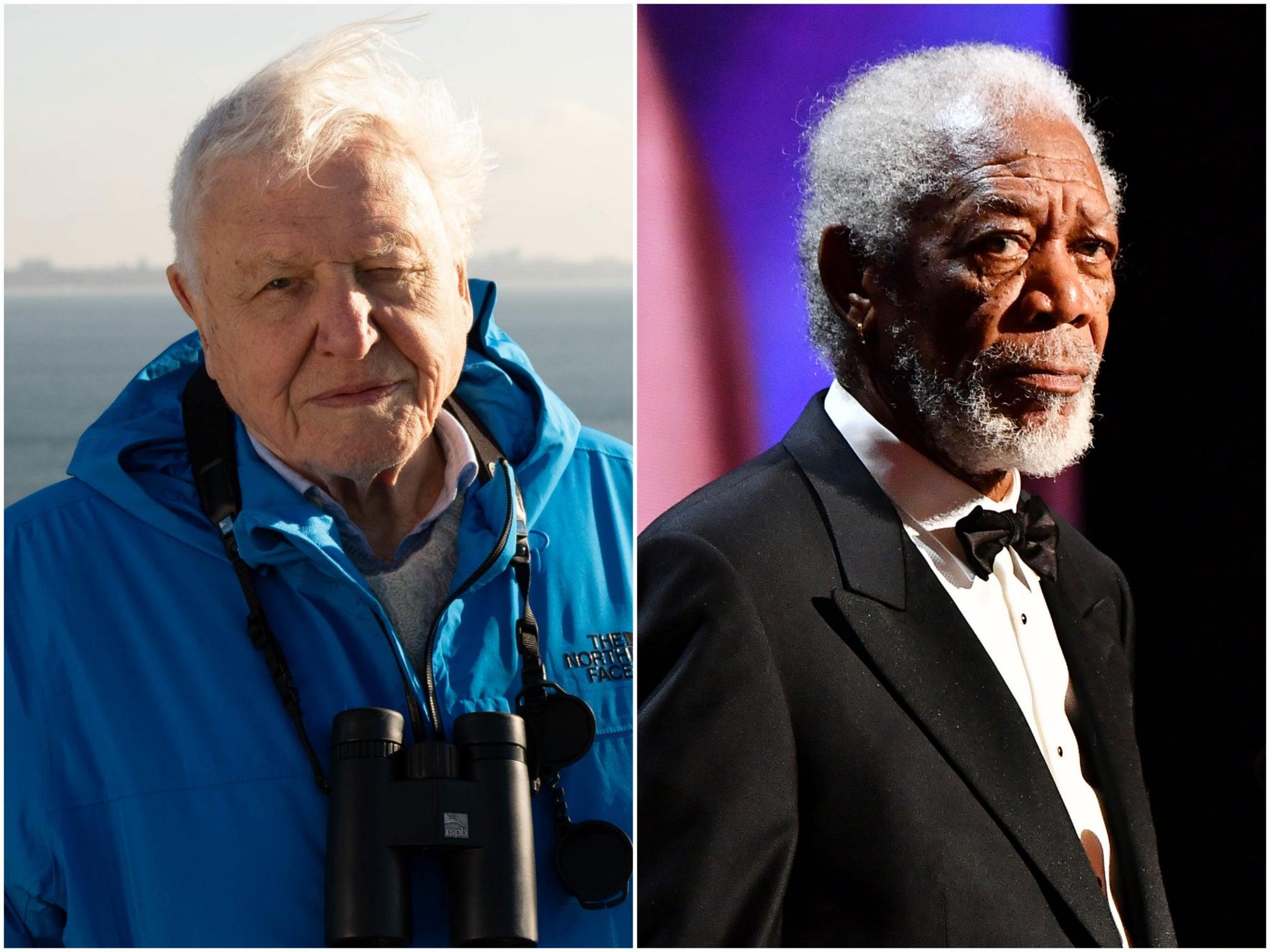

The battle of the behemoths: David Attenborough and Morgan Freeman go head to head with their natural history epics – but who will win?

Attenborough’s BBC One series ‘Planet Earth III’ and Freeman’s Netflix show ‘Life on Our Planet’ are arriving within days of each other, writes Nick Hilton. Although these men are both masters in their field, and as long in the tooth as some of the creatures whose movements they narrate, Freeman can’t hope to replicate the magic of Attenborough and the BBC’s Natural History Unit

David Attenborough and Morgan Freeman walk into a bar. Attenborough turns to Freeman with a quizzical look. “If I’m here,” he says to a baffled Freeman, “and you’re there...” Freeman gasps! “Then who the hell is narrating this joke?!”

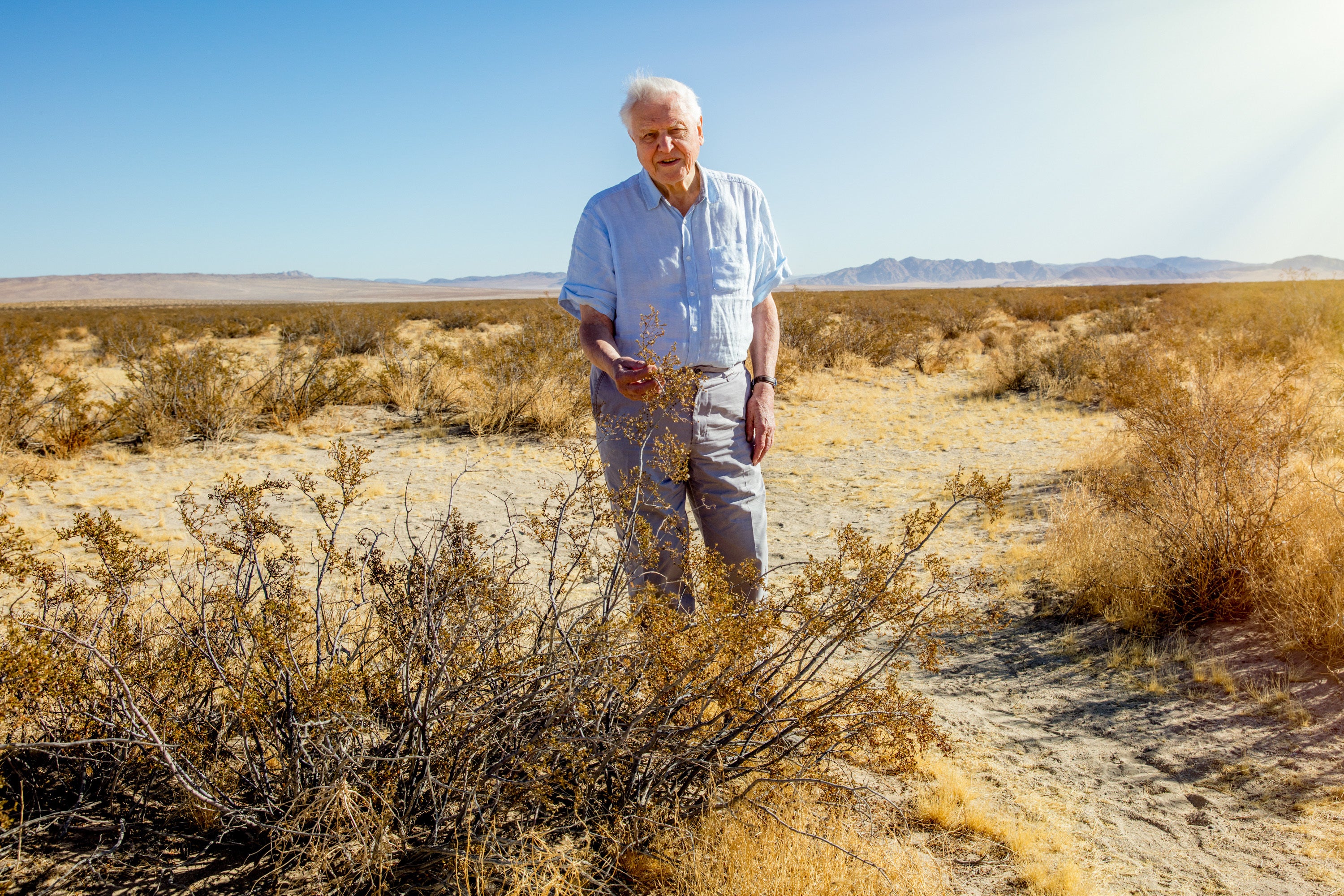

For decades now, the disembodied voices of these two men have dominated screens big and small. Attenborough, who was born just a few weeks after Elizabeth II (they’re both Tauruses, of course) is now aged 97 and returns to BBC One this week with Planet Earth III. A world-renowned behemoth, straddling both science and entertainment, Attenborough has an ability to conjure drama with little more than a whisper. Mother Nature meets Father Time.

Just three days after Planet Earth III hits screens here in the UK, Netflix’s most ambitious project yet – Life on Our Planet – is released across the globe. With Attenborough confined to terrestrial duties, Netflix had to get creative with its voice casting for the story of life’s epic, 4-billion-year journey on Earth. If your biggest rival is an old man, his voice laden with textures of craggy weariness, how do you differentiate yourself? Well, Netflix’s answer is, of course, to hire 86-year-old Oscar winner Morgan Freeman, the definitive American narrator. Where Attenborough’s voice is puckish, Freeman’s is sonorous. Everything he says, however banal, feels laden with meaning. “This is the story of life,” Freeman purrs, while two Smilodon bare their teeth. The prehistoric Smilodon may have gone extinct 10,000 years ago (or, in other words, 103 Attenborough lifetimes ago) but somehow the vast reserves of natural history feel contemporaneous with these elderly voices. After all, both are long in the tooth.

Although, of course, nobody is born an elder statesman. As Planet Earth III reminds viewers, Attenborough has been sailing these same seas and treading these same shores since the early days of public broadcasting. The first episode of this latest series shows a shirtless Attenborough in 1957, feeding a green turtle on a coral cay in the Great Barrier Reef. He is strikingly unrecognisable from the avuncular grandpa the nation now reveres. The oft-repeated factoid that Attenborough is the only person to have won Bafta awards in black and white, colour, hi-def, 3D and 4K resolution is testament both to his longevity and the way that the BBC’s wildlife filmmaking has rapidly, and radically, evolved.

And one of the most pronounced evolutions of recent years has been the emergence of rivals to the BBC’s hegemony in wildlife documentary filmmaking. Netflix, particularly, has spent big on a range of docuseries, including Our Planet, a format devised by Alastair Fothergill and Keith Scholey, the former BBC bods behind Planet Earth, Frozen Planet and The Blue Planet. When looking for a narrator for Our Planet, Netflix plumped for the most reliable voice in the field: David Attenborough.

What is it about this nonagenarian that stops TV executives’ imaginations short? Certainly, it is no longer down to his pedigree as the energetic former host of Zoo Quest, where he’d traipse across the globe and get hands-on with monkeys. Nor can it solely be the well-honed dramatic delivery, which, though distinctive, is easily imitable. Instead, there is something circular about Attenborough’s position. The hundreds of hours of broadcast television Attenborough has narrated make it impossible even to take the train over Blackfriars bridge without that distinctively portentous voice in your head, pronouncing, “The mighty Thames, our link with the natural world...” Put simply: he has become the embodiment of the natural world.

Attempts to find replacements or alternatives – such as Stephen Fry lending his dulcet tones to ITV’s A Year on Planet Earth – have run up against that uncanny sense they are off-brand Attenboroughs. And it has become a rite of passage for A-listers to hit the voice booth. Interested in North American nature? Pick between Barack Obama’s Our Great National Parks on Netflix or Michael B Jordan’s America the Beautiful on Disney+. Like big cats? Try Tom Hardy’s Predators on Sky or John Boyega’s Serengeti on the BBC. All are nice, masculine – always masculine – voices. But neither Creed nor Venom, nor Finn or the 44th president of the United States, can quite match Attenborough for skill of intonation.

But Freeman is no novice in this arena. He narrated the Academy Award-winning March of the Penguins, which was a landmark in the genre. He’s even had a crack at a Netflix gig before: the series Our Universe, which took the lens out as far as possible (and was broadcast to little fanfare). Freeman’s position as the arch-narrator – perhaps best exemplified by his voiceover for the film The Shawshank Redemption – has given him a meme quality. His Southern baritone is a staple of comedians and impressionists, even as it growls increasingly urgent warnings about global warming. “Earth never remains stable for long,” he declares, ominously, in his new series. “Sometimes that helps life, sometimes that hinders it.” What hinders Freeman, however, is Netflix’s failure to replicate the magic of the BBC’s celebrated Natural History Unit. An over-reliance on CGI and anthropomorphism gives Freeman’s narration a sense of airless aphorism. Attenborough, meanwhile, is on sparkling form, breathing voice into subjects ranging from Namibian lions to minuscule sea angels.

Both Planet Earth III and Life on Our Planet have a dominant preoccupation: climate change. These two old men – one scratching 90, the other inching towards his century – have a singularly panoptic view of humanity’s progression. Do these voices, from the twilight years, resonate with a planet also in its final act?

There has been no confirmation as to whether Planet Earth III brings the trilogy to its conclusion, or whether it affords Attenborough a chance to hang up his vocal cords (if that’s not too visceral a metaphor). The BBC has no replacement ready, despite attempts to cultivate blokes like Brian Cox or Gordon Buchanan as heirs apparent. As the seas rise and the forests burn, it’s fitting, perhaps, that the broadcasters too appear to have no plan B. They remind us that life on our planet, Earth, is not a permanent fixture either.

‘Planet Earth III’ arrives on BBC One at 6.15pm on Sunday 22 October. ‘Life on Our Planet’ is out on Netflix on Wednesday 25 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments