The rise of therapists on TV, from Wanderlust to Homecoming

As stigma around mental health softens, and record numbers of people seek help, this is being reflected in the stories told on screen

“I’m David, and I need some help.” That statement by Bodyguard’s David Budd – heard by the record-breaking 11 million people who tuned in to watch the BBC1 series finale – was a powerful moment on television. We so rarely see action heroes accepting that they have issues to work through. And while we weren’t privy to whatever discussions Budd had with his counsellor about his PTSD-inducing time in Afghanistan, it was enough just to know that he was having them.

As stigma around mental health is slowly but surely softened, record numbers of people are seeking help. According to the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy’s most recent study, more than a quarter (28 per cent) of people in the UK consulted a counsellor or psychotherapist in 2014, compared to just one in five in 2010. It’s no surprise then, that this is being reflected in the stories told on screen.

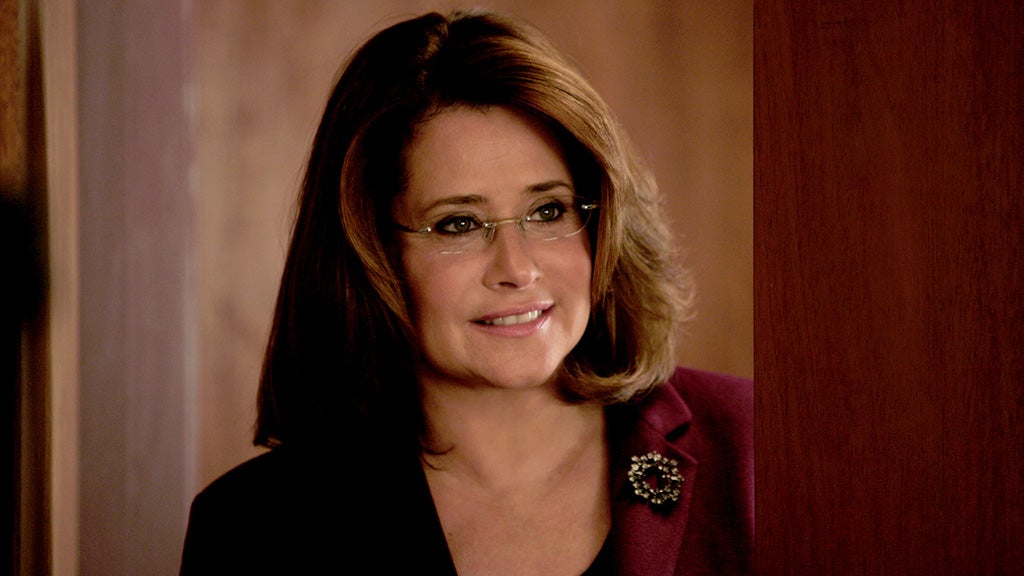

Therapy has played an important part in a number of recent TV shows, from realistic depictions in Wanderlust and Big Little Lies to more fanciful ones in Maniac and Homecoming. In the latter – which arrived on Amazon Prime on Friday – Julia Roberts plays Heidi, a counsellor helping soldiers rehabilitate back into society. It’s hyper-stylised and a world away from Bodyguard’s examination of PTSD.

Therapy is clearly a fascinating proposition for storytellers. It offers a chance to get inside a character’s head without narration, and the fact that therapy sessions tend to be weekly lends itself well to episodic formats.

The Sopranos was one of the first shows to exploit this effectively, as Dr Jennifer Melfi tried to figure out Tony Soprano almost in real time. The mob boss brought whatever was going on with his business or family on a given week into every appointment with him – sometimes overtly through discussion, sometimes indirectly – and the events outside the therapist’s office affected his honesty, patience or belief in the process. A depressed mafioso who suspects therapy is a load of baloney, but is too sad and angry not to give it a shot, was an irresistible setup. Soprano’s interactions with Melfi often served as anchors to episodes, and the show would have been unimaginable without them.

As a profession, though, therapists don’t come off so well. In Homecoming, Heidi chats informally with her patients to the point of unprofessionalism, and you can see her internalising their predicaments, the focus being on how they affect her. The Sopranos was full of deeply flawed characters and Melfi was no different, frequently betraying her patient’s confidence, flirting and letting her emotional investment in him cloud her judgment. She almost had Soprano kill for her, and her obsession with her most unusual patient landed the therapist, somewhat ironically, in therapy.

I can’t imagine any TV writer wanting to contribute to confusion and stigma surrounding mental health, but having a therapy session go down with unwavering realism is unlikely to work from an artistic, storytelling standpoint. Portraying mental health treatment is an incredibly tricky line to tread. Conscious of this, mental health charity Mind has hired dedicated advisors to offer guidance to television and filmmakers.

“Mental health is definitely being explored more proactively in TV soaps and dramas these days and, importantly, it is also being portrayed far more authentically than in previous times,” says Jenni Regan, media engagement manager for Mind.

“It’s not perfect, and there has to be a balance between drama and reality, as there does with any subject. However, portrayals that are stigmatising or that have the potential to negatively impact viewers are, thankfully, in decline."

On TV, therapists have often been portrayed as pompous. They’ve been to medicine what scarf-wearing thespians are to the arts. Take Arrested Development‘s Tobias Fünke, and both of Frasier‘s Crane brothers. There is also the issue of authenticity. The therapists of television shows also tend to be existing characters, serving as protagonists’ colleagues or friends one minute and their therapists the next (eg Star Trek‘s Deanna Troi).

It can lead to false perceptions, Regan explains. “One of the conflicts you sometimes find with soaps or dramas and reality is that everything happens in one place, so the therapist, or even GP, is sometimes a neighbour or friend of the person they are working with. Of course, in reality, this is highly unlikely and there are professional boundaries, but again, it’s that balance between drama and authenticity.“

Authenticity is perhaps most strained when a character agrees to seek help, and then is in a chair behind a box of tissues in the very next shot.

“We also advise on waiting times, since NHS referral times for talking treatments aren’t instant, and this sometimes conflicts with a need to move the story forward,“ Regan says. “However, we work closely with script researchers and writers and there are often different ways of showing support for a character without suggesting referral times are immediate, which could raise unrealistic expectations with viewers.”

Therapy is often portrayed accurately when it’s a major part of the show, or even central to it, as was the case with HBO’s In Treatment. Protagonist Dr Paul Weston is – like Melfi – a therapist in therapy, but rather than analysing organised crime the show offered, as The New York Times put it, “an irresistible peek at the psychopathology of everyday life”. Nevertheless, it is possible for shows to incorporate only minor therapy narratives without lapsing into cliché.

Real-life therapists loved Big Little Lies‘ Dr Reisman, who counselled Nicole Kidman’s Celeste when her marriage turned violent.

“She’s not using the stereotypical tools – she’s not just saying, ‘Oh, and tell me how that makes you feel’ and those kinds of things over and over,” licensed therapist Erin Qualey told The Cut. Not only that, but Reisman didn’t become obsessed with the details of the complicated psychosexual issues Celeste and her husband had, which is a common trap when a screenwriter is trying to examine juicy character interplay. Instead, the doctor focuses on a plan for Celeste to escape husband Perry, calmly advising her patient to rent an apartment and stock the fridge – a refuge for when she feels ready to leave.

Wanderlust also sought to do away with the “and how did that make you feel” stuff. This show’s therapist avoided trying to extract huge revelations about, or establish causal links between, the events Toni Collette’s Joy wanted to discuss and how she was feeling.

“Overall, it’s great to see talking therapy being portrayed in dramas, as it more accurately represents the holistic nature of treatments that are available for mental health problems, rather than relying on the idea that medication can solve everything,” Regan concludes.

The appeal of a therapist’s office from a screenwriting and cinematography point of view has led to hundreds of them appearing on screens. Medication is, however, a form of treatment given considerably less screen time. And when it is, it’s often through the image of anti-depressants being gobbled from little yellow pill bottles as characters stare intently into the bathroom mirror. As TV creators continue to depict therapy on our screens with more empathy and authenticity, portraying mental health medication as something more three-dimensional than a mere numbing agent might be the next challenge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks