Boat Story’s shocking opening leans on one of TV’s most irritating clichés

The dark BBC One crime drama opens with a grisly flash-forward. It’s a trope that’s been used to death in recent years – and viewers are starting to see through it, writes Louis Chilton

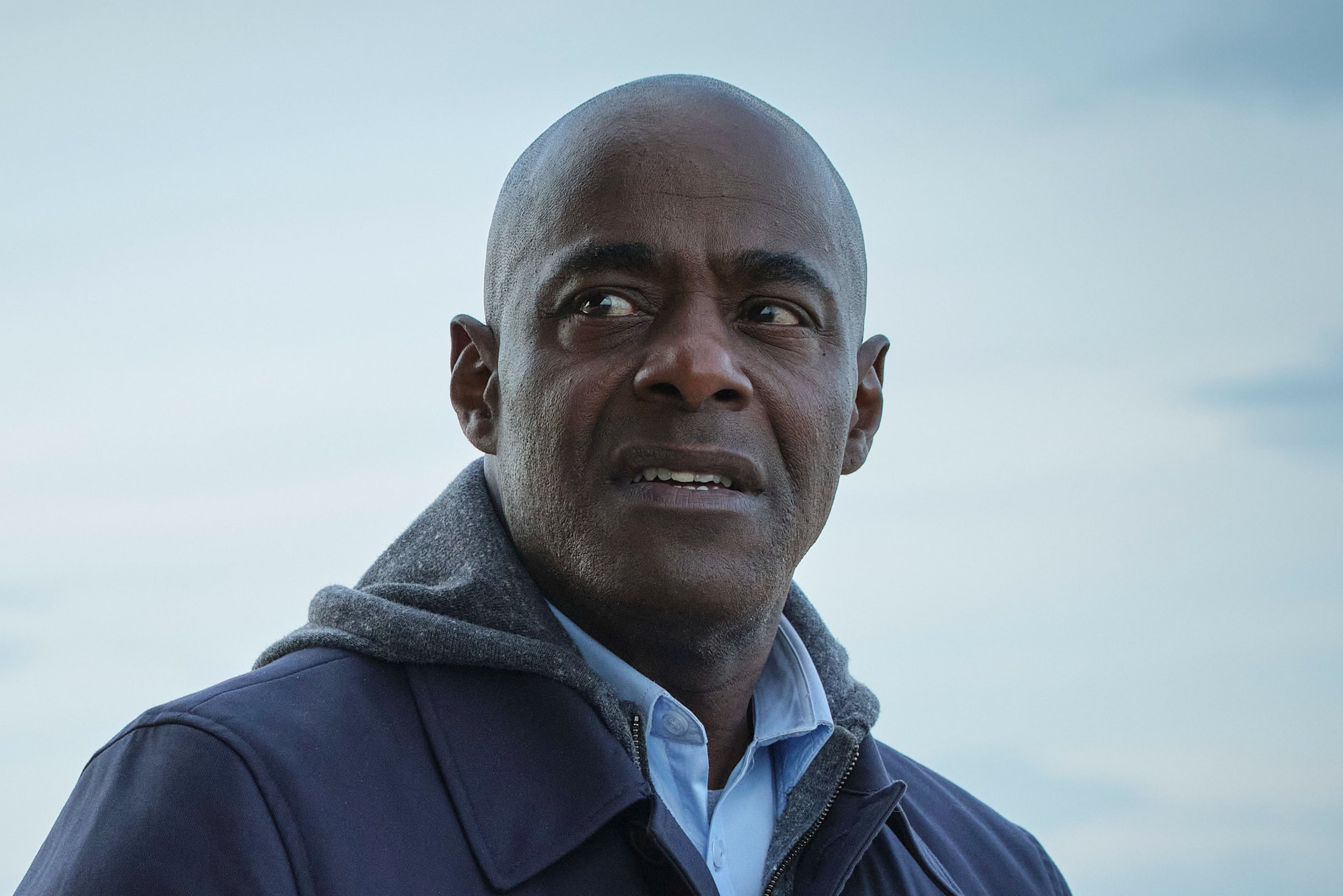

Some prologues use epilogues.” So declares Boat Story, BBC One’s violent new primetime crime drama, in an intertitle card at the start of its first episode. We open in the middle of a vast, desolate field where three children happen upon a grisly find: the decapitated head of Samuel (Paterson Joseph). How did it get there? And why is it detached from his torso? Stay tuned and find out, the series seems to bellow.

From this macabre beginning, Boat Story lurches backwards in time to the start of the story. Samuel – head now enthusiastically conjoined to body – is a solicitor and down-on-his-luck gambler, who, along with maimed ex-factory worker Janet (Daisy Haggard), discovers a boatload of unattended cocaine. The story spirals downward from there, with the involvement of sadistic crimelord “The Tailor” (Tcheky Karyo) throwing another spanner in the works. But always, we know where the story is heading: Samuel’s severed head, left in a field. All roads lead to what Se7en fans know as a “Gwyneth Paltrow haircut”.

Historically, this trope – revealing the violent but mysterious end of a character at the very beginning of a story – has been used to great effect in the past, most famously in Sunset Boulevard, which opens with William Holden’s Joe Gillis face down in a swimming pool. Lawrence of Arabia did it wonderfully. Breaking Bad proved masterful at this kind of foreshadowing, with flash-forward cold opens offering just enough of a glimpse of the future to provoke intrigue, while leaving it so visually abstract as to obscure what was really going on. But all too often, the device has become a cliché – a cheap and lazy way of grabbing the audience’s attention, at the cost of narrative integrity. Recently, it’s been used in everything from Netflix’s The Fall of the House of Usher, to Disney+’s Mike, to the theatrically released Deadpool films, to pick three arbitrary examples.

Patience may be a virtue, but it’s one that viewers are seldom asked to evince. After all, we live in a pop-culture climate where film trailers are often themselves prefaced by rapid, frenetic micro-trailers, a kind of attention-grabbing precis of the two-minute footage reel that follows. Scenes such as the opening of Boat Story serve this same function – advertising the series to viewers, hooking them before they have a chance to swim away. The problem is, this can work to the detriment of the series’ narrative. Because we know the fate of Joseph’s character, there is no tension there; we simply wait for the plot to careen towards a resolution we know is inevitable. The question of what happens is subjugated to the matters of how and why. If a series is sufficiently well-written, then sometimes hows and whys are all you need; Boat Story, often a chore to get through, needs more.

The opening of Boat Story can’t help but evoke perhaps the most famous entry in the niche genre of “kid finds severed body part in field” fiction: David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. The singular 1986 noir begins with Kyle MacLachlan’s innocent teen chancing upon a severed ear while out walking. The mystery of the ear is eventually solved – it’s part of a broader criminal web spun by psychopathic fetishist Dennis Hopper – but it’s never reduced to a simple lure-’em-in gimmick. Even on a gut, aesthetic level, the difference is striking. Lynch’s severed ear, ant-covered and sprouting mold, is a haunting and distinctively upsetting image; Samuel’s head, meanwhile, is limply gore-less. If the purpose is to shock – and it is: what else? – then it seems strange not to commit to the horror of it all.

Boat Story wouldn’t have been radically improved had its prologue been excised. But it’s a case study in the limits of the “flash-forward” trope. Yes, the series knows how to grab your attention. But it has no idea what to do with it after that.

‘Boat Story’ is available to watch now on BBC iPlayer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments