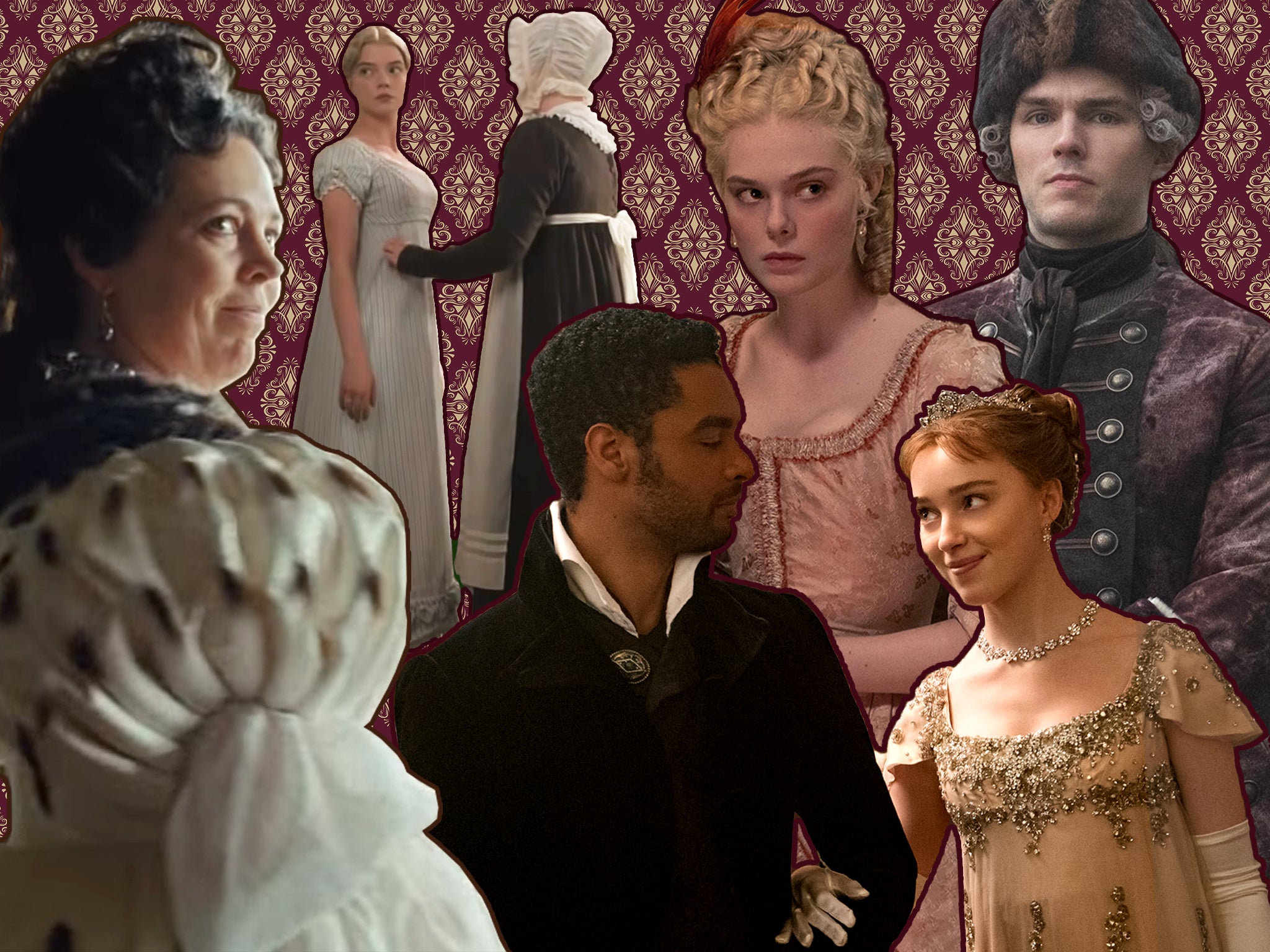

Beyond bodice rippers: How the period drama got with the times

Historical dramas are more modern than ever before, with shows and films from Bridgerton to Emma tackling contemporary themes beneath the bonnets. Isobel Lewis speaks to their creators to find out why they’re mixing it up

Period dramas have long been at the heart of the UK screen industries, from Dickens film adaptations to Sunday night ITV series. In recent years, however, a subgenre of period drama has appeared that is less obsessed with being a historically accurate reflection of the time period and more about bringing together the old and the new. That’s not to say this has never been done before – think 1988’s Dangerous Liaisons with its contemporary plot or TV comedy Blackadder and its current language and humour. But these days, more and more bodice-rippers seem to finally chime with modern times.

In many ways, it’s not surprising. The Regency era as we know it has been defined by the period dramas of the 1990s and early 2000s, where clothes were uncomfortable, language among the upper classes formal and marrying to have children deemed a woman’s only purpose. Adaptations were, for the most part, fairly faithful. But this new breed, such as the forthcoming Bridgerton on Netflix, layer recognisably traditional elements such as costume and set design with modern details, allowing the creators to say something about the past and the present at the same time.

“There’s nothing more rock’n’roll than a restrained time period because it’s more exciting to imagine someone breaking the rules when the rules are tighter,” says director Autumn de Wilde down the line from her Los Angeles home. She had often looked to the 19th century for inspiration in her work as a music photographer and wanted to bring this energy to her 2020 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma starring Anya Taylor-Joy and Johnny Flynn. While Austen’s work has been put on the screen umpteen times before, there’s a lighter, more playful tone to this version of Emma that finds new meaning in the author’s words. De Wilde describes writing “a whole other script” of subtext and what’s left unsaid between Emma’s characters.

“I wanted to make a film that felt like a teen movie, to shine a light on the emotions and remind audiences that the characters are human and that people don’t change that much,” De Wilde says. “Jane Austen was so good at tales of romance and repression of emotions that I think a lot of films choose to oversimplify the rest of it. So rather than trying to explicitly modernise it, I felt like the most modern thing would be to go back to the period, really see the things that were left out and stop trying to make the same movie that was successful in the Eighties and Nineties.”

It would be impossible to talk about this trend and not sing the praises of The Favourite, Yorgos Lanthimos’s 2018 comedy centred around the court of Queen Anne (Olivia Colman) and the two women (Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone) vying for her attention. Compared to Emma, or another novel adaptation bound by dialogue originally written by an author, the film was able to bring together old and new language in a way that complemented Lanthimos’s experimental directing. It was this, arguably, which shocked the audiences, as swearing and pacey dialogue were shoved in sentences alongside antiquated phrasing and the formal court setting of the film.

Screenwriter Tony McNamara was brought onto the project after Lanthimos read his script for a TV pilot about Catherine the Great. This would go on to become The Great, a comedy series in much the same tonal style as The Favourite, starring Elle Fanning and Nicholas Hoult. McNamara tells me that he initially intended to tell the story of Catherine the Great through a traditional dialogue style but found the process uninteresting. “It was the polite period thing I didn’t love, because it felt like backwards looking rather than present,” he says. He says that the dialogue of both projects is “partly a tonal thing, to say to the audience this is a take, this is a view of something. It adds a sort of irreverence, to show that this is a stylised view of all these characters.”

It’s a similar point to one made by Sofia Coppola about her 2006 film Marie Antoinette, which sets 18th-century France to a soundtrack of New Order, Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Cure. “It is not a lesson of history,” she had said. “It is an interpretation documented, but carried by my desire for covering the subject differently.”

Somewhere between De Wilde and McNamara’s approaches, there is Chris Van Dusen, the writer and showrunner behind the big Christmas Day launch Bridgerton. Based on Julia Quinn’s popular series of romance novels, the show follows the wealthy titular family as their eldest daughter Daphne (Phoebe Dynevor) prepares to enter the marriage market at a time when a mysterious, Gossip Girl-esque figure has started producing a pamphlet about the scandals in London. The show is produced by Shonda Rhimes’s production company Shondaland and has everything we’ve come to expect from her: lavish sets, intense relationships and twisty plots.

Van Dusen, who cites the BBC’s 1995 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice as one of his favourite period dramas, had previously written for Shondaland shows Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal and says that he wanted to bring their sense of drama to regency England in Bridgerton. “As much as I love a good period piece, I feel like they’re considered a little traditional, and a little conservative,” he says. The tone of Bridgerton, he continues, is “spirited and daring – people talk fast and there’s a banter there but it’s also really really sexy in a way you don’t always get in a more traditional period show.”

While period dramas have become a genre and huge industry of their own (thanks Downton), these modern takes tend to have more in common with subgenres such as teen romance or absurdist comedy. Viewers tuning into Bridgerton on Christmas Day with their grandma should be warned that this is not Pride and Prejudice but a show where people swear and sexuality is explicitly explored.

What Bridgerton also does is focus on human stories at the heart of the plot, allowing us to realise that there’s an awful lot of similarities between people then and people now. Interestingly, De Wilde cites Ninties teen film Clueless as a key inspiration for Emma, explaining: “[Clueless director] Amy Heckerling really knew Emma and understood how high school it all is, how high school our lives are when we’re in contained environments: school, small town, office buildings.”

McNamara admits to using a similar tactic when it came to creating The Great. The Russian courts of the 18th century felt far away and impenetrable, sure, but how would Catherine behave in a different context? “We’re not trying to make it literal; we’re always going, what is it if it’s not 1780?” he says. “What if she’s a 22-year-old who lives in Hackney who marries the wrong man and wants to kill him? Things are actually often the same, we’re still spinning our wheels in the same way because human beings are very similar and their problems weren’t that different to our everyday problems.”

We have this sense again in the world of Bridgerton, where the women in their empire-waist gowns and the men in their waistcoats are still ultimately young people, barely out of their teens, with desires and needs. The rules and expectations of the world feel old fashioned but the emotions – love, jealousy, passion – are all recognisable. “Underneath all the glamour and the lavishness,” Van Dusen says, “we have this running commentary about how in the last 200 years everything has changed but nothing has changed.”

There’s a growing feminist undercurrent that runs throughout these films and shows, too. As modern viewers, it’s hard to look back on our patriarchal society uncritically, but today’s period dramas often manage to interweave characters who are critical themselves of the way these systems rule their lives. In Bridgerton, we have characters like Eloise (Claudia Jessie) who have no interest in marrying and the show’s lead Daphne, who struggles with her lack of autonomy, telling her brother in frustration: “You think that just because I’m a woman I’m incapable of making my own choices.” But we also meet men struggling with expectations of leading a family or emulating their fathers.

When it comes to The Favourite and The Great, even telling these stories is a feminist act. History has traditionally been led by and told by men, meaning that women who did get into power, such as Queen Anne and Catherine the Great, are less known. For a writer, these characters provide a lot more room to play with language and ideas and push boundaries, because the expectations we have around these characters are less clearly defined.

McNamara says his inspiration to write about Catherine the Great in the first place came from an urban legend that she died after trying to have sex with horse, a story he describes as an act of “political assassination, because she was a woman and was unapologetic with her sexuality”. But if all audiences know is the horse story, there’s room to have fun and less need to be strictly held by the truth. The Great has been described by Hulu as “anti-historical”, with McNamara believing that accuracy is far less important than entertainment value. “If you’re a slave to the detail it destroys the drama and eats away at the essence, so I stripped all that out to make the women’s stories very central and get to that core kernel of truth,” he says.

But while period dramas have often – even unconsciously – acknowledged issues of gender, they have often fallen short when it comes to race. In the dramas of the previous decades, an all-white cast was standard, but in recent years directors and production teams have sought to diversify their pool of actors. This has been met with some backlash from right-wing commentators, but as McNamara points out, as long as we look to the past for our stories, non-white actors will be kept out unless we actively decide to cast them. That’s how there’s been works like Hamilton, Jodie Turner-Smith’s recent casting in a Channel 5 drama about Anne Boleyn or Dev Patel in Armando Iannucci film The Personal History of David Copperfield and 2021’s The Green Knight.

“[The Great] is a modern show that is a take on history and any show that reflects the world has to have a diverse cast,” says McNamara. “I came up in the theatre and am aware of the difficulty diverse actors, great diverse actors, can have in getting into certain types of shows or films. It’s great to be able to cast someone like [Doctor Who actor] Sacha Dhawan who’s an excellent actor but wouldn’t usually get to go up for many period things.”

Bridgerton’s diverse cast has also been at the heart of conversations about the show. Having a black actor like Rege-Jean Page play the Duke of Hastings, the show’s romantic lead, wouldn’t feel surprising in another Shondaland series, but in Bridgerton it feels exciting and progressive. However, Van Dusen is keen to insist that they didn’t take a “colourblind” approach to casting and that the world of Bridgerton is not a post-race society. “Saying the show is colourblind implies that colour and race isn’t considered and I don’t think that’s true for Bridgerton,” he tells me. “Colour and race are as much a part of the show and part of the conversation around the show as class and gender and sexuality are.”

And, of course, as McNamara points out, these times weren’t necessarily as “lily-white” as they’ve always been depicted on screen. Van Dusen says that the show was influenced by a theory supported by some historians that Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuvel), who rules over the show’s court, was mixed-race, with her casting influencing other actors in Bridgerton.

“That idea really resonated with me because it made me wonder what could that really look like and what could Queen Charlotte have done?” he ponders. “Could she have used her power to elevate other people of colour in society, could she have given them lands and titles and dukedoms? That’s really where our particular Duke of Hastings, Simon, came to be.” McNamara is in agreement, adding: “I think the courts of these countries were not as undiverse as people think they were. They just were a lot more diverse than the paintings of the time, you know. Russia was a very diverse country and it’s bordered by Asia and Ottomans and it’s got Siberia so it was a diverse place.”

If you’re looking to these new breed of period dramas for a historically accurate retelling of the past, then chances are you’ll be disappointed. But incorporating modern elements into these stories allows us to think about the past as a living, breathing thing rather than stuffy and separate. After all, confirms McNamara, “you can tell a story that’s got some truth to it about the past and have it be a story about now at the same time”.

Bridgerton comes to Netflix on 25 December.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks