Doctor Who at 50: the old man and the BBC

On 23 November 1963, a new series made television seem bigger on the inside. Doctor Who had arrived – and teatime viewing would never be the same again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

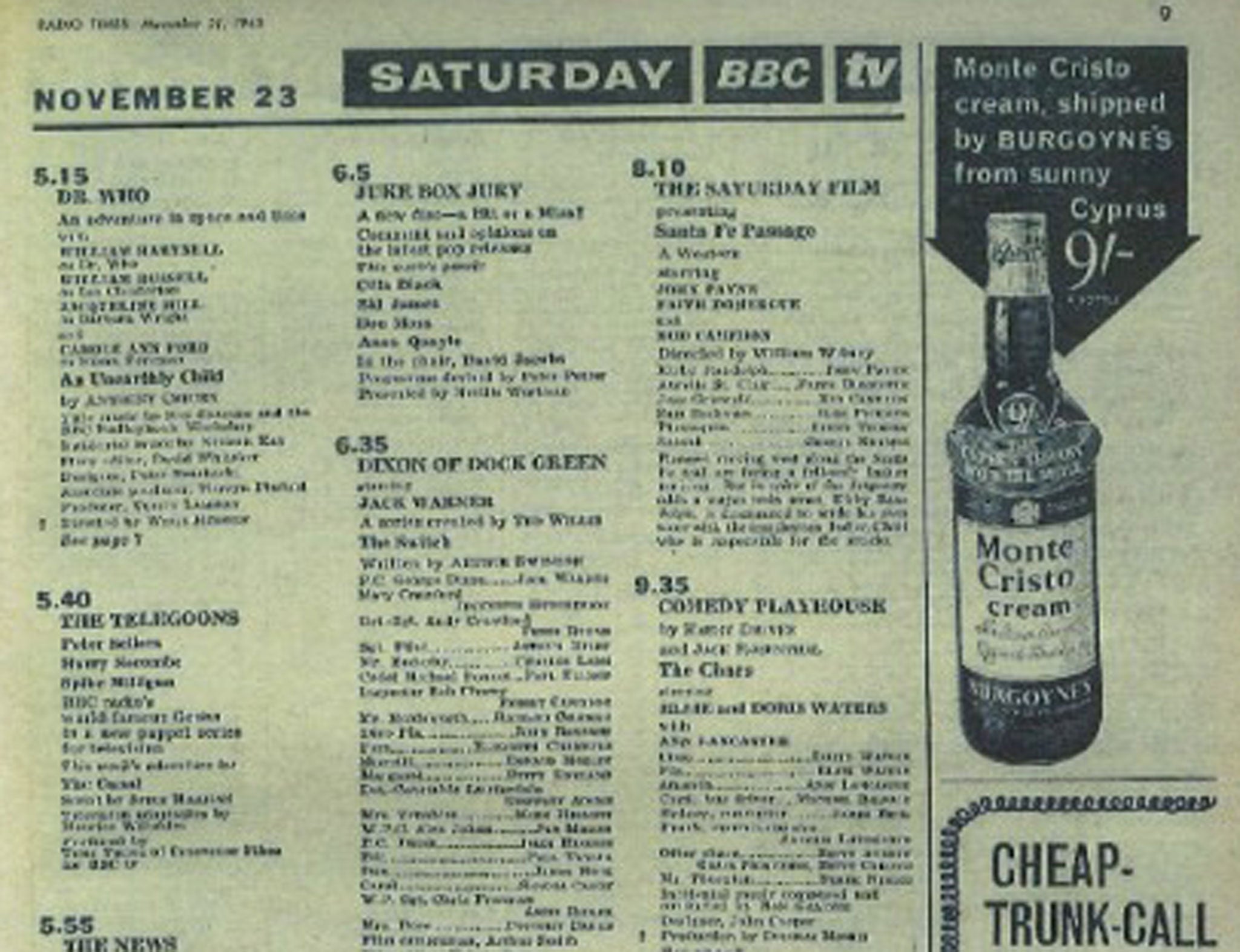

Your support makes all the difference.The BBC schedule for Saturday 23rd November was an eminently predictable one – Juke Box Jury would be followed by Dixon of Dock Green and The Telegoons before the big film, Santa Fe Passage and the latest edition of Comedy Playhouse, “The Chars”, starring Elsie and Doris Waters. The one new departure after Grandstand was “An Unearthly Child”, the first episode of Doctor Who, “A new adventure in time and space” according to the Radio Times. This slot in the schedules was previously occupied by Garry Halliday, the square-jawed pilot who battled with evil smugglers every teatime, but instead of Terence Longdon's manly hero there was an elderly, cankerous eccentric who sported hair of a length that even The Beatles would not adopt until 1966.

Much of the form of the new programme would have been eminently familiar to viewers at that time, a black-and-white drama taped as live in a three-walled studio, but 50 years later it is all too easy to overlook the aspects that made Doctor Who so different in content, both in its choice of protagonist and its music. One of the most startling elements of the new programme to a 1963 television audience would have been the casting of William Hartnell. The 1944 film The Way Ahead had established the actor as the British cinematic NCO par excellence for the next two decades: in Carry On Sergeant (the first in the series) and the ITV sitcom The Army Game, he stood ramrod straight and spoke with an incisive voice, designed to induce terror in anyone found idle on parade.

Hartnell was equally adept at playing commissioned officers, policemen and ruthless spivs, and in Doctor Who he brought the same sense of understated menace that he did to his henchman in Brighton Rock. In his brief appearance in the first episode – he is only on screen for the last few minutes of the programme – Hartnell effortlessly conveys mystery and a genuine sense of unpredictable danger.

These elements of the Doctor's character were perfectly encapsulated by the theme tune. The producer Verity Lambert asked Ron Grainer, composer of the opening music for Maigret and Steptoe and Son, for a tune with a beat that was “familiar yet different”. A single A4 sheet was despatched from Grainer's home in Portugal to the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, where Delia Derbyshire was placed in charge of fully realising Grainer's composition – and, at a time before synthesisers, had to create each new sound from scratch.

The swooping noises on the soundtrack were created by Derbyshire painstakingly adjusting the pitch of an oscillator to a carefully timed pattern, while the rhythmic hissing sounds were the product of filtering white noise. All of these musical effects had to be captured on individual tape recorders.

The result was a theme tune unlike any in the history of BBC Saturday evening television. Just take another look at the line-up of 23 November 1963, where the happening stringbeat sounds of the John Barry Seven's “Hit & Miss” heralded David Jacobs inviting you to join Juke Box Jury and Dixon of Dock Green's theme was “An Ordinary Copper” – music that respectively informs the accessible hipness of Juke Box Jury and the avuncular qualities of PC George Dixon.

But, from the outset, Doctor Who existed in a world apart from the familiar comforts of BBC Light Entertainment. Broadcast in 1953, the first BBC science-fiction series for grown-ups, The Quatermass Experiment, used Holst's “Mars, the Bringer of War” as its theme. But Derbyshire's music for Doctor Who establishes the idea of other worlds co-existing with our own, just as the new programme's eponymous figure has a very alien sense of morality. Unlike the heroes of post-war British science-fiction cinema, Doctor Who does not have a compassionate professor or crusading reporter fighting for the good of mankind, and supported by a be-medaled major commanding a fleet of Austin Champs, but a cantankerous and deeply selfish individual.

The original idea was that the Doctor, assisted by his granddaughter and two English school teachers, would roam through history in an educational way that would appeal to “intelligent 14-year-olds”. When Ian and Barbara become worried that Susan Foreman, their pupil at Coal Hill School, is approximately two centuries ahead of the curriculum – although she still enjoys listening to John Smith and the Common Men on her pocket transistor – they decide to pay a visit to her grandfather, who apparently resides in a junkyard. However, from the moment that Hartnell utters the deeply menacing line, “What is going to happen to you?” when the wonderfully tweedy Ian and Barbara stumble into his lair, it is clear that dependability and paternal wisdom will be in very short supply.

Even the limitations of BBC drama of that time work in the programme's favour. To mock Doctor Who's studio-bound nature is otiose. “An Unearthly Child” was never designed to be broadcast on a vast flat-screen but to be aired on a flickering GEC 14-inch set with the living-room light extinguished. The cramped sets in Ealing Studios establish an air of claustrophobia, which is contrasted with the brightly lit interior of the Tardis. The sense of darkness in the studio exacerbates the sense of encroaching unease and one of our first sights of the Doctor's craft is through the porthole-like windscreen of the teachers' second-hand Wolseley.

Given the programme's limited budget, an attempt at an elaborate spacecraft would have been an exercise in bathos, whereas the use of a familiar artifact was a masterstroke; in Doctor Who, even the most seemingly banal of sights may be inherently dangerous. The idea that a spaceship might be elderly and prone to breakdowns – the original outline for the programme suggested “a recurrent problem is how to find spares” – was a refreshing one to countless Britons who still drove 15-year-old cars and who lived in homes with pre-war furniture.

The ensuing adventure, in which the Tardis travels back to the prehistoric ages only to encounter some irate Equity Card holders clad in prop furs and dubious wigs on a quest for fire, does not date especially well but the tropes that would serve the programme over the next 50 years had already been established. After the closing credits the viewers could gratefully retreat to Sid James, Cilla Black, Don Moss and Anna Quayle giving their considered opinions on this week's discs, to be followed by Jack Warner's salutation of “Evening All”. But Hartnell's performance and Delia Derbyshire's music subverted the predictability of afternoon television by inferring a world outside of the British teatime that did not follow any familiar social codes or mores.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments