We were all complicit in what happened to Monica Lewinsky after the Clinton affair

As ‘American Crime Story’ prepares to tackle the 1998 White House scandal, Fiona Sturges asks why we laughed when a 22-year-old intern was so viciously hung out to dry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I remember how we laughed at the time. I remember how we gasped and giggled at the tawdriness of it all, and how, in lapping up the headlines, we were complicit in a vulnerable young woman’s agony. I remember, and it makes me flinch with shame.

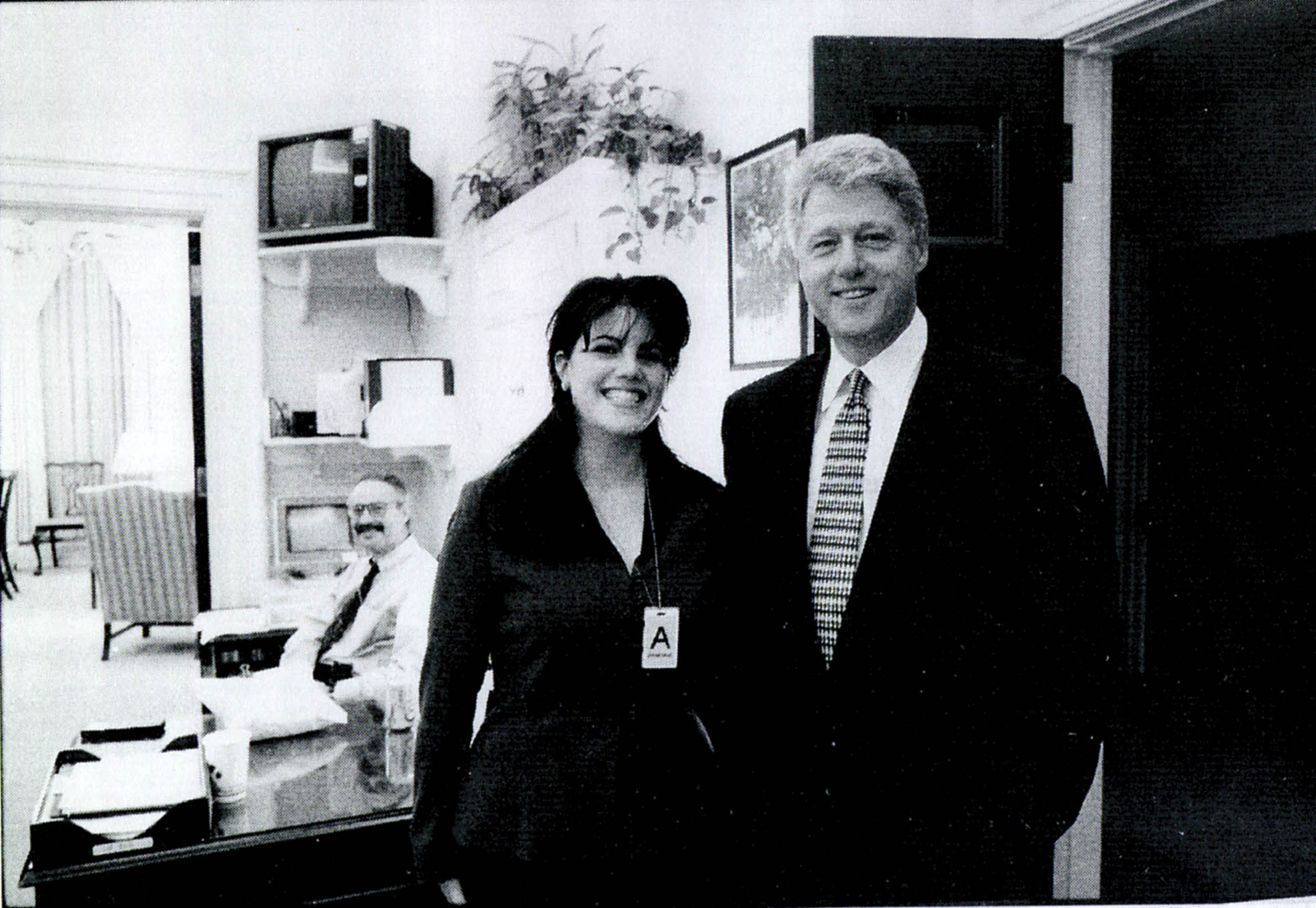

When, in 1998, news of the US president Bill Clinton’s affair with a 22-year-old intern named Monica Lewinsky broke – the affair over which he lied, and called her “that woman”, and lied some more – the world couldn’t get enough of it. It was the ultimate potboiler played out in the news – a tale of sex, betrayal, conspiracy and a blue dress with an incriminating stain. It nearly derailed a presidency, which was a big deal, but the fact that it destroyed a young woman’s life barely registered. Lewinsky was vilified by the press, betrayed by her friends and, it transpired, threatened with 27 years in jail in a terrifying FBI sting. Hell of a story though, huh?

Two decades on, we are older, wiser and more alert to the toxicity of public shaming. #MeToo has given us pause, both to recalibrate our own experiences with men in positions of power, and to look again at those of others. Hollywood has been doing some recalibrating of its own, not just about how it looked the other way with Harvey Weinstein, but about the stories it tells. This week has brought news that the next instalment of American Crime Story, the critically adored anthology drama that has so far brought us fictionalised accounts of the murder of Gianni Versace and the OJ Simpson trial, will tackle the Clinton-Lewinsky affair and subsequent impeachment proceedings. Crucially, the series, adapted by Ryan Murphy from Jeffrey Toobin’s book A Vast Conspiracy: The Real Story of the Sex Scandal That Nearly Brought Down a President, will have Lewinsky as executive producer. Lewinsky told Vanity Fair that she had been hesitant to involve herself with the series but that she was swayed by the opportunity to “reclaim my narrative”.

Going on the quality of the series’ predecessors, I’d say all this seems like good news. Also cheering is the fact that Murphy optioned the book in 2017 but declined to bring it to TV without Lewinsky on board. As he explained to The Hollywood Reporter last year, “I told her, ‘Nobody should tell your story but you, and it’s kind of gross if they do… You should be the producer and you should make all the goddamn money’.” But the question remains: how has it taken over 20 years for Lewinsky to be able to trust others to portray her respectfully, and to be viewed as the victim that she was all along?

In 2015 Lewinsky delivered a simultaneously heartbreaking and electrifying TED talk about being the first casualty of mass internet shaming. “Overnight, I went from being a completely private figure to a publicly humiliated one worldwide…” she said. “I was branded as a tramp, tart, slut, whore, bimbo and, of course, ‘that woman’. It was easy to forget that ‘that woman’ was dimensional, had a soul, and was once unbroken.”

Since then, conversations about sex and power have become louder. In prompting women to open up about their trauma, #MeToo has yielded a greater understanding of the patriarchal structures that remove agency from women and allow men to maintain their positions despite their misdeeds. Scriptwriters and directors have woken up to these conversations too. This spring, Emily Nussbaum of The New Yorker hailed “a deluge of TV series that feel like a direct response to the #MeToo movement, touching on third-rail themes that are meant not merely to comfort or inspire but unsettle”. Among the shows exemplifying this changing landscape, said Nussbaum, were The Bold Type, about three young women starting out in journalism, Fosse/Verdon, documenting the troubled relationship between the choreographer Bob Fosse and the dancer Gwen Verdon, and the animated comedy series Tuca and Bertie (which has since been cancelled).

This all sounds heartening until you consider that the fastest growing genre now is true crime, specifically dramatised whodunnits and documentary investigations in which men are the charismatic killers and women are their mute victims. This year we have seen the former Disney heartthrob Zac Efron charming women into an early grave as Ted Bundy in the archly titled Extremely Wicked, Shocking Evil and Vile, and the release of the documentary, Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, in which we heard Bundy prattling pointlessly about his innocence. Currently in cinemas is Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, about Charles Manson, and in which Margot Robbie, playing Manson’s best-known victim Sharon Tate, flutters around looking beautiful while saying almost nothing. Meanwhile, men still outnumber women when it comes to writing and directing films – see this year’s Cannes Film Festival, which featured only four female directors in the main category, out of 19 entries.

Change happens slowly. Despite good intentions, and endless rallying statements, male stories, and the male gaze, still dominate film and TV. It’s no wonder that Lewinsky has hesitated in telling her own story – life has shown her that the world cannot be trusted to treat her with dignity and that a powerful man will do and say anything to preserve the status quo. The shame is ours, not hers. It’s time to make things right.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments