CSI Cyber: The Channel 5 show focuses on hacking but is it too kind to cops?

Lauren Walker analyses the latest incarnation of the 'CSI' franchise, which comes to Channel 5 next week

More than 20 years ago, DNA forensics appeared to implicate O J Simpson in the stabbing to death of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and a waiter, Ronald Goldman. Despite abundant evidence – a bloody glove, blood drops, hairs, carpet fibres – the prosecution faced a major hurdle in convincing the jury to convict him, in part because jurors lacked an understanding of forensic science. Simpson was acquitted.

In 2000, five years after the trial, a television show called CSI: Crime Scene Investigation was first broadcast in the US (Channel 5 showed it here the following year). Audiences were led under the yellow tape and into the world of forensic science for the first time. Set in Las Vegas, each episode began with the discovery of a body and followed a team of investigators collecting and analysing evidence, questioning witnesses and catching bad guys.

The show's overwhelming popularity led to two spin-offs: CSI: Miami in 2002 and CSI: New York in 2004. By 2007, the CSI franchise had become a global cultural phenomenon (CSI: Miami was named the world's most popular television show in a study of ratings in 20 countries in 2006); it had not only beaten the competition in viewership but had successfully injected a new vocabulary and grasp of forensic science into the public consciousness.

In 2010, the creators began brainstorming a fresh iteration that would both venture into unchartered “edutainment” territory and attract huge audiences. Their zeitgeisty creation, CSI: Cyber, makes its British debut next week on Channel 5. It follows FBI cyber crime division investigators led by cyber psychologist Avery Ryan (Patricia Arquette). The team works on the edges of the darknet, the anonymous side of the internet, solving crimes that “start in the mind, live online, and play out in the real world”, according to the unofficial tagline.

“Our core CSI viewer will see a level of familiarity... that will comfort them,” says Anthony Zuiker, the creator and executive producer of the CSI behemoth. Sitting with him at CBS's Studio City in Los Angeles is Pam Veasy, a CSI veteran of more than a decade. She explains that, while we are undeniably in a digital age, society's understanding of this technology is lagging, and CSI is here to help. “I want people to want to educate themselves,” she says. “From a fax to a computer… to signals sent over towers, the [criminal] possibilities are endless.”

But not everyone felt that the type of education the original CSI provided was a force for good. During the franchise's zenith, critics claimed that the series' exaggerated portrayal of forensic science caused jurors to place undue weight on forensic evidence. Dubbed “the CSI effect”, this phenomenon became increasingly worrisome as scientists began criticising forensic specialities as junk science.

Something similar could go wrong with CSI: Cyber. For a start, cyber psychologist Ryan, who profiles both cyber criminals and their victims on the show, oversees a pretty unrealistic team. One of the characters is hacker Brody Nelson; the backstory is that upon his arrest for wiring half a billion dollars to his bank account, Nelson was given the choice of using his skills to help the agency or going to prison.He is joined by another reformed cyber criminal, Raven Ramirez, who serves as the team's resident social media and cyber trends specialist. These turned-good tech whizzes are accompanied by another hacker, who has always worked for the government, Daniel Krumitz.

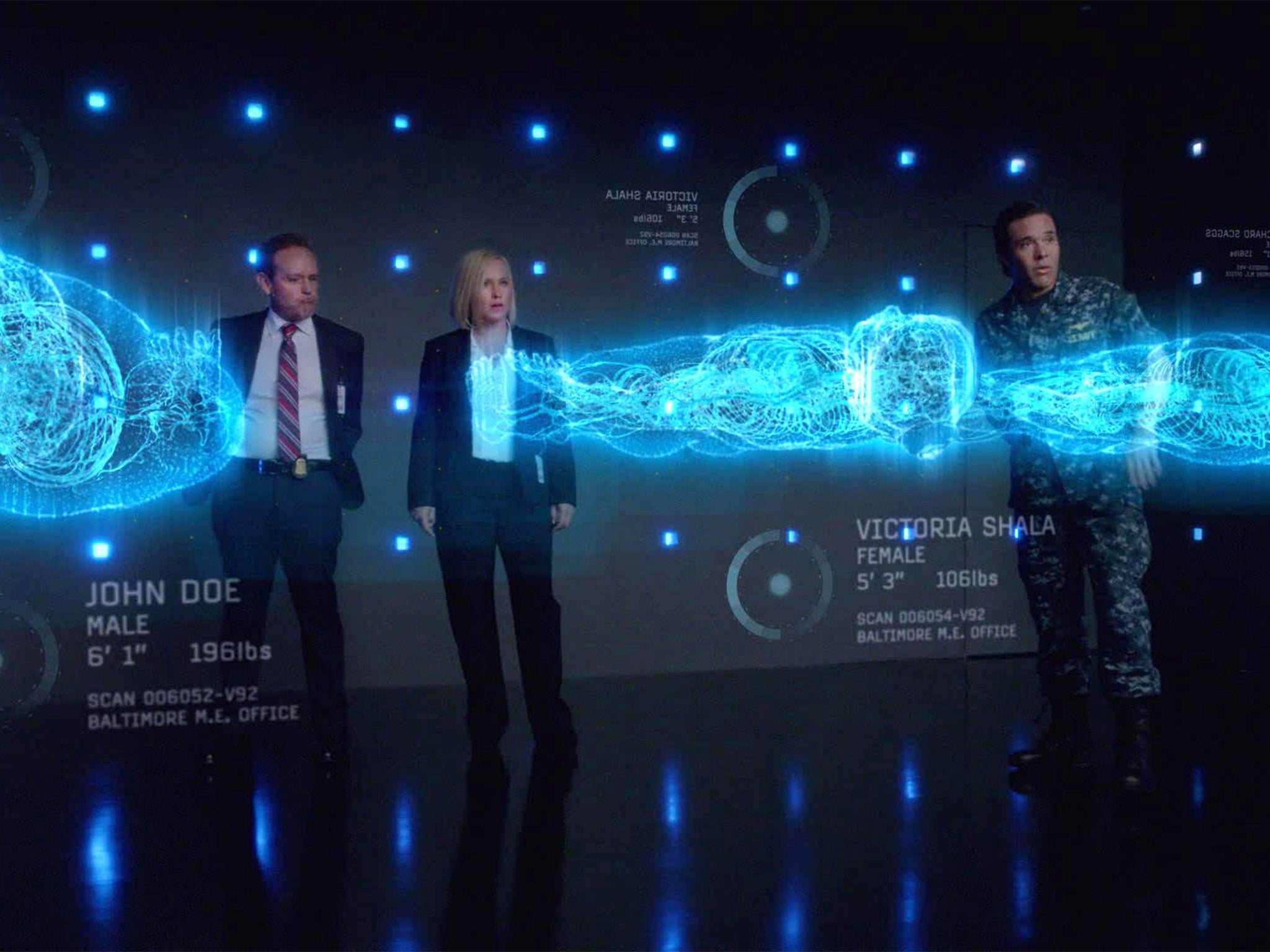

A real-world problem: not only does law enforcement not employ criminal hackers but the show's depiction of what they do is not tethered to reality. Hacking is a pretty boring thing to watch. It involves days or even weeks hunkered over a computer staring at lines of code. Detecting breaches is no easy feat. But in CSI: Cyber, lines of text are colour coded: good code appears in green, malware in red, allowing the team to manoeuvre through computer systems in seconds.

Zuiker calls it the cyber equivalent to when CSI: Cyber's predecessors would follow a flying bullet into a body, tracing back the steps of how it happened. “We have a whole new version of that in terms of how we go inside computers,” he says. “Four people staring at a screen for 47½ minutes is not compelling television,” adds James Van Der Beek, “which is where I come in.” Van Der Beek plays FBI agent Elijah Mundo, a former military man who chases the criminals.

Another of the show's shortcomings is that it has a bias towards the US government. Ryan's character is inspired by the work of real-life cyber psychologist Mary Aiken, who is also the show's main adviser. Aiken knows first hand how today's digital tools can be exploited by criminals in the darknet. Though reports have uncovered mounting instances of law enforcement circumventing warrants to conduct digital searches, Aiken says that on the show the FBI agents “always have to get a warrant... if they want to engage in surveillance”. Representing investigators as the unequivocal “good guys” is also reflected in the fact that the creators have no intention of delving into issues that expose government wrongdoing. “We are not here to make political statements,” Zuiker says.

However, the show's other lead adviser, James Aquilina, also has deep ties with the US government. In his current position as a member of the executive management team at Stroz Friedberg, a global digital risk management company, Aquilina supervises digital investigative assignments for multiple entities, including government agencies. He also helped establish and run the legal section of the FBI's emergency operations centre following the 9/11 attacks.

When preparing for his role, says (Shad Moss, who plays Brody Nelson, “I didn't speak to one hacker, actually.” But what a hacker might have told Moss is that forces working against official interests are not necessarily the bad guys. Throughout the show's creation, advisers partial to law enforcement were the ones asked for guidance in portraying cyber criminals, moulding what constitutes a crime and reflecting how cyber crime is investigated and prosecuted. This message will inevitably affect the public's understanding.

For instance, characters on the show often refer ominously to the “dark web” without fully explaining what it is. This leads the viewer to believe it's a sinister place. But Tor, the common software used for anonymous communication in this part of the internet, was actually created by the US Navy. To suggest that those lurking in its shadows are the primary threat bolsters the government's claim of benevolence.

Just weeks ago, a jury convicted Ross Ulbricht of being the mastermind behind Silk Road, the notorious darknet drug market. The FBI used what some consider questionable investigative tactics to catch him, including breaking into a secure internet browser without a warrant.

As the Silk Road trial began, it was clear that the jury's technological knowledge-gap would be exploited by prosecutors. In opening statements, they referred to the Tor-hidden market as “a dark and secret part of the internet,” while the defence said it could be used for “legitimate means”. And Ulbricht repeatedly said that Silk Road was his attempt to create a truly free and open marketplace. He was found guilty of seven charges and faces at least 30 years in prison.

“In 15 years everyone will know what malicious script is and never to click on a pop-up that says to update your software,” Van Der Beek says. But if CSI: Cyber also makes it easier for the NSA and other agencies to drill down further into civilian life, will it have been worth it?

©Newsweek

CSI: Cyber, Channel 5, 6 October, 10pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks