‘The true crime story that keeps on giving’: Why we can’t get enough of Kim Philby and the Cambridge spies

As Damian Lewis and Guy Pearce star in the ITVX drama ‘A Spy Among Friends’, Katie Rosseinsky talks to its screenwriter and others about our enduring fascination with the double agents who met at university in the 1930s

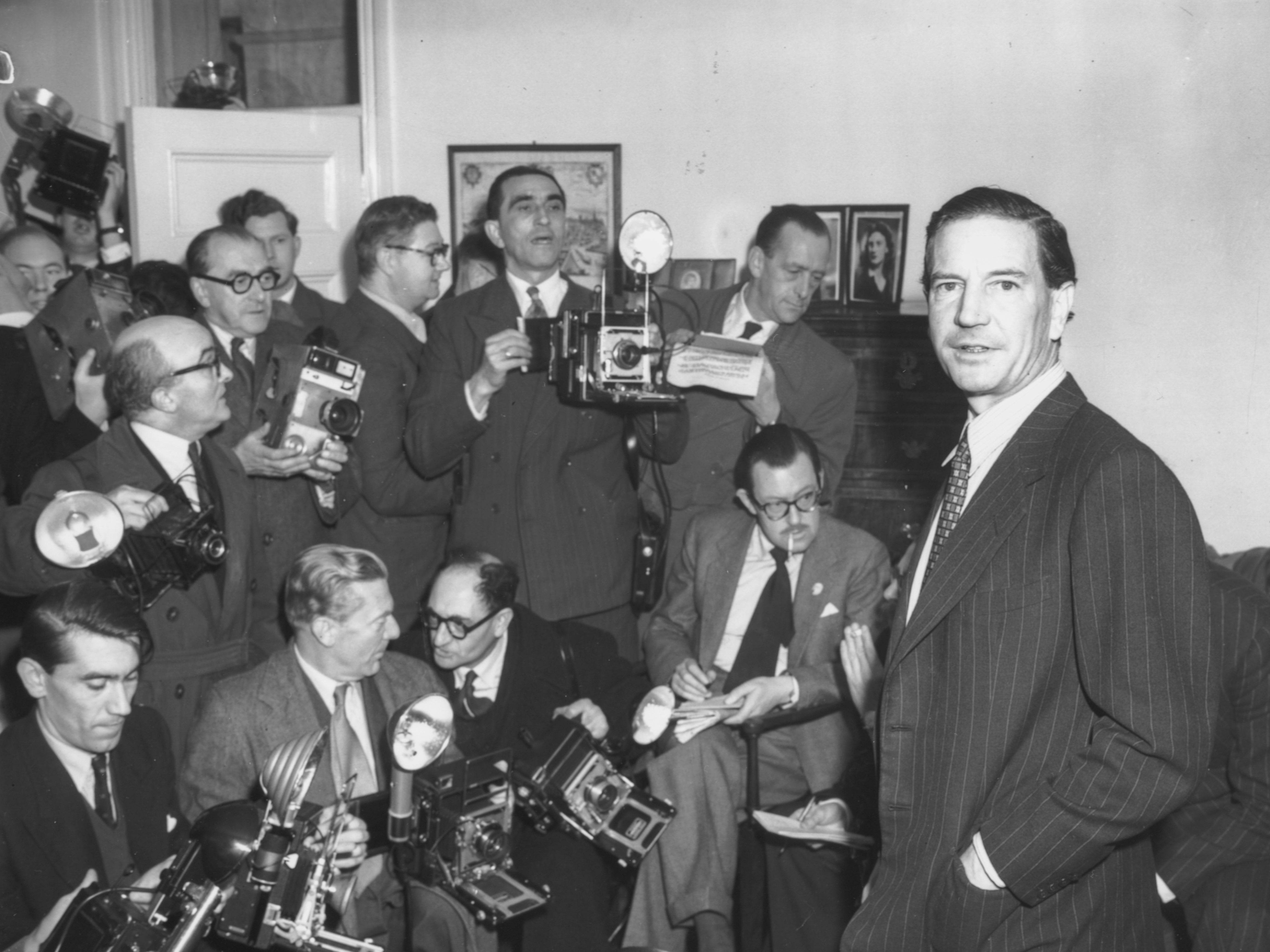

On 9 November 1955, the world’s media crowded into a fourth-floor flat in South Kensington in London, their cameras trained on a self-assured man in his forties, speaking with the clipped accent and unshakeable confidence that is drilled into a certain class of British male through years of expensive schooling. He answers the questions posed by his American interviewer with few words, sometimes accompanied by the flicker of a smile, a slight air of ennui, as if he is bored with the whole charade.

His name is Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known to his friends, and now the world, as Kim. The interviewer asks whether Philby is satisfied with his newly clean reputation, now that he has been ruled out as “the so-called third man” – the mole thought to have tipped off British agents-turned-Soviet spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, allowing the pair to defect to the USSR in 1951. After Philby gives a brief assent, his questioner pushes a little further. “And if there was a third man, were you in fact that third man?” he asks. “No, I was not,” comes Philby’s reply, followed by another half-swallowed smile.

Nearly 70 years on, the black-and-white Pathé footage from the press conference in Philby’s mother’s flat still makes for astonishing viewing. Philby was lying through his teeth, but he certainly gave a consummate performance – just as he had done for the past three decades, working as a Soviet Russian mole within the upper echelons of MI6, while seeming to embody the image of a very British gentleman.

The scene is recreated in the opening episode of ITVX’s new drama A Spy Among Friends. An adaptation of historian Ben Macintyre’s 2014 book, it stars Guy Pearce as Philby, and explores the infamous double agent’s betrayal through the prism of his friendship with fellow operative Nicholas Elliott, played by Damian Lewis. “Damian often refers to the relationship between Philby and Elliot as an adulterous marriage,” says the show’s screenwriter Alexander Cary – with Russia as the third party.

It was Elliott, Philby’s long-time colleague and drinking buddy, who was eventually entrusted with extracting the truth from him in Beirut (where Philby was working as a journalist for the likes of The Observer and The Economist after being ousted from MI6). Philby’s confession was made over cups of tea, in between chatter about cricket scores – a very British verbal sparring match. Weeks later, Philby defected to the Soviet Union, smuggled aboard a freighter ship; there, he was kept under virtual house arrest, writing his memoirs and knocking back vodka. Whether Elliott accidentally-on-purpose let his old pal slip away has long been debated, and in A Spy Among Friends, Anna Maxwell Martin’s MI5 agent Lily Thomas (a character invented by Cary) must unpick his motives in a series of interrogations.

Philby and the Cambridge spy ring – which also included Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross, along with Burgess and Maclean – have fascinated the British public for decades. A Spy Among Friends is the latest in a long line of TV series to grapple with this intriguing episode in British history. In the years since Burgess and Maclean’s defection, this tale has become embedded within our cultural landscape, echoing through spy stories on TV from the classic Seventies adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy to Bodyguard: if you’ve ever watched an espionage drama where a top spy boss is unmasked as the traitor within, then you’ve felt their influence.

It crops up in projects as seemingly disparate as The Crown (which focuses on the Queen’s relationship with Blunt, who worked as the Surveyor of the King’s and later the Queen’s Pictures from 1945 to 1972) and The Imitation Game, where Benedict Cumberbatch’s codebreaker Alan Turing works alongside John Cairncross, the Bletchley Park cryptanalysist who would be unveiled as the “fifth man” in the Cambridge ring in the Nineties, decades after his fellow spies.

The paradox of secrecy drives our interest in spy stories – we crave access to things we’re not allowed to know, and want to enter the places from which we’re prohibited. “The more you try to keep something quiet, the more interest it is going to attract,” notes Dr Christopher Murphy, lecturer in intelligence studies at the University of Salford.

The Cambridge spy ring saga takes us into the heart of two rarefied institutions – the secret service and high society. And it’s precisely because of this overlap, between the spy world and the upper social strata, that many of the details were hushed up for so long. “Archival material” on these double agents has been released “through gritted teeth, materials have become available with the authorities sort of kicking and screaming to try and keep it quiet”, Murphy adds. But this “reluctance for the authorities to tell […] an uncomfortable story”, he says, has created a “drip feed effect” that has kept the spies in the public consciousness for longer.

Philby was nicknamed “Kim” by his father, in a nod to the Rudyard Kipling poem which, in an uncanny coincidence, is a very English story of duality, all about a boy spy who becomes “a two-sided man”. Like Burgess, Blunt, Maclean and Cairncross, Philby encountered communist ideas at Cambridge. The establishment bastion was an unlikely hothouse for radical politics – Philby would later recall asking his economics lecturer Maurice Dobb, an avowed Marxist, how he might “devote his life to the communist cause” after graduating.

The ideological Cold War clash of communism versus capitalism makes an irresistible backdrop from our modern vantage point. “There’s a nostalgia for a time when the big intelligence conflicts felt like they were about ideals,” says Dr Joseph Oldham, lecturer in communication and mass media at the British University in Egypt and author of Paranoid Visions: Spies, Conspiracies and the Secret State in British Television Drama. “It’s very disputed as to what motivated the Cambridge spies, but [they were] people who were potentially motivated by grand ideals of an alternative society – lots of tensions nowadays are compared to the Cold War, but it’s not really [the same as] that fundamental challenge of ideology”.

When the screenwriter Peter Moffat made the 2003 series Cambridge Spies, he doubled down on this idealism to dream up a glossy, glamorous story of “four very British traitors”, as the text that opens each episode puts it (his show largely skips over Cairncross), heavily indebted to Brideshead Revisited. It’s a deeply sympathetic portrayal, complete with some very flattering casting decisions. “It really hammers home the idea that their initial motivation is to fight fascism,” Oldham says. “Which is, in many ways, the easiest way to give them a more sympathetic spin.”

In Moffat’s reimagining, Burgess gives impassioned speeches about starving children, Philby leads a workers’ uprising in the dining hall of his college and both stand up for Jewish students: they become, as the TV critic Mark Lawson put it for The Guardian, “the pro-semitic heroes of organised labour”. No wonder the show’s quasi-heroic framing of some of Britain’s most notorious traitors provoked a Crown-style controversy over the ethics of blending fact and fiction.

On a trip to Vienna in 1934, Philby would meet and fall in love with an Austrian communist activist, Litzi Friedmann; a friend of hers, Flora Solomon, later introduced him to a man known as “Otto”, aka Arnold Deutsch. Under the guise of studying for a PhD in phonetics and psychology at University College London, Deutsch was working as a recruiter for the NKVD, the Soviet secret police agency which was a forerunner of the KGB. They were playing a long game: Deutsch’s brief was to talent spot bright young radicals who might rise to prominent positions in years to come.

Accounts of precisely who recruited who vary, but Burgess, Blunt, Maclean and Cairncross were soon spying too – and within a few years, all of them were working within the heart of the British establishment: Philby and Cairncross at MI6, Blunt at MI5, Maclean at the Foreign Office, and Burgess at the BBC, then MI6, then the Foreign Office.

How did a group of men who never tried to hide the political leanings of their youth end up walking into roles as spies and diplomats, at a time when communism was a political bogeyman? There was no vetting process; entry to the service came through a tap on the shoulder – in a gentleman’s club, around the dining table in a country home or, for Elliott, at Ascot races. If you were the right sort of English chap, you were in. In his book, Macintyre recalls how the deputy head of MI6, Valentine Vivian, was asked to provide references (of a sort) for Philby. “I said I knew his people,” were his magic words.

I was at private schools and I do remember thinking, ‘Oh, these people actually think that we are the future of the country, they actually believe that’

Cairncross was the only outlier. He had attended Cambridge on a scholarship and lacked the other spies’ privilege. Their status as expensively educated men who knew the right people didn’t just open doors: it would later protect them from suspicion. Their peers would find it impossible to believe that one of their own could possibly be a wrong ’un. Treachery was for other countries.

There’s an exquisite irony in the English obsession with class facilitating a great betrayal of England – a very British undoing. There’s also, Cary says, a particularly British “eccentricity” to this rationale, and an “arrogance, particularly when it’s framed in the English public school culture… I was at private schools and I do remember thinking, ‘Oh, these people actually think that we are the future of the country, they actually believe that.’” Maxwell Martin’s character, he explains, was intended as “somebody who is a complete affront to the old school tie [culture], deliberately sent in there by MI5, to piss them off”.

Philby rose the highest in the secret service, eventually becoming first secretary to the British Embassy in Washington and working closely with CIA counterintelligence boss James Jesus Angleton. The further he and his co-conspirators climbed, the better the material they could pass on to the Soviets. According to Macintyre’s book, the Russians were often deeply suspicious of intelligence passed on by the Cambridge spies – it seemed too good to be true. Perhaps, some KGB operatives wondered, they could actually be triple agents?

Things started to fall apart in the early Fifties, when US and UK codebreakers managed to decode a cache of Soviet messages in an operation known as the VENONA project. One of these missives described a Russian spy meeting a double agent in Washington; the agent would soon be visiting his pregnant wife in New York. When Philby gained access to VENONA material, he learned that Maclean (whose wife Melinda was indeed staying with her American family while expecting their first child) was at risk.

He and Burgess, by this point a barely functioning alcoholic, cooked up a scheme to get the latter sent home (by racking up three speeding tickets in one day) where he could alert Maclean. After Burgess made the decision to flee to Moscow with Maclean, Philby was questioned about his involvement, and was able to convince his colleagues of his innocence – but didn’t manage to stay in his job (he received a generous £4,000 pay-out in lieu of a government pension). It was not until 1961 that MI6 had to face up to the truth: Soviet spy Anatoliy Golitsyn had defected to the West, bringing with him intel on the moles inside the American and British secret services. Elliott was sent to Beirut to extract a confession from his friend. “I rather thought it would be you” was Philby’s melodramatic response on opening the door to his friend.

Indeed, the Cambridge spy tale has “got all the elements of a soap opera”, as Murphy puts it. With its blend of personal and public betrayals, its moral panic (the press kept returning to Philby’s philandering, and Burgess and Blunt’s homosexuality) and its readily available symbolism (both The Crown’s Peter Morgan and Alan Bennett, in his play-turned-TV-film A Question of Attribution, used portraits within portraits, faces “lurking beneath the surface”, when grappling with Blunt’s duplicity), it’s perfect raw material for a screenwriter – a stranger than fiction story that would seem far-fetched if it was made up.

There has, Murphy says, always been a “strange interplay of fact and fiction… within the history of the British intelligence community”, with former agents like Ian Fleming (who crops up as a character in A Spy Among Friends) and Graham Greene (who briefly reported to Philby while working for MI6 and would become one of his few public defenders) later writing stories that would shape the portrayal of spies on screen. It was John le Carré, though, who would create the most enduring re-workings of the Cambridge spy case. Though he never met Philby, he blamed him “for leaking information that betrayed him to the Soviets” and ending his own career as a spy, Oldham says (though he notes that Le Carré’s biographer Adam Sisman has disputed this claim). Le Carré’s eldest son, Simon Cornwell, has since confirmed that his father “wouldn’t have been blown by Philby because he was already blown by [the MI6 officer and spy] George Blake”.

The writer would eventually become “really interested in the close biographical similarities” between himself and Philby, Oldham adds, as “both had enormously domineering fathers they were seeking to fight back against”. Le Carré would go on to fuse elements of his own backstory with Philby’s to create the fictional double agent Magnus Pym in his 1986 novel A Perfect Spy, later adapted for the BBC (in his 2008 interview with Le Carré for the Sunday Times, journalist Rod Liddle claimed the author had admitted to being “tempted” to spy for the Soviets; Le Carré later wrote a denial to the paper saying that the pair had been “sipping post-prandial Calvados” and Liddle “made no visible use of a tape recorder”).

Released in 1974, Tinker Tailor Solder Spy is probably Le Carré’s defining work. It follows the semi-retired George Smiley as he attempts to identify the “mole” at the heart of Cambridge Circus (his fictional MI6 HQ), eventually unmasking deputy intelligence chief Bill Haydon as the traitor. His detective work, Oldham notes, “doesn’t map very closely” onto the hunt for the real-life double agents, but Haydon, aristocratic, charming, promiscuous, certainly has shades of Philby.

The BBC’s 1979 adaptation of Tinker Tailor luxuriated in the ambiguities of Le Carré’s story over the course of seven episodes. It also set the blueprint for a very different sort of spy series: with its long, wordy interrogation scenes, a slow, deliberate pacing that prioritised simmering unease over action sequences, and labyrinthine twists and turns, it made the antics on display in espionage shows like The Man from UNCLE and The Avengers seem seriously cheesy.

Drawing in an average of 8.5 million viewers, it became such a talking point that Terry Wogan’s Radio 2 breakfast show ran a segment asking, “does anyone know what’s going on?”, while the Radio Times printed a glossary for its incomprehensible terms like “scalp hunters” and “lamplighters”. And, in another jaw-dropping twist, just a few weeks after Haydon was unmasked on screen, the news of Anthony Blunt’s treachery hit the headlines. Imagine the media storm if a top police boss had been revealed as a “bent copper” just after Line of Duty’s finale and you have an idea of the impact.

Part of the reason why the Cambridge spies continue to captivate us, Oldham suggests, stems from “a nostalgia for a time when intelligence work felt more human – it wasn’t filtered through technology so much”. A Spy Among Friends certainly revels in taking us back to that era of dead letter boxes, rendezvous in smoke-filled dodgy pubs and old school spy craft (a contrast to the tech-focused plots of recent small-screen thrillers like The Undeclared War and the Slow Horses series) but it explores perennially troubling questions about human nature too: how much can we ever really know the people who are closest to us?

“How genuine was that friendship?” Cary asks. “It’s really weird to be betraying someone for 23 years, throughout the entirety of their friendship, but [at the same time] the friendship seems incredibly real and seems to mean a great deal to him. So how does and how can that work?” Philby, it seems, could value and respect Elliott while passing reports on him to the Soviets (one of which described him as “ugly and rather pig-like to look at. Good brain, good sense of humour”). Elliott, meanwhile, would later despise Philby’s treachery, while mourning the gap left in his life by his absconded friend. It’s that impenetrable and very human tangle of motives and loyalties that makes the Cambridge spies, as Cary says, “the true crime story that keeps on giving – there’s never really a verdict”.

‘A Spy Among Friends’ is on ITVX from 8 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks