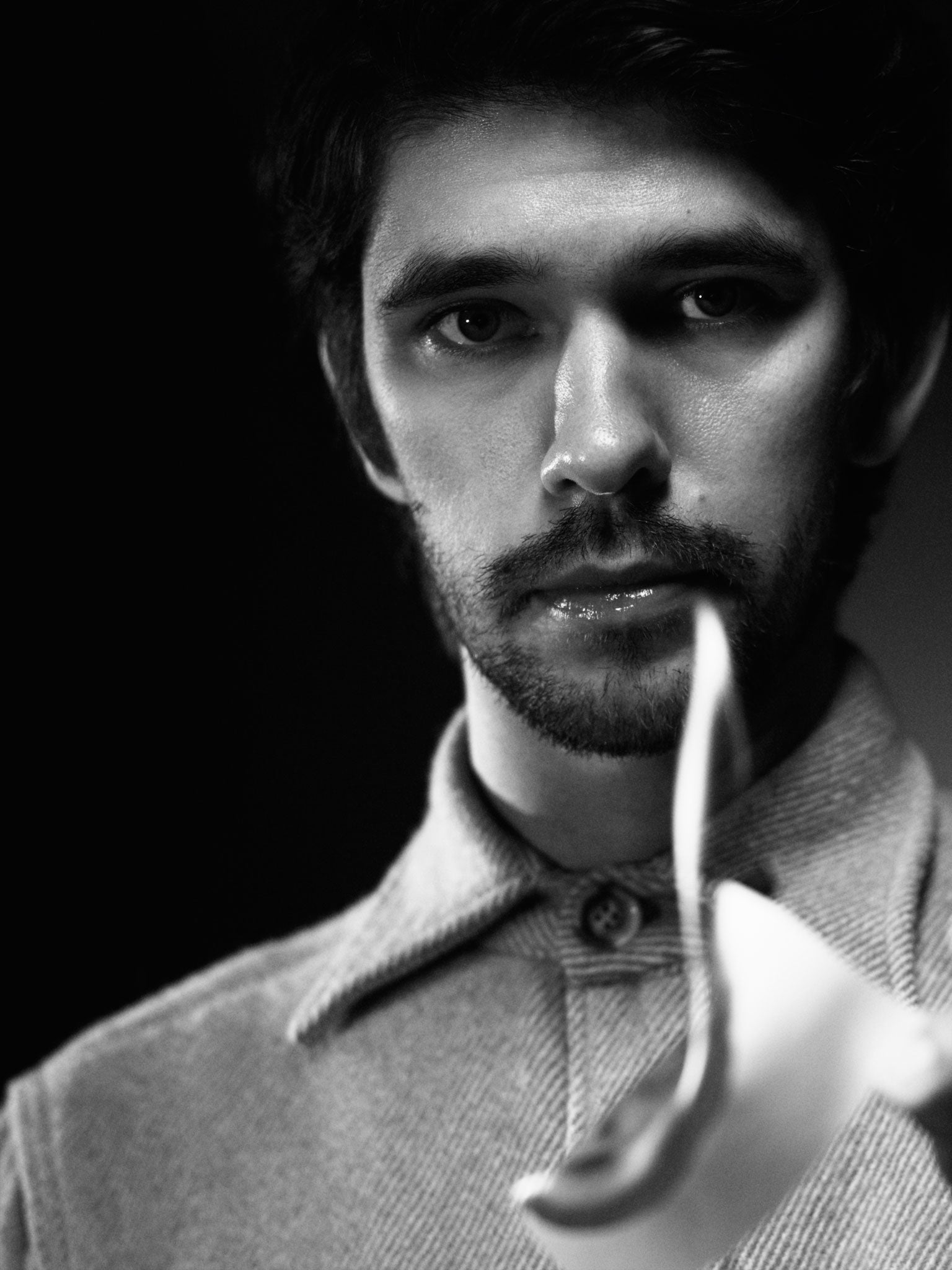

Ben Whishaw: Playing Q in 'Skyfall' was a bit like doing Shakespeare

The Hour actor talks creative discipline, forgetting his lines and dressing up

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ben Whishaw got his big break playing the title role in a Trevor Nunn-directed Hamlet in 2004. The Danish Prince seems a fitting motif for an actor who manages to convey so much of the inner workings of his characters with nuance and suggestion.

Dazzling turns in art-house films Perfume and Bright Star, and his current performances as Q in James Bond blockbuster Skyfall, and as a star reporter in BBC series The Hour, are now being followed by existential epic Cloud Atlas in which he appears alongside Tom Hanks.

Whishaw remains the actor’s actor: intensely private and as outside of the tawdry circus of stardom as his unique talent allows.

Question: You began an art course before moving into acting. Many creative people start a discipline before realising it isn’t right and change course. Some see this as finding the right path for expression; was this the case for you?

Ben Whishaw: I would have loved to have been a painter or a sculptor. I’m still fascinated by those things. At the moment I’m really interested in photography and photographing on film especially. But they are more like little hobbies for me. The thing I love about acting is that you can bring something very personal into the open and at the same time remain hidden because you’re always playing a character in a story that someone else has imagined. You’re always protected. Artists don’t have that; they seem much more exposed to me. I love taking on other people’s words. They are much more interesting to me than my own.

Q: Has working as an actor now spoiled watching films and drama for you, as is often the case when working in an industry that you love?

BW: In a way, yes. I think that you have to be like a child when you watch something – completely open, forgetful of yourself and present. That gets harder when you’re familiar with how the illusion has been made. Having said that, I’m still amazed and thrilled by how often it does still happen to me in theatres, cinemas and in front of the TV. But I guess I love books best now because I don’t have any understanding of how their magic works – and dance too. That’s another thing I’d love to have been, a dancer.

Q: There’s a familiar question that always comes up in adaptations of Shakespeare, namely how to make a shared cultural icon relevant to a broad modern audience. In the case of your recent role as Richard II, did the medium of television change your approach in any way?

BW: The play Richard II is written entirely in verse - the only one in the whole canon. It has formality and ceremony and ritual. But there’s so much happening underneath the words and the pomp; so much that’s unspoken. We could really explore that on television. I think television is so humble and accessible – it’s great for Shakespeare because I sense that a lot of people feel Shakespeare isn’t for them, that they won’t understand it and would never pay to go and see it in the theatre. It was a joy to put these words from 400 years ago in people’s front rooms.

Q: Your break came playing Hamlet in 2004; a role described as a hoop through which every actor should jump. Since then you have conquered a long list of eminent male characters including Bob Dylan and John Keats. For which role did you find the research most rewarding?

BW: Research is a strange thing to me because sometimes it seems very important and at other times I’ve had the feeling that I don’t need or want to research anything at all. I loved researching John Keats - I loved having an excuse to sit and read those poems for weeks on end - especially some of the longer and odder and less perfect ones like ‘Endymion’ that you might normally pass over. His letters are incredibly beautiful – so intimate and wise. I also loved reading about the real King Richard II, that research definitely helped me understand better what Shakespeare was writing about. For Cloud Atlas I had to learn to play the piano which was great. Other times however, I don’t do much at all – consciously. I go on some instinct I have.

Q: With both Dylan and Keats, you have spoken of the intense personal connection you developed while researching each role, something almost akin to love. Yet you’ve also spoken of the ease at which you discard them. Is that a conscious choice?

BW: I love all the characters I play. I’m fascinated by them. It’s like you’re looking after someone else’s existence for a while. Quite a responsibility. But once the experience is over it’s important for me to drop it and get on with a new project and my life. Also, I have quite a poor memory.

Q: Shall we test that out? Complete the line: “A thing of beauty is a joy for ever…”

BW: “Its loveliness increases…” um... then something like “it will never fade into nothingness...but will keep a bower safe for us…” Oh dear – see I’m not very good.

Q: One of your latest roles is Q in the new James Bond, a character totally associated with Desmond Llewelyn. How did inheriting a role change your approach?

BW: I was quite nervous. In a way though it’s a bit like doing a Shakespeare role that’s already been inhabited by many other actors. I’m quite used to that feeling now. I try not to let it weigh on me much and just play the character as I see it.

Q: Many actors cite a particular change in appearance, for example a wig or costume change that signifies the beginning of their playing a character. Is the external changing of your appearance, with costume and make-up an important role in developing a character?

BW: I love the element of acting that’s dressing up – yes. That’s where it all stems from I think - the child’s dressing up box - it’s playing. I love how wearing someone else’s clothes can make you feel different, move differently, even think differently. I’m always clear in my head that the character I’m playing is very distinct from me and at the same time so much of you ends up leaking into the character. It’s an odd business.

Q: In a very different way, the challenging narrative of this year’s sci-fi epic Cloud Atlas, based on David Mitchell’s novel of the same name, presumably presents some new scope for experimenting with how you connect with your character. Rumour has it that the actors will be playing multiple roles that span gender, time and even ethnicity. Can you talk a little about how this experience differed from your previous roles? Did you enjoy it?

BW: Cloud Atlas really was the ultimate dressing up experience. It was massive fun. There were wigs and there were prosthetics. I play a 56-year-old woman at one point – Hugh Grant’s character’s wife. I also have a tiny walk on part as a Korean businessman. That was hilarious. I played six characters in all; one in each of the stories. I was only originally going to be in three, but it became a bit of a competition between the actors to see who could get into all the stories. There were three directors too. It was all incredibly ego-less, in a way. A massive experiment. Very special to be a part of. I’m so eager to see it.

Q: You are soon starring in John Logan’s Peter and Alice with Judi Dench, a play based on an encounter between the real-life figures behind Lewis Carroll’s Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland. Michael Grandage has suggested that it focuses on “iconic figures coping with their own reality”. Did you draw on any personal preoccupations with the themes of privacy and celebrity?

BW: I’m very excited about that play! I’ve had a photo by Lewis Carroll that I found in a junk shop hanging on my kitchen wall for years - it’s a portrait of the little girl who inspired Carroll to create Alice in Wonderland. The play is about so many things, but yes it touches on celebrity and privacy and identity. Earlier in the summer I went to see the Pina Bausch ‘World Cities’ series and I became friends with some of the dancers from the company. We talked about how the dancers don’t even have their biographies in the programme or anything. I said that that’s never the case for actors. You always have to reveal something. But it’s a shame I think. For me it’s best when I know nothing, when there’s nothing in the way of the people on the stage or screen in front of me. Then you can project your dreams and fantasies onto them.

This article first ran in Fourth & Main ( www.fourthandmain.com) Journal Vol. 2

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments