How to disappear completely

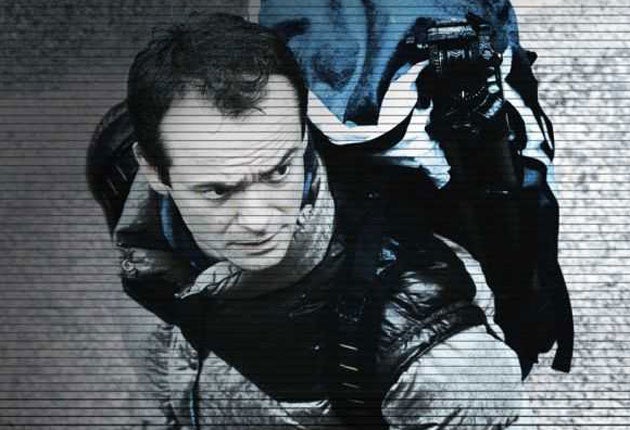

Is it possible to slip the net of today's surveillance society? Film-maker David Bond went on the run to find out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.My name is David Bond. I am an average 38 year old, married with two children. We live in Hackney, London. I pay my council tax. I've never been in trouble with the police. There are no skeletons in the closet. Yet last year I went on the run from two private investigators whose job was to find and grab me. It was an experience I do not want to repeat.

Details about my family and me are on around 700 company and government databases. I am caught on CCTV cameras 300 times each day. Until recently I did not give this a second thought. Why should I worry? Then a letter from the Child Benefit Agency arrived. It said that they had lost my daughter Ivy's data – and with it my bank details. She was four months old.

Thirty years ago, very little data was kept on British citizens – but now all that has changed. With support from the Channel 4 BRITDOC Foundation and The Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, I have completed a feature documentary about the issues. It is called Erasing David. My producer hired Cerberus, a top firm of private investigators, to track me down. All they had to go on was my name and a recent photograph. I was to try to avoid being physically caught by them for 30 days.

My first move was to get out of the UK to leave a cold trail as soon as possible. I booked tickets on Eurostar in another name, and changed them to mine at the last minute. I visited Paul Rusesabagina in Brussels. Hotel Rwanda is based on his experiences. He has a strong aversion to ID cards. During the 1994 genocide, killers used them to distinguish Hutu from Tutsi at roadblocks. "You can never know how data will be used in the future," he said. "It is a very powerful weapon."

From there I went to Berlin and met with Jörg Drieselman, a survivor of Stasi surveillance and torture and the director of the Stasi museum. He is amazed at the lack of resistance by the British public to our growing database state. "It is very easy to establish a dictatorship, and to keep it alive," he told me. Drieselman also warned that if the investigators were any good, they would use my family to get to me.

Heading back to the UK, I had a bad feeling about my Eurostar ticket – and opted for the ferry. It was a lucky instinct. Cerberus was waiting for me at St Pancras station.

Over the coming weeks, I slept less and less, and became increasingly paranoid. Before setting off, I had visited Dr Daniel Freeman, an expert on paranoia, at King's College London. He warned that I would adopt a paranoid style of thinking while on the run – although, unusually, in my case there really was someone after me.

We are beginning to see the early victims of our brave new database world. I met a young woman, Emma Budd, who is persistently confused with a shoplifter by the criminal records bureau, and denied jobs. The stakes can be higher, though. Josephine Chong's son Robert killed himself after being wrongly arrested for an indecent act.

We all give away a little more data than we should. The congestion charge was introduced to reduce traffic in central London – so why do the automatic cameras used store and share cars' movements with the police? Data is easy to collect and very hard to control.

I will not say whether Cerberus caught me within the month. Watch the film. But after the month was up, they led me into their control room. One large wall was covered with information about me. They had a detailed personality profile that allowed them to predict what I might do. And all this was publicly available information. All of this is out there about you, too. Our personal data is a profound possession of ours. We should keep it safe.

'Erasing David' is released in cinemas nationwide on 29 April and broadcast in More4's 'True Stories' strand on 4 May at 10pm ( Erasingdavid.com )

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments