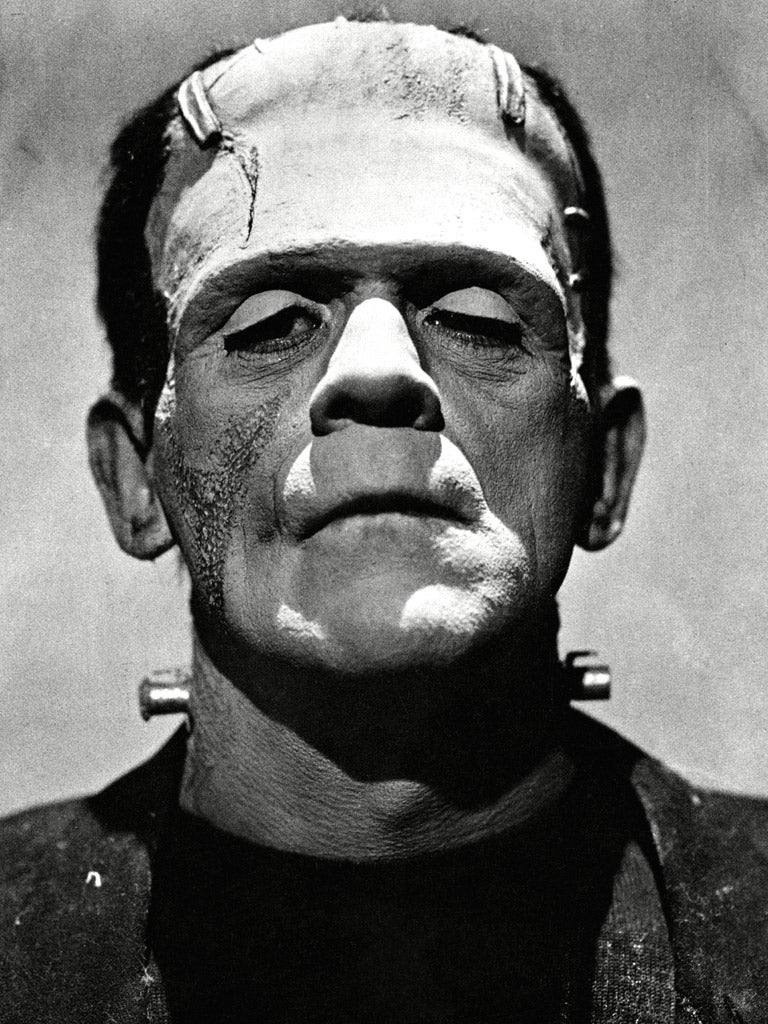

Frankenstein's monster: Why gothic is more popular than ever

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein still stokes our fear of apocalypse, bad science and corruption. As a new documentary looks at its cultural legacy, Philip Hoare explains why gothic remains a perennial theme

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gothic remains a perennial theme but never more so than today. Why so? For one thing, the gothic imagination of writers such as Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe and Bram Stoker is so vividly visual that it is eminently adaptable into 21st-century media – from cinema to TV to video games. Also it reflects teenage angst – Shelley was just 17 when she wrote Frankenstein.

But it also reflects deeper contemporary fears of the apocalyptic and the macabre: of bad science and corrupt power. It reflects dark times, too, and offers escapism from austerity or insecurity – a safe, containable way to be scared. Most of all, perhaps, it addresses dark themes of psychosexuality. This autumn the gothic is everywhere: from Radio 4's Gothic Imagination to Tim Burton's Frankenweenie, and, tomorrow night, a new Channel 4 documentary examining the Frankenstein myth screened, fittingly, on Halloween.

My own first intimation of the gothic came with the 1922 German expressionist film Nosferatu, which I saw on our crackly black-and-white TV one sunny afternoon in the 1960s. Later, I'd attend college in Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill on the banks of the Thames – a castellated confection that sparked off the 18th-century craze for the "gothick", fuelled by the stories of Matthew "Monk" Lewis, Mrs Radcliffe, William Beckford, and Walpole himself. (I can even boast that my own grandfather, born in Whitby in 1891, lived two streets from where Bram Stoker was then writing Dracula.)

But more than anything, it is the myth of Frankenstein and his monster that has lodged in the popular mind – to the extent that Hurricane Sandy has been dubbed "Frankenstorm". Shelley's story has inspired everyone from Herman Melville to James Whale, from Mel Brooks to Robert Harris, and, most recently, Danny Boyle for his hugely successful National Theatre production. It was this that inspired award-winning director Adam Low to make tonight's film, Frankenstein: A Modern Myth. Featuring interviews with Benedict Cumberbatch (who also narrates the film), Jonny Lee Miller and Danny Boyle, among others, it delves deep into the psychological and cultural resonances of the most famous of all gothic stories.

Like Moby-Dick and Wuthering Heights, Frankenstein is a unique, sui generis work, born of obsession. It feeds on sensational, science-fiction elements to make subtler points about our essential disconnect with nature. It's why Shelley's image of the Creature – as much pathetic as it is terrifying – is invoked ever more often in contemporary culture and a world in which science and technology appear to be stealing a march on the species that created them. Last year, commentators evoked Frankenstein when the Japanese tsunami broke open the Fukushima nuclear reactors.

What is extraordinary is that all this was the product of the mind of a woman barely out of girlhood. Storms attended her life: from her illicit start as the bastard child of the revolutionary writers William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecroft, to the climatic catastrophes in the year of her birth and that of her novel, which coincided with a volcanic eruption that darkened the skies of Europe and America. "She entered the world like the heroine of a gothic tale," Shelley's biographer, Emily Sunstein has written, "conceived in a secret amour, her birth heralded by storms and portents, attended by tragic drama, and known to thousands through Godwin's memoirs".

At 16, she ran away with Percy Shelley to Europe, and holed up with Lord Byron at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva. In a bravura sequence, Low's film compares the Shelleys and Byron to rock superstars, like the Rolling Stones in their decadent pomp and satanic majesties. Byron always carried a condom; Mary's half-sister, Claire Clairmont became his lover, and bore his illegitimate child, even as she professed her love for Percy Shelley, too.

Here in "sublime, awfully desolate" Switzerland, these bohemians set up a kind of commune, "a modern Promethean cadre", watched all the while by tourists through telescopes on the other side of the lake, mistaking the laundered tablecloths for the womens' soiled petticoats. The press dubbed them the "Vampyre family", "that knot of scribblers, male and female, with weak nerves, and disordered brains, from whom have sprung those disgusting compounds of unnatural conception, bad taste, and absurdity". If they'd had mobile phones, they'd certainly have been hacked.

Frankenstein came as a shock tactic, a perverse first novel. It was heavily edited by Percy Shelley – the original manuscript in the Bodleian Library, shows how the poet added words and crossed out others, striking out Mary's description of the Creature as "handsome" and substituting an emphatic "beautiful". But Mary Shelley had the power of expression, and as a teenage girl was empowered by words as much as by her bizarre upbringing. Literature represented liberation for her sex, as her mother taught her, from beyond the grave.

Low's film takes its cue from the recent, hugely successful National Theatre production, in which Cumberbatch and Miller appeared on alternate nights as Victor Frankenstein and his Creature (who, in a memorable opening scene, appears naked). From there, Low proceeds in a typically eclectic manner, mixing interviews with scientists and biographers with fictional representations, culminating in a hilarious interview with director John Waters who declares his love for "The Monster Mash", a 1960s hit that he performs as his party piece. It's a tribute to Hollywood's assimilation of the myth. "I'm sympathetic to monsters," says Waters, "and this was the first one I came across as a child."

Somewhere between these wild extremes lies the essential strangeness of Mary Shelley's legacy. Her novel, which emerged from a dream, is an expression of defiance, a blasphemous book that almost accidentally had huge reverberations into the future. Other dystopian visions have faded with time. But Shelley's prophetic and often violent fantasy, written almost 200 years ago, remains as powerful as ever – if not more so.

'Frankenstein: A Modern Myth' is broadcast tomorrow at 11.10pm on Channel 4

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments