The dark world of Nineties boybands: ‘They put a bucket by the stage so I could spew’

Screaming girls. Sudden riches. Your face on the cover of Smash Hits magazine. Life in a Nineties boyband sounds like a dream, but one survivor of the maelstrom likens it more to being in the military. Jessie Thompson goes behind the scenes of revealing new BBC documentary ‘Boybands Forever’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Nancy Mitford’s 1949 novel Love in a Cold Climate, narrator Fanny admits that “ever since I could remember, some delicious image had been enshrined in my heart, last thought at night, first thought in the morning”. She makes a list – long, various and ever-changing – comprised of the dashing men who have been the subject of her girlish fantasies, including Lord Byron, Napoleon and “the guard on the 4.45”. And wasn’t it ever thus? For me, between the years 2001 and 2002, the image was of Lee Ryan from Blue.

During the Nineties and early Noughties, there were millions of girls like me, lying prostrate with longing as they dreamed of their own personal pop prince. As new BBC Two documentary series Boybands Forever illustrates, these infatuations were literally like a fever; intense, all-consuming and sometimes prone to cause fainting. Fans were not simply fans – “You’re in a relationship with your favourite member,” explains presenter Jayne Middlemiss.

The show finished production in the summer, months before Liam Payne’s death, but now feels eerily timed (although One Direction – the biggest boyband phenomenon of the 21st century – are not mentioned). “Obviously there are going to be parts of it that will feel more poignant and loaded in light of what’s happened,” says Nancy Strang, an executive producer of the documentary alongside her husband Louis Theroux. Perhaps unexpectedly, the pair were inspired to make Boybands Forever by their hit 2021 series Gods of Snooker, which captured the 1980s craze for men in waistcoats who could hit a cueball.

Just like that show, this “was an opportunity to enter a whole precinct full of amazing characters and talent, that also tells you something bigger about the culture of that age”, Strang tells me. For many, “there’s a huge gift of nostalgia”, but there’s also “the audience who don’t know, and are fascinated by the pre-social media, pre-internet age, and what things were like then”.

To my eternal devastation – but perhaps in the interests of my basic dignity – Ryan does not appear in the documentary and thus was not available for interview. (Unfortunately, in recent years, he seems to have lost his way.) But where I had Blue, others had Take That – so adored that a Samaritans helpline had to set up when they split – edgy pop boys East 17, key-change maestros Westlife, or hard-as-their-hair-gel lad squad Five. But everything else was pretty similar: the worn-out cassette tapes and the sheer potency of the emerging feelings you projected onto the poster on your bedroom wall, its subject a safe, far-away figure who occupied a fantasy space in your head. When I was taken to see Blue perform in a seaside town near where I grew up, the experience underwhelmed me; these distant human specks on a stage couldn’t compete with the dreamboats in my head.

Except… these beautiful dreamboats were not imaginary characters; they were real people, and often only teenagers themselves. And, as Boybands Forever shows us, many of them still bear the scars from their time in the maelstrom. They were overworked and overwhelmed, often in a permanent state of discombobulation. Ritchie Neville, a member of Five who appears in the series, describes the extremes. “You’re flying high, doing something that is everybody’s dream. Yet it’s also one of the most stressful, lonely and unhappy times of your life,” he tells me. He remembers being made to go on stage and perform in the throes of severe food poisoning, despite his protestations. “They were like, ‘Nah, the label aren’t having it, you’ve got to go – just go on, do it, come off. We’ll have a bucket at the side of the stage in case you need to spew.”

Neither glamorous nor frivolous was the Nineties pop star life. We see a young, spaced-out Gary Barlow say to himself, “Please, nobody touch me for five minutes, I just want to be.” Mark Owen laments that he can no longer go home, his private address besieged by fans. Diminutive trio 911 found themselves so drained that they couldn’t even celebrate their first No 1 record, while Brian McFadden of Westlife talks of having only five days off a year and missing family members’ funerals.

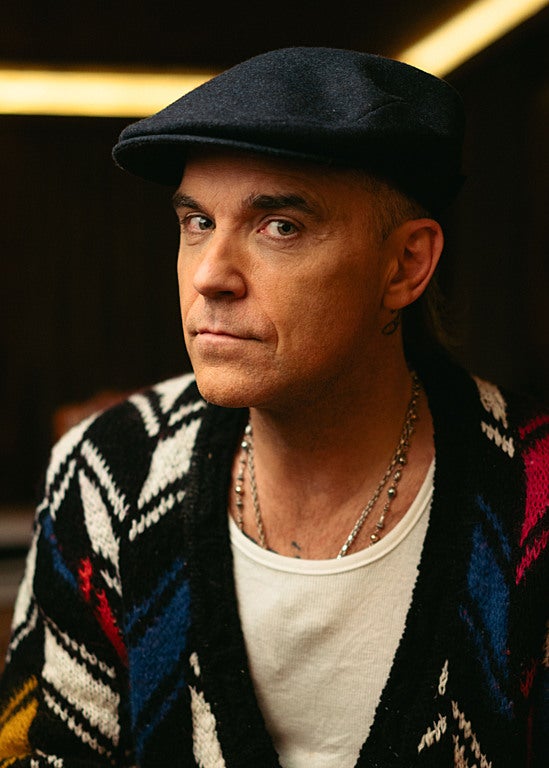

The interviews in Boybands Forever often feel like therapy sessions, and there’s a sense many of the protagonists have only just started to process these experiences properly. Robbie Williams, who hit even giddier heights as a solo star after leaving Take That, recently began to unpack it all in a Netflix documentary. He’s back here, offering the perfect description for the surreal, isolating, almost horror film-like quality of being in a boyband: “It’s the opposite of breaking the fourth wall – it’s going back through and inhabiting this strange place that wasn’t what you thought it was.”

The show explores other dynamics that were depressingly normal at the time: the fact that Boyzone’s Stephen Gately and Blue’s Duncan James kept their sexuality a secret, or that Black boyband Damage were told they couldn’t be on the cover of Smash Hits magazine as no one would buy copies. Eventually, they got their turn – but only by making their image as saccharine and unthreatening as possible.

They went from being at home with mum to suddenly being in this world with that level of fame

We’ve recently been in a period of reflection regarding how female stars were treated in the tabloid culture of the Nineties and Noughties, but there was something particular about being a young male celebrity. “I’m a mother to three boys, one is 16, and I see how young they are still, and there’s a different vulnerability there. They’ve got different ways of connecting and emotionally communicating,” says Strang. Plus, many boybanders were from working-class backgrounds, experiencing fame overnight. “They went from being at home with mum to suddenly being in this world with that level of fame.”

Many were not equipped to handle it. Where today’s stars, from Lewis Capaldi to Sam Fender, are vocal about their mental health, back then it was not a consideration. Some of the most harrowing stories in Boybands Forever come courtesy of Five: Scott Robinson begging to leave the band but being told he couldn’t; Neville arrested for fighting, no longer caring if his behaviour hurt the prize asset that was the band (in the event Simon Cowell called him up and congratulated him on the free publicity); Sean Conlon having a breakdown backstage at the Brit Awards. No wonder Neville says that, when the band ended, he simply thought to himself: “The nightmare will be over, the prison sentence will be over.”

“I’ve been asked a lot of times, ‘Aren’t you angry about it?’ And I was for a while,” he says. “There were moments where I’d just sit obsessing about things, and wasn’t in a good frame of mind for many years. It actually took a lot of my life, not just the time I was doing it, but at least a decade afterwards. It took that just for me trying to make peace with it, come to terms with it, move on from it.”

Chris Herbert, who put together the Spice Girls, and whose father managed Bros and The Three Degrees, managed Five in their Nineties heyday when he was just 25 himself. Today, he sits in front of a wall of gold and platinum records – “There’s a few Five ones there, a couple of Hear’Say ones, and a load more down in the basement” – and I ask how he remembers it all. “A lot of good times, a lot of… pressure, you know,” he says. This was a “brutal” time, when the pressure for bands to have No 1 records was “immense”.

It was with Five that Herbert learned the ropes, working alongside Cowell, who he calls “an incredible mentor”. “We had a lot of laughter, a lot of tears,” he says. “I rode the undulations with the band – when they were having a bad time I took a lot of that on my shoulders myself.” When he looks back, he has one frustration: “The band ended before we really cracked America, and I honestly think we could have done that.”

He concedes things would now be done very differently: regular time off, flying out friends and family, “all those mechanisms to help sustain them and the life of the band”, he says. “More could have been done, and would be done today, on the emotional and mental health side of things, and physical burnout.”

I’m not just talking working a bit hard. I’m talking like ridiculous hours. Ridiculous. Nobody works that hard

It would have to be. Neville, even now, aged 45 and Zooming from a holiday, sounds haunted by the group’s punishing schedule. “I’m not just talking working a bit hard. I’m talking like ridiculous hours. Ridiculous. Nobody works that hard,” he says. “The one that springs to mind is like, the military that are working in a war zone. They don’t have any time, it’s constant red alert. I’d liken it to that.” He thinks bands should now have a counsellor or psychologist available, someone “you can have an absolute off-the-record conversation with, it goes no further – someone who has no vested interest other than your wellbeing”.

The fact many were discouraged from having girlfriends, to avoid upsetting fans and enhance their sense of availability, can’t have helped. Those who did have a personal life quickly realised it wasn’t compatible; after having two children with his then-wife Kerry Katona, McFadden felt he had no choice but to leave Westlife. Neville recalls talking to McFadden about this: “I always thought he was the wayward one, and he’d walked away. He was like, ‘No mate.’ I only understood that being a father.”

Fatherhood has made many of the boybanders reflect differently, thinks Strang. “There’s a paternalistic thing that comes over them, that when they look back and remember, there is almost this inner duty of care to their younger selves.” For Neville, that’s extended to concern for the next generation of young stars. “Or I often see just any 17-year-old and I’ll be like, ‘Bloody hell, they’re kids.’ Knowing that was my age when I went in, I look at them and go, ‘Is that how old I was?’ I felt older – I wasn’t. I was literally a kid.”

Indeed. They were so young. In the documentary, we see a teenage Conlon from Five holding a wodge of notes, marvelling at the amount of money now at his disposal. In 2022, Neville told The Times he became “flat broke very quickly” when the band ended in 2001, and had to sell his house and car. But Herbert says, “I know that I walked away from it, as did they, very nicely. However, I wasn’t spending like a rock star and typically some of them were. They all owned properties at the ages of 20, 21, sometimes several properties, and had a really nice start in life. So I think they did very well out of it actually, for their tenure.”

After Five split, Neville moved to Australia and opened a restaurant. His experience in the band had made him feel he couldn’t handle life in the creative industries, even though it was his passion. But in 2013, ITV2 series The Big Reunion brought together a number of Nineties bands for a one-off concert, and Five ended up getting back together – well, three of them (Neville says they are no longer in touch with Abz or J).

“It’s come back round to where it’s a pleasure to do, you make people happy, then you go home,” he says. He now has a daughter with Atomic Kitten singer Natasha Hamilton (the couple split in 2016) and can make the band fit around his life. “It’s a lot of weekend work, so it means I can be home for the school run, be a dad, cook tea.” Gigs are attended by kids who have inherited the songs from their parents, or, he jokes, “drunk mothers”. Everyone has a very good time.

And yet still I wonder: will we ever see another great boyband? Or has the phenomenon died out, along with coordinated tank tops and CD signings at HMV? “It was very specific to that time, wasn’t it?” says Strang. “I think because of the way the media worked alongside the music industry then, that sort of Smash Hits magazine, CD:UK morning telly era, it was a moment that probably wouldn’t be replicated now. For good or bad, social media is now where music stars have their own relationship with fans and manage it that way.”

Herbert is more optimistic. “I absolutely think there will be a boy band phenomenon again. Will it look like a Nineties boy band? Probably not. But as long as there are young, adoring girls,” he says, perhaps a bit of hope in his voice, “there will always be a market for a boyband.”

The first episode of ‘Boybands Forever’ airs on BBC Two on Saturday 16 November at 9.15pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments