Family Guy at 20: Is Seth MacFarlane’s deviant dad still a man for all seasons?

As the controversial cartoon turns 20, Ed Power looks at its creator's journey from 25-year-old wunderkind to the clown prince of Hollywood

Throwing punches at Donald Trump is a favourite pastime of the American entertainment industry. But calling out the president’s hypocrisies has proved problematic for animated comedy Family Guy, which marked its 20th anniversary by recently staging an onscreen fight between Trump and its own obnoxious anti-hero, Peter Griffin.

“Many children have learned their favourite Jewish, black, and gay jokes by watching your show over the years,” a Monster Munch-hued cartoon Trump tells Griffin.

“We’ve been trying to phase out the gay stuff,” replies Griffin. “But you know what? We’re a cartoon. You’re the president.”

With “Trump Guy”, Family Guy was clearly keen to join in the liberal backlash against the commander-in-chief even as it hand-waved aside its own forays into bad taste. What resulted was a masterclass in Hollywood cakeism from a series that today celebrates two decades of taboo-tweaking.

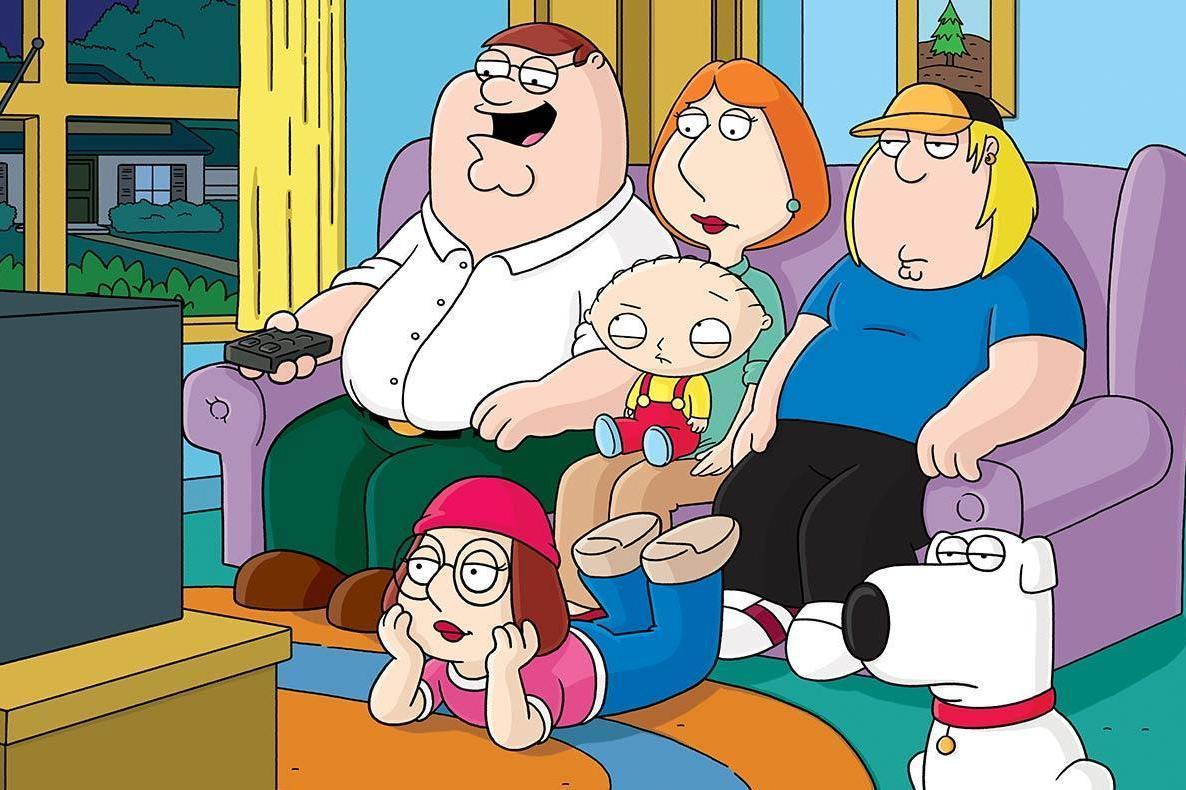

But so has it ever been with Seth MacFarlane’s homage to/rip-off of The Simpsons. Since 1999, Family Guy has followed the adventures of Quahog, Rhode Island, dad Peter Griffin, wife Lois, and children Meg, Chris and villainous baby Stewie, and their laconic dog Brian.

MacFarlane provides the voices of Peter, Stewie – who sounds like Dr Evil by way of Kenneth Branagh – and Brian the Dog (the closest to McFarlane’s actual speaking tones). Mila Kunis is the best known of the actressess to portray Meg, while Family Guy writer Alex Borstein plays Lois and actor Seth Green (Daniel “Oz” Osbourne from Buffy the Vampire Slayer) dunderheaded Chris.

Their performances are typically lighthearted – though not to the point where it conceals the often hardcore humour. Family Guy and spin-offs American Dad! and The Cleveland Show have merrily indulged in every imaginable gay, transphobic and ethnic joke (and a few unimaginable ones too).

Family Guy has done this even as MacFarlane has polished his credentials as an archetypal left-leaning Tinsel Town good guy. He has donated millions to causes such as American public radio and has campaigned for gay marriage.

The contradictions between his high-minded ideals and no-brow humour are clear. But, as the now 45-year-old MacFarlane surveys his $250m fortune, his 2013 gig hosting the Oscars and parallel career as Sinatra-style crooner, he may conclude that he’s done well for a blue-collar kid from Connecticut.

Family Guy splashed down on a Sunday night, straight after John Elway led the Denver Broncos to the 1999 Super Bowl. The post-Super Bowl slot is among the most valuable in American broadcasting. Fox, keen to build on the success of The Simpsons, had plucked 25-year-old wunderkind MacFarlane from the obscurity of the Hanna-Barbera animation department and was wagering heavily on his youthful ambition.

Healthy first-night ratings of 22 million suggested the network’s confidence was well placed. Yet from the start Family Guy felt more throwback than leap forward. In the very first episode Griffin is sacked after drinking 38 beers at a stag party and then falling asleep at his job at the toy factory. He ends up in prison, where MacFarlane can’t resist a joke about “dropping the soap” in the shower.

There is also a gag about “GI Jew” – a toy soldier whining about bagels in a stereotypical Woody Allen accent. One week later, Family Guy confirmed its march against polite sensibilities with a scene in which a news anchor, believing she is off the air, looks at the camera and says, “I just don’t like black people.”

It was Family Guy’s way of revealing to viewers that this was going to be a very different rollercoaster from The Simpsons. Season two starts with Peter suspecting that the butler who has baked him a cake might be gay. Later came episodes with names such as “Down Syndrome Girl” and “Iraq Lobster”. In 2004, MacFarlane, again voicing Griffin, would sing “I Need a Jew” – to the tune of “When You Wish Upon a Star” and containing the line “even though they killed my Lord”.

“How do you know I’m an accountant?” asks a character in the same instalment. “Hello…” responds Griffin. “Max Weinstein.”

MacFarlane later defended “I Need a Jew”, stating he had screened it for two rabbis prior to airing. He added that “70 per cent” of his writing staff were Jewish.

But he generally shrugged aside the outrage and carried on. His resoluteness in the face of public outrage was hardened, it is tempting to conclude, by a remarkable narrow escape from the 9/11 World Trade Centre attacks. Waking hungover after a speech at his alma mater, Rhode Island School of Design, he had arrived late at Boston’s Logan airport and narrowly missed his flight to New York.

MacFarlane fell asleep in the departures lounge and was roused to discover a crowd gathered around a TV. The plane he’d been booked on had just flown into the second tower of the World Trade Centre. He’d cheated death by 10 minutes.

Live through something like that and a backlash about politically incorrect humour must seem trivial by comparison. The experience certainly didn’t put him off 9/11 jokes, with which Family Guy and the 2012 live-action hit Ted are packed.

Even harder to defend than “I Need a Jew”, it might be argued, was the notorious 2013 episode, “Turban Cowboy”. Here Griffin befriends a Muslim who of course turns out be a violent jihadist.

“Turban Cowboy” concludes with the hapless Peter driving through the Boston Marathon, ploughing down runners. It has, for obvious reasons, been withheld from broadcast since the Boston bombings of later that year.

Despite – or possibly because of – such gratuitousness, Family Guy has become one of the television’s most beloved animated comedies, arguably second only to The Simpsons. True, ratings were initially less than spectacular. Many of the 22 million who tuned in after the Super Bowl did not return. By the end of its first season, Family Guy was languishing at 33rd place in the Nielsen countdown.

But soft viewership obscured the depth of the devotion MacFarlane was building among a hardcore following. The intensity of the Family Guy fandom was confirmed when Fox cancelled the show in 2002 – having delivered the kiss of death by pitching it against Friends on Thursday nights – only to bring it back four years later.

The catalyst for this unlikely rebirth was the airing of repeats of seasons one and two on Adult Swim, which boosted that channel’s ratings by 600 per cent. Sales of Family Guy DVDs rocketed too. In one month alone in the US, a boxed set of the first and second seasons shifted 400,000 copies. Fox realised that it had killed the golden goose – but that it had the opportunity to bring it back, which it did in 2005.

Family Guy was by now making an unlikely star and heartthrob of MacFarlane, who has at various points been “romantically linked” with stars such as Eliza Dushku and Emilia Clarke. In 2011, he released his debut collection of big-band standards, Music Is Better than Words. By the time he hosted the 2013 Oscars – announcing that year’s nominees, he famously hinted at Harvey Weinstein’s predatory habits – he stood before the world as an old fashioned song-and-dance man.

MacFarlane’s origins are humble and he is as close as Hollywood comes to a self-made success. His father was a teacher, his mother a career guidance councillor. A talented cartoonist from childhood, he received a scholarship to the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, where his jock mannerisms (he wore a rugby shirt to class every day) and infantile humour set him apart.

His crowning achievement at RISD was his final year project. A Peter Griffin-esque everyman idiot goes to see Aids drama Philadelphia and breaks into laughter when Tom Hanks’ appears on screen and declares he is terminally ill (the gag would be recycled by Family Guy). Amid the endless dour art-house movies it stood out like a streaker at a funeral.

This led to a gig at storied (albeit ailing) animation house Hanna-Barbera (which would finally shut down in 2011) and a pitch meeting at Fox. He screened for the execs Life of Larry, his crudely animated proto-Family Guy, and presented his case for a show that would be similar to The Simpsons, only far less tasteful.

They bit – partly because MacFarlane agreed to do it for what was by prime time standards a minuscule budget. Upon shaking on the deal, he dashed out and called his mother, breathlessly informing her that Fox would pay him $1m a year.

MacFarlane’s juvenile streak has gone on to make him Hollywood’s pre-eminent clown prince. Outside of Family Guy, he had huge success with Ted and its 2015 sequel. And his Star Trek homage, The Orville, has won sci-fi fans over with its surprising sweetness (and the fact it’s far more faithful to Trek than the horrendous Star Trek: Discovery).

Yet none of this came easily. The critical response to Family Guy was negative, if not vicious. “The Simpsons as conceived by a singularly sophomoric mind that lacks any reference point beyond other TV shows,” went an early review in Entertainment Weekly. MacFarlane’s riposte was a scene in Family Guy in which Peter wipes his bum with a copy of the magazine.

Family Guy’s family of haters also includes other animators. South Park’s Trey Parker and Matt Stone critiqued MacFarlane’s reliance on non-sequitur cutaways, by which a joke is punched up by a blink-and-it’s gone juxtaposition. The quips, they suggested, were written at random by manatees. Parker elaborated in a DVD commentary that he and Stone “don’t like Family Guy”.

They were not alone – producers of The Simpsons and King of the Hill sent flowers to Parker and Stone after their takedown of the filthy-minded upstart. “There was this animation solidarity moment, where everyone did come together over their hatred of Family Guy,” said Parker.

“They can go to hell,” was MacFarlene’s response when speaking to radio host Howard Stern. “I try not to [get dragged into it]. We take so many shits on so many people I would be the biggest hypocrite in the world. They don’t like the way the show is set up. The cutaways… they don’t see that as a legitimate form of comedy.”

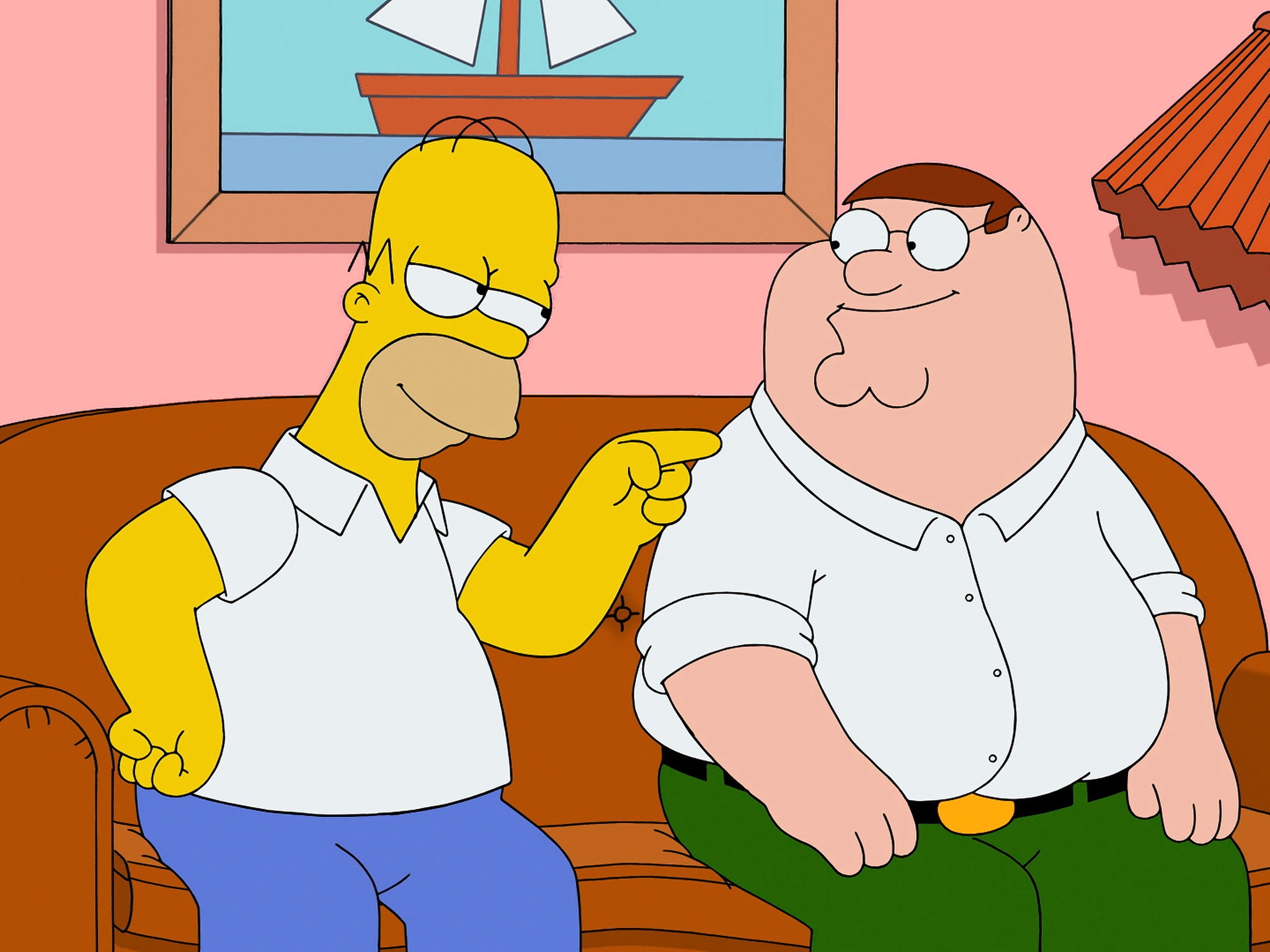

He pointed out in the same interview that his relationship with The Simpsons was more one of gentle ribbing than outright dislike. And indeed the two franchises put their differences aside for an (admittedly forgettable) 2014 crossover episode, “The Simpsons Guy”, in which Homer Simpson moves in with the Griffins.

MacFarlane has never apologised for his humour and often comes across as puzzled by the fuss. If people are laughing, he essentially declared to The New Yorker in 2012, what’s the problem?

“There’s a fairly broad spectrum of types of comedy that make me laugh. But, at the same time, if somebody farts in a room at the wrong time, I’ll laugh my ass off. And I maintain that that is a healthy, honest laugh. There is room for highbrow and lowbrow, and with Family Guy we try to embrace a balance between the two.”

He also excused using Peter Griffin as a mouthpiece for unacceptable views by essentially relying on the Alf Garnett defence. Just because a character says something offensive, it doesn’t meant that the writers necessarily support that perspective.

“We are presenting the Archie Bunker [the American equivalent of Garnett] point of view and making fun of the stereotypes – not making fun of the groups,” he said.

“But if I’m really being honest, then maybe there’s a part of me that’s stuck in high school and we’re laughing because we’re not supposed to. I don’t know the psychology. At the core, I know none of us gives a shit.”

There was a caveat: “Some people say that stereotypes exist for a reason. I’m in no way qualified to make that determination. But I’m sitting in a room with a writing staff that is in large part Jewish, and those are the guys pitching the jokes.”

Still, times change and Family Guy’s mockery of minorities has come to feel more and more out of step. The fun the show had teasing out the sexuality of pint-sized Bond villain Stewie – voiced by MacFarlane in the fashion of British silver screen star Rex Harrison – was both disconcerting and also simply strange. How can a baby be gay?

And there was an outcry over a 2010 episode in which sleazy neighbour Quagmire – very much a pre-#MeToo creation – wrestles with his father’s sex change.

The outrage largely flowed from a scene in which Brian throws up after sleeping with Ida and discovering she used to be a man. Called to task, McFarlane said: “All [critics] could lock onto was the fact that Brian threw up because he had had sex with Ida. Well, it’s a comedy, you know? I remember when I was a teenager thinking, ‘God, gay guys must be just as grossed out by vaginas as we are by penises.’ And that, in the simplest terms, is where Brian was coming from. It was a very simplistic point of view, but it’s a joke.”

MacFarlane’s empire has now expanded to the point where Family Guy is just one pursuit among many. He wrote, directed and starred alongside Liam Neeson and Charlize Theron in the 2014 comedy A Million Ways to Die in the West and released his fourth studio album in 2014.

Family Guy has meanwhile been renewed for at least another season. In terms of the show’s future, executive producers Alec Sulkin and Rich Appel have stated that they will dial down the homophobic jokes (”Some of the things we felt comfortable saying and joking about back then [the mid 2000s], we now understand is not acceptable”).

But would an inoffensive Family Guy really be Family Guy any more? If not, what sort of future does it have?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks