Wormwood's Errol Morris: This time I didn’t use my interview machine, the Interrotron

The Oscar-winning director explores the suspicious death of a US scientist caught up in a secret Cold War programme known as MK-Ultra in this six-part Netflix drama which stars Peter Sarsgaard

Errol Morris has been making documentaries in his own inimitable style for almost four decades. That perseverance must still come as a shock to German auteur Werner Herzog, who cooked and ate his own shoe when Morris proved him wrong and completed his debut film, Gates of Heaven, in 1978. Legend has it that Herzog wagered he would eat his shoe because he felt that Morris continually started projects but didn’t finish them. Director Les Blank recorded the feast for posterity when he made Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe.

It’s quite some way to start your directing career and the New Yorker, born in 1948, has continually challenged audiences with a series of insightful movies that have made him one of the most respected documentarians on the planet. His 1985 work The Thin Blue Line is often cited as the main reason that convicted murderer Randall Adams is walking free today.

Another of his films that make his contemporaries go misty-eyed when discussing Morris are the Oscar-winning The Fog of War, about the nature of modern warfare as seen through the eyes of the former US Secretary of Defence Robert S McNamara.

Morris’s new film, Wormwood, sees a change of direction for the director. It’s a work of fiction and a six-part TV series showing on Netflix. It’s Morris’s second stab at drama after the 1991 mystery thriller The Dark Wind, which was based on a book by Tony Hillerman. Morris never finished making that film because of reported clashes with executive producer Robert Redford.

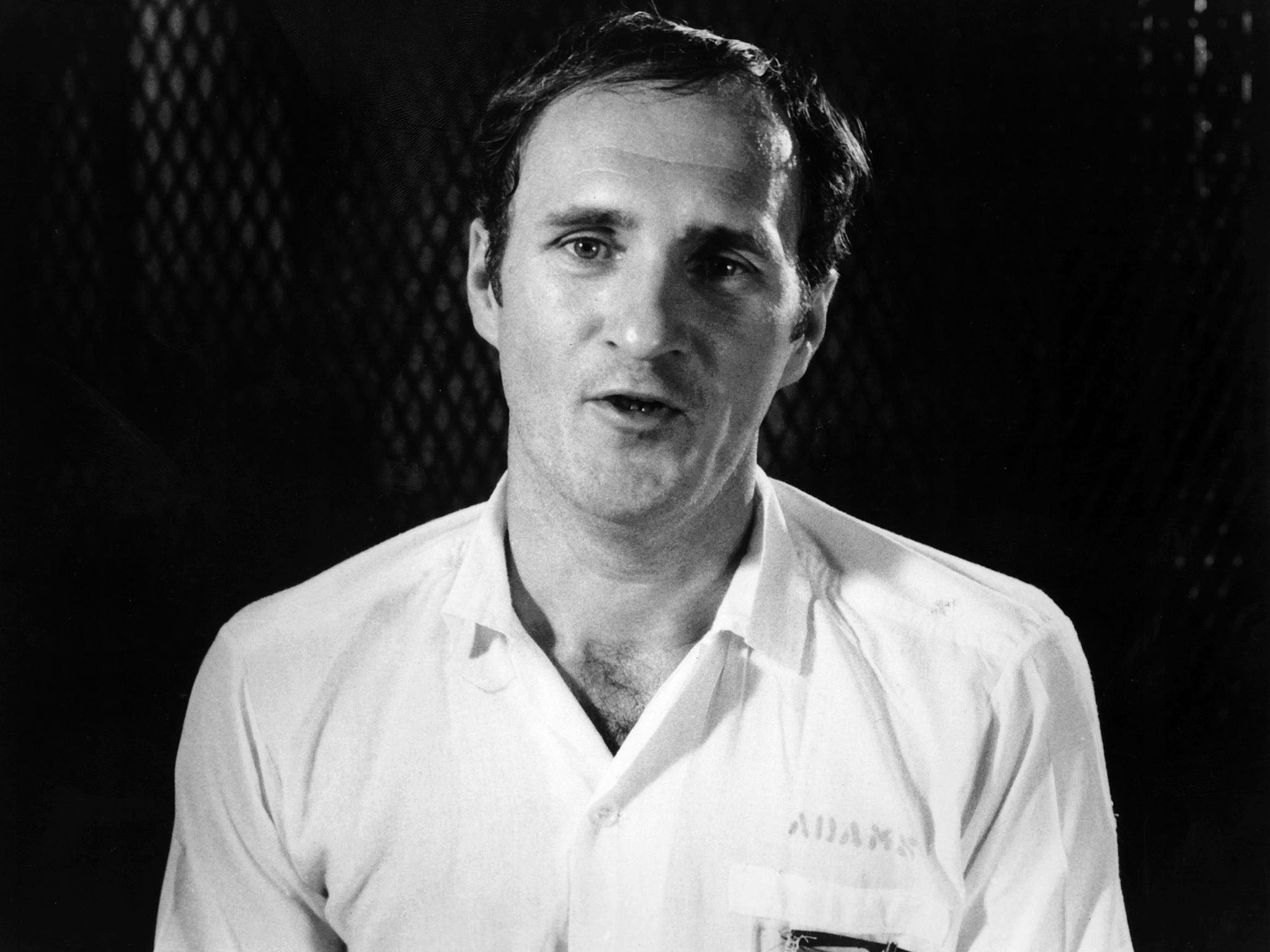

But while he makes the jump into fiction, his subject matter is in keeping within the context of his oeuvre. Wormwood revolves around Project MKUltra, the controversial CIA mind control programme that began in the 1950s and was only officially halted in 1973, in which experiments were done on human subjects, often illegally. It’s inspired by the six-decades-long campaign led by Eric Olson to uncover the truth about the death of his father, CIA bacteriologist Frank Olson, who was secretly being given doses of LSD as part of the programme. Nine days after these doses were first administered, Olson plunged to his death from a New York hotel room in a reported suicide.

He says that cover-ups are a by-product of government. “Lying seems to be an essential part of politics,” the 69-year-old tells me when we meet after a preview screening of the series at the Venice Film Festival. “Where would we be without it?” Morris’s career for one would look remarkably different.

He continues: “You want to see effective lying. One of the problems that I have with Trump – aside from the fact that he is destroying my country – is that he’s such a bad liar. You want your liars to have some kind of skill, you want them to get up and at least make the cursory effort that they are trying to tell the truth. You just look at him, and it’s liar, liar, pants on fire.”

The schoolyard phraseology of his argument could have come straight out of the Trump copybook. But while he is straight talking and occasionally blunt in person, Morris says that it was a struggle to tell this story succinctly in a drama. “There is a problem in all filmmaking and it’s a problem of exposition, especially in a story like this where there is a such a huge deposit of expository material: how do you handle it? Do you handle it through narration? The tricky business is when exposition is folded into drama it becomes intolerable.”

In the end he opted to follow the format that served him well with his documentaries. He mixes the re-enacted dramatic footage with fictionalised talking head interviews based upon the mountain of information that Eric Olson has collated over the years and his own research. So while this is a fictionalised account using actors – Peter Sarsgaard plays Frank Olson, with Molly Parker and Christian Carmargo in other leading roles – the dialogue is based upon real conversations and instances and the series contains Morris’s signature shot of talking heads talking straight into camera. Morris and Netflix have tried to argue with the American Academy that the resulting film should qualify in the Best Documentary category. They said no.

Morris says there is a major difference between these interviews and the ones in his documentaries that many viewers less attuned to the technical side of filmmaking may miss. “I didn’t use my interview machine, the Interrotron.”

The Interrotron is a camera system invented by Morris that uses mirrors and cameras to record conversations between Morris and his interviewees so that they can face each other in a room without a camera between them and yet what is recorded looks as though the subject is staring straight down the camera lens. For Wormwood, the famed cinematographer Ellen Kuras set up ten cameras that had to be positioned in such a way that they stayed out of the frame. For the docudrama re-enactments Morris had Igor Martinovic photograph the scenes with a wide-angle lens.

If there is a film noir flavour to the results, that’s because it’s the genre that Morris favours. The series even contains a line spoken by Robert Mitchum in the 1948 film Out Of The Past. Morris explains, “Years ago I programmed the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley. I was a compulsive movie goer and I was very much interested in noir.”

The film came about because Morris had heard that Netflix were interested in doing a film about MKUltra. He began working on a different story but switched to the Frank Olson tale as “I felt there was something there and I don’t know how it ultimately shapes out. I talked with Eric and he was capable of telling a compelling story and he had a vast quantity of photographic material, movies and stills, that his father had taken and then there was the 60-plus-year quest to solve the mystery of his father’s death.”

He’s happy that his foray into fiction has created a work that is unmistakably a Morris movie. Yet there were frustrations. “I wanted there to be more drama,” admits Morris. “It wasn’t as if I wanted a lot of interview. I felt that interviews were a way of going back to this whole question of exposition, of very quickly and efficiently providing information about the story. Roger Ebert once asked me what the difference was between drama and documentary and I said it’s very simple – two zeroes. The minute you start talking about setting things in 1953, which means wardrobe, cars and production design, the money involved multiplies quickly. I just wanted to do more and we didn’t have the budget that allowed us to do that.”

‘Wormwood’ is on Netflix on 15 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks