLEAVER: Not at all. It’s a structural problem. It was a methodological problem. And also the leadership in the West is a conservative element that was moving in opposition to the bulk of the people who formed the party and made the BPP a reality, [and they] found it necessary to wage war against people who took outright opposition to them. It had gone from a situation of purge, expulsion, denunciation, to killing.

SMITH: Are you in danger at this point yourself?... Do you take precautions?

CLEAVER: Yes... we recognise that we have all types of enemies within and without.

SMITH: Do you feel that you are treated as an equal by the men that you’re associated with?

CLEAVER: I feel that I’m treated with as much respect as they feel that I have earned.

SMITH: But do you feel that they treat you with as much respect as you feel you’ve earned?

CLEAVER: Well, no, because I’m a woman. And I see that many people still have not managed to bring their practice totally in harmony with their theories. But I don’t see anyone that’s consciously and deliberately trying to put me down or make me inferior or be chauvinistic towards me simply because I’m a woman.

SMITH: PLJ [eg, “caller”], Howard Smith. You’re on the air. Turn your radio down.

CALLER: You said something about an inevitable civil war coming in the 20th century. It seems to me that the black population is so outnumbered by the white population that they would get completely destroyed and end up in a worse position than they are now.

CLEAVER: We’re not such a small minority of the population. You seem to feel that the black people are the only people that feel this way in this country. There are at least 40 million black people in this country, and you tell me if one-half – 20 million – participated in a revolutionary civil war, what forces are there going to be used to oppose us? The US military apparatus involves about three million men. The US police forces involve about one and a half million –

SMITH: But they have all the weapons.

CLEAVER: They had all the weapons in Vietnam; they’re still being moved against. They still haven’t won, you see?... One thing that people fail to recognise is that when there’s a civil war, it’s against the government, not against the people. And the government is the most profound minority in this country. µ

These are edited extracts from ‘The Smith Tapes: Lost Interviews with Rock Stars & Icons, 1969-72’, by Ezra Bookstein (Princeton Architectural Press, £14.99), out Tuesday 20 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments