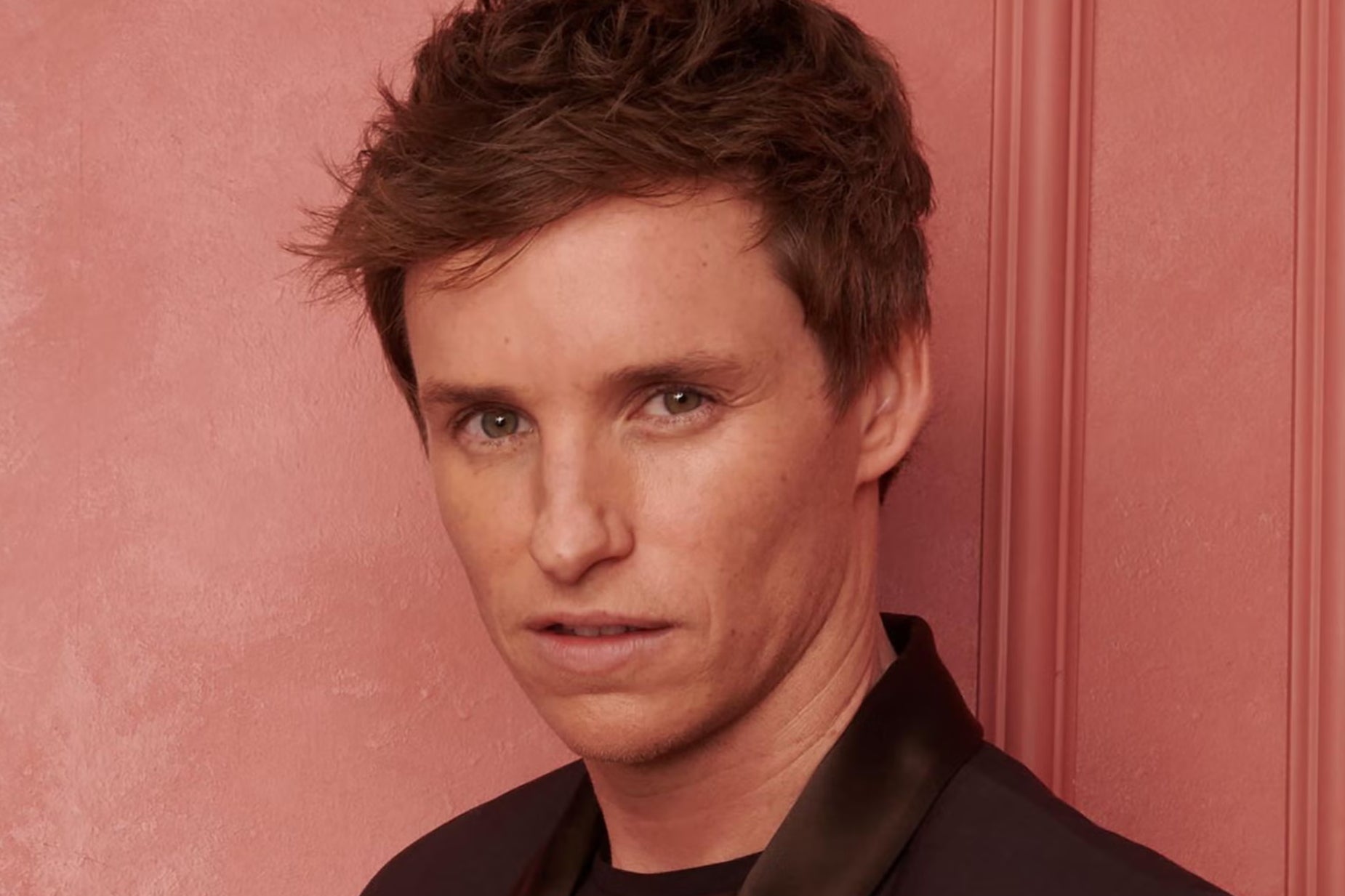

Eddie Redmayne: ‘I won a prize for worst performance of the year’

The Oscar-winning star of ‘The Theory of Everything’, ‘Fantastic Beasts’ and (gulp) ‘The Danish Girl’ is playing a hitman-for-hire in his new TV adaptation of ‘The Day of the Jackal’. He speaks to Adam White about famous friends, weathering backlash, and why the acting industry is ‘deeply unhealthy’

It’s an unseasonably warm October day in London, and Eddie Redmayne is gazing out of the window. I’m worried he wants to jump out of it solely to get away from this conversation.

“I suppose,” the actor stutters, “as any human would, you take each moment, each criticism, each interrogation, each, um... err...” He pauses. “Each opinion piece... um. Everyone’s voices...” He starts again. “Often something you’ve done is just a part of a much bigger discussion, and you try to make sense of it with the understanding and comprehension of any human being.” Redmayne turns back to me. He clears his throat.

I haven’t asked him anything that’s especially probing. I’ve merely enquired how he’s gone about navigating the rocky terrain of his most illustrious role, that of “Man at the Centre of Every Bit of Toxic Discourse of the Last Decade”. He was the freckly, Eton-educated face of the British film industry when he won an Oscar for playing Stephen Hawking in The Theory of Everything, sparking conversations about equal opportunities for actors who aren’t able-bodied, cisgender men of privilege. He’d poke that bear again less than a year later, portraying a trans woman in the regrettable The Danish Girl. And he was leading the Fantastic Beasts franchise at the same time as its creator JK Rowling went public with her views on trans people, which transformed her – over the course of three movies – from beloved children’s author to unbridled agent of chaos.

So, without me hammering the point home too aggressively, how has he dealt with it? Redmayne, dressed in a multicoloured jumper and wearing bright red spectacles, stops talking for an unnervingly long period of time. Four seconds pass. Five. We somehow eke it out to six. “You answer, you trip over, you get quoted, get misquoted,” he sighs. “It’s all par for the course. But the way I explain it to myself is I’m just a f***ing actor.” He lets out a surprisingly booming laugh for a relative wisp of a man. “I wasn’t bred to be a politician, or a great speaker, or a particularly articulate advocate. I will, of course, sputter my way through [advocacy] for the things that I care about... but I’m just an actor.” He laughs again, those icy blue eyes of his catching the light. Then he smiles. He wears the expression of a man never more relieved to reach the end of a thought. I think he’s going to stay in the room.

Redmayne is excellent company: loose, self-deprecating, gregarious. The 42-year-old has a great physical elasticity to him, his limbs in constant motion. He likes to cradle his chin in the palm of his left hand and dart his head from side to side. Often to look out of that window. He went to clown school a few years ago – or, as it’s properly known, Paris’s esteemed École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq – where he learnt to stretch and bend and curl himself into odd shapes. It left him seemingly completely at ease in his own skin. So I feel bad for briefly making him want to crawl out of it.

There’s no clowning in Redmayne’s new project – he left that behind on the stage, where he played the rubbery, eerie Emcee in Cabaret in the West End in 2022, then on Broadway earlier this year. Instead, he’s carrying a very big gun and wearing enviably plush suits. A new adaptation of Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel The Day of the Jackal, which arrives on Sky and Now next Thursday, casts him as an immaculately tailored assassin-for-hire: the Jackal of the title, immortalised on film first in 1973 by Edward Fox, then in 1997 by Bruce Willis. This TV reboot transposes the story into a modern setting, with the Jackal ordered to take out tech gurus and CEOs while disguising himself using cutting-edge makeup and prosthetics. In pursuit, meanwhile, is a ruthless MI6 agent played by No Time to Die’s Lashana Lynch. What unfolds over 10 tautly plotted episodes is a high-pressure game of cat-and-mouse, with shades of Killing Eve in the pair’s dynamic.

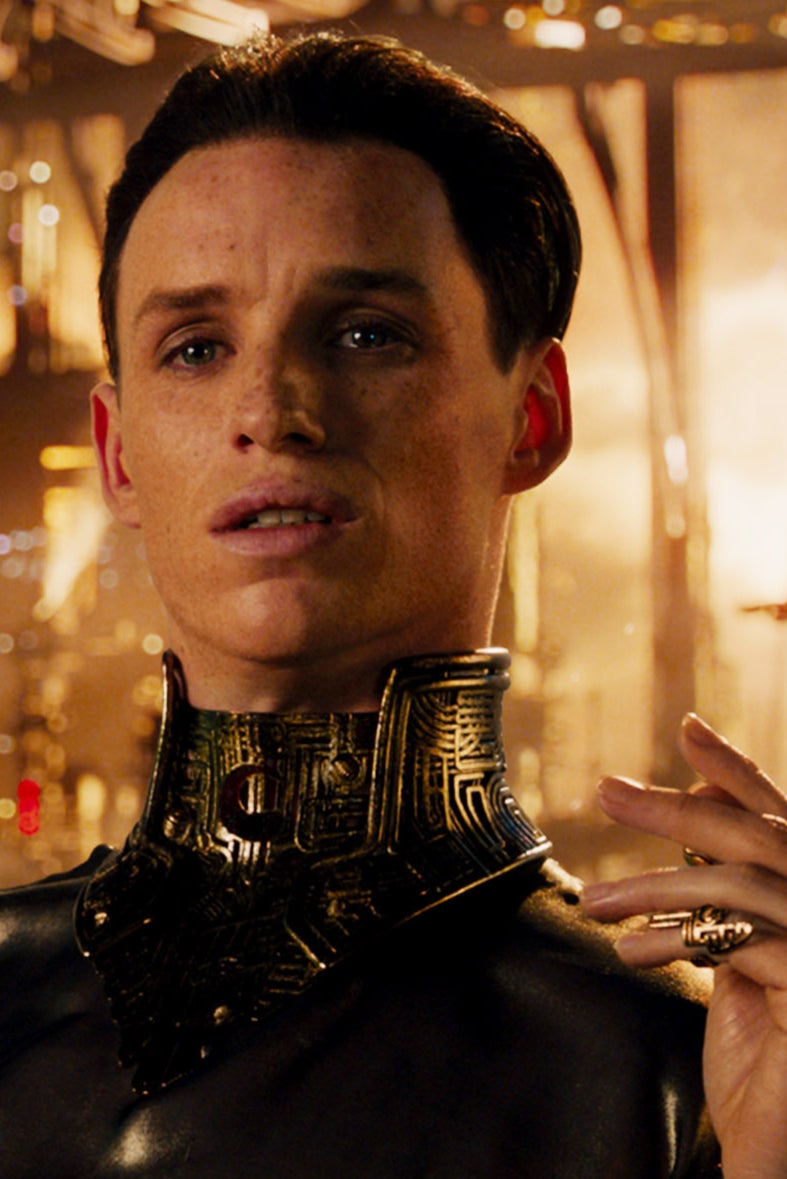

At the audition, I put on my best ‘space emperor with mummy issues’ voice, and that was what came out – it was definitely a big swing

It’s very fun – Ronan Bennett’s scripts are nicely propulsive and twisty – and very pretty. It shot for seven months across Europe, including in Budapest and Croatia. “There have been many years when I’d watch The White Lotus and go, ‘Why do I never get those jobs and hang out on beautiful beaches?’,” Redmayne laughs. “So I wouldn’t want to say that was the reason for taking the job, but it was pretty high up there. I’ve spent years playing Elizabethans and Victorians, or people in the 1920s or 30s. This was the first contemporary thing I think I’ve done in years. And it was nice to be able to just whip on a pair of trousers and a shirt every day, versus lots of 26-piece tweed suits.”

Redmayne grew up watching the 1973 adaptation with his family, so was apprehensive at first when he was approached for the revival. “You don’t want to butcher things that you’ve been obsessed with,” he says. But as he read each of Bennett’s scripts, he found himself won over – 10 hours with the Jackal, rather than just two, allowed for a real character to shine through. “Edward Fox had this astonishing charisma, and could remain deeply enigmatic but deeply compelling,” he says. “But over 10 hours you can get inside that person.” Here, that means introducing the Jackal’s wife and children, sun-kissed Spaniards with no clue what he does for a living.

The overarching story, too, can be a little more complex. “The original film was quite binary – the Jackal was the baddie, Charles de Gaulle [the Jackal’s target] was the goodie. Here, though, everyone is morally grey. Lashana’s character has these questionable behaviours, too. So you have two people who are obsessive and meticulous, and both extraordinarily compromised.”

He didn’t dig too deep into the world of international assassins while researching the role. “I did quite a lot of weapons prep, but I didn’t delve into the dark web and try to find an expensive assassin,” he deadpans. “I chose to put my efforts elsewhere. But I do think these people exist in some capacity. And I suppose the line between assassination and terrorism is probably quite thin?” He nods his head. “Oh gosh, this interview suddenly got very serious, didn’t it?” Redmayne does this a lot – as if leaping out of the conversation to carefully self-edit in real time, or try to envisage what the finished interview will look like. (That his wife Hannah, with whom he shares two children, previously worked as a publicist may or may not be a coincidence.)

Anyway, Redmayne is perfectly cast in The Day of the Jackal. He replicates the tapered-down opacity of Fox’s performance, while lending the character exciting notes of humour. You like him, even if you probably shouldn’t. For my money, it’s probably the most relaxed and human Redmayne’s ever been on screen; a total inverse of the squirming menace of Cabaret.

Redmayne has described himself in the past as a “Marmite” actor – someone whose mere presence in a project will either tickle your fancy or send you running for the hills. This might be down to his penchant for big swings, though; performances that bend to pomp and theatricality. Think the pouty flamboyance of his star-making turn in 2007’s Savage Grace, alongside Julianne Moore. Or the huffing, gasping vocal derangement of his work in Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s 2015 sci-fi flop Jupiter Ascending. Must a performance, though, always be “good”? Can it not just be so balls-to-the-wall wacky that it becomes practically hypnotic?

“There was a moment in the Jupiter Ascending script that described the character’s voice,” Redmayne explains carefully, as if he’s standing in the dock. “It said that his throat had been ‘gnarled out’, or something like that. So at the audition I put on my best ‘space emperor with mummy issues’ voice, and that was what came out.” The Wachowskis let him keep it for filming. “I had the most wonderful time making that film, but it was definitely a big swing. I do hear that there are people who are into [my performance], which is nice. Though I’m also conscious I have a prize somewhere for giving the worst performance of the year.” He chuckles. (It was Worst Supporting Actor at the 2016 Golden Raspberry Awards, if you’re curious.)

Does he read his own reviews? “Oh, yeah, absolutely,” he replies, without hesitation. He only finds it difficult to read them if he’s in a play, where they can’t help but impact what he’s doing night after night. “TV and film, though, often it’s so long since you did the thing that there’s a level of detachment from it. But the interesting thing about them is that I’d say most actors are harsher critics of themselves than any critic can be. It’s rare that I’m sitting reading a bad review of one of my performances, going, ‘No! They got it wrong!’ I typically sit there going, ‘Oh, yeah, I saw that too.’”

It sounds like a relatively healthy approach to criticism, I suggest. “Oh, none of it’s healthy!” he shoots back. “The whole industry is deeply unhealthy. It’s a horrendous job to do for health reasons.” He giggles again.

I’m curious about his relationship with some of his past work, too. The Danish Girl, for instance, has had an unusual afterlife. While the film – in which Redmayne played Lili Elbe, one of the first known recipients of gender-affirming surgery – earned reasonably strong reviews upon release, and Redmayne a Best Actor Oscar nod, it’s since been generally regarded as Very Very Bad, a relic of a different era in trans representation and films about queer lives. Redmayne has long stated that he probably shouldn’t have starred in it (“I made that film with the best intentions, but I think it was a mistake,” he said in 2021). But does he have pride in the work itself?

“I think that goes back to what I was saying about reviews,” he explains. “I’m certainly more critical of my own work than most critics, I would say. So the reason I do this job is to aspire to those glimmers of something that momentarily feels real.” He rubs his eyes. “It sounds f***ing pretentious, but there are those moments, and sometimes they last for under a second, where you’re completely free, and you’re playing against someone, and everything is alive, and momentarily you go somewhere else.”

How often does he get that feeling? “Perhaps once every five years? And it lasts under two seconds, but it’s addictive. It’s a drug, and the thing you keep aspiring to.” But pride... “Right,” he says. He takes a big pause. “When you watch stuff back, 99 per cent of it is not that moment. I see the foibles and the things that don’t work. And whether something I’ve been in has been criticised or scrutinised because of what it says to the world, that can definitely shift what I think of the story, or how I feel the story should have been told. But that’s separate from whether I have pride in the work, absolutely.” He takes another pause. “That was really convoluted, wasn’t it?”

If Redmayne is very good at a kind of wordy obfuscation, it’s likely because he’s done this for a while now. He was 33 when he won his Oscar for playing Hawking in The Theory of Everything, and had already bounced around Hollywood for nearly a decade before that. He was part of a starry contingent of British actors who went over to Los Angeles around the same time, all of whom seemed to flatshare or at least sleep on each other’s sofas at one point or another: Jamie Dornan, Andrew Garfield, Robert Pattinson, Daredevil’s Charlie Cox.

“We were just a group of dreamers trying to become actors,” he says, proudly. “And we’d all been told that it was an impossible trade – and it is an impossible trade, just as the amount of unemployment is so extreme – so we’re all quite astonished that we’re still here and working. It’s a weird one, though, because in the early days it was profoundly intense, because we were all competing against each other for everything. So these were friendships that were certainly wrestled through, but always with great love and respect.”

Today, he’s massively grateful for them. “It’s so lovely to be navigating such odd terrain yet having pals going through similar things who you can call up. And it evolves, too. Like, how do you negotiate being an actor and being a parent? How do you negotiate deciding whether to go off and do a job for eight months? How do you deal with the press and interrogation?”

Having such famous friends, though, means he’s often expected to pull out anecdotes from their shared history, yet comes up empty. “I wish we’d done more crazy s*** 20 years ago, just so we’d have more things to spew up on the Jimmy Kimmel show,” he laughs. “But the material is running pretty dry at this point.”

As for what’s next, Redmayne is unsure. Fantastic Beasts is “over, as far as I’m concerned”, so his diary is currently open. But he’s excited for the future. “I love variety, and I love pushing myself, and I hope to continue doing that,” he says. “I’ll always take a big swing, and...” He pauses. He turns to look out of that bloody window again. We sit in silence for a few seconds. Three go by. Then four. Redmayne finally swings his head back round to me. “Oh, I wanted to say something really profound!” he enthuses. “Dammit!” he sighs, as if imagining our interview won’t now have a proper ending. “But A for effort!”

It’s the thought that counts.

‘The Day of the Jackal’ begins on Sky Atlantic and Now on 7 November, and can be streamed weekly on Sky Go and Now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments